“To be creative you’ve got to be unsociable and tight-assed. Not necessarily violent and ugly, just unfriendly and distracted,” Bob Dylan told me last month. “You’re self-sufficient and you stay focused.”

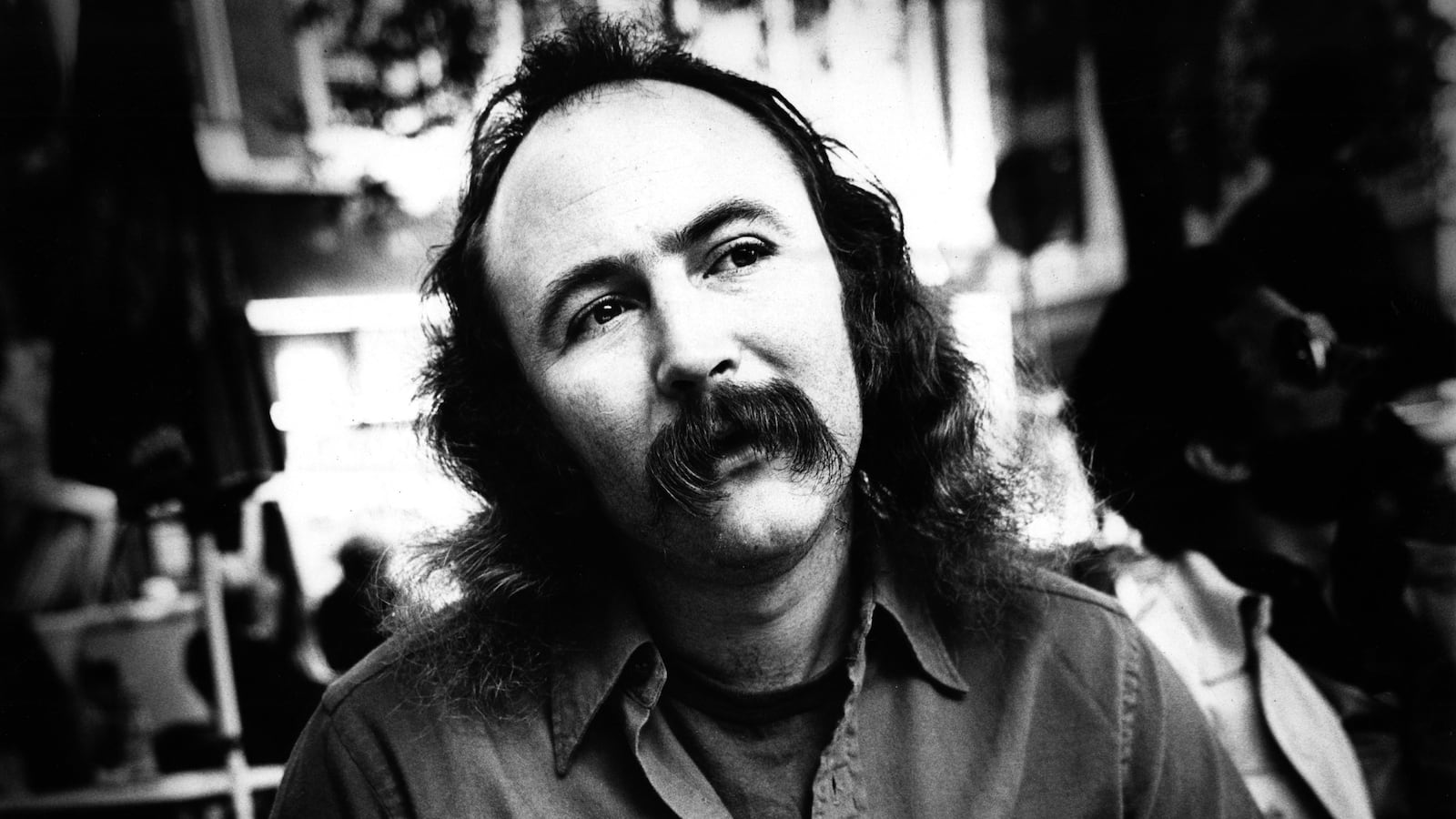

That was David Crosby, who died on Thursday at 81, after a lifetime in search of not fame and fortune, but exactly that elusive creative spark Dylan spoke about.

In the wake of his passing, Crosby is being remembered as many things—legend, iconoclast, Boomer icon, curmudgeon, and even asshole—all of which underscore precisely the life path he chose: one of a true creator and collaborator, rather than some mere mortal. Freak flags, as one writer put it, are flying at half-staff. It’s all fitting and beautiful (even the asshole part), and would no doubt make the typically effervescent Crosby laugh that high, cackling laugh that was so singularly his.

I first crossed paths with Crosby after a show by Crosby, Stills & Nash, the group he co-founded that also occasionally included Neil Young, more than 30 years ago. The show was, to put it bluntly, less than stellar. But Crosby had already lived several lifetimes by then—creative, sure, but also wild, hedonistic, and, often, seemingly cursed. He’d topped the charts with The Byrds and CSNY, and played Woodstock and toured stadiums at a time when that was unheard of. But he’d also more than once been the reason his groups had crashed and burned, buried a soulmate, overdosed countless times, and done hard time in jail, creating the template, for good and bad, of what would come later in rock ‘n’ roll.

But I really got to know Crosby beginning about a decade ago, when I interviewed him about the then-new box set chronicling CSNY’s 1974 mega-tour. When he greeted me at his hotel room door, he looked me up and down, squinted his eyes, then smiled and said, “You’re no reporter. You’re one of us, man!”

I explained that I was indeed a musician, but with the days of being able to do that, and that alone, long over, I had turned my hand to writing about what I loved.

“Tell me about it, man,” he exclaimed, visibly angry at the idea of not being able to make a living at music. “These are dark times.”

He invited me in, before rushing to his laptop to finish his latest Twitter brawl—something he loved doing almost as much as making music. I’d been promised 20 minutes with Crosby, but over three hours later, with him already late for soundcheck for his show at New York’s Beacon Theater that night, we were still at it. We’d discussed his seminal albums with The Byrds at length. (His favorite was 1967’s Younger Than Yesterday. “That was when we came of age,” he said.) We also discussed his 1988 memoir, Long Time Gone, his problems with addiction, his rocky relationships with his various bandmates, and, much to his enjoyment, the new music he was making, which he played rough mixes of from his laptop. But with the clock ticking, I began to pack up.

“Hey, man, are you coming to the show tonight?” he asked as I headed for the door. Then he caught himself.

“You know, you barely asked about CSNY,” he said.

I told him I wasn’t really a fan; that I’d grown up on punk and old-school soul, and that, while I loved some of the music, I also saw the group as the progenitors of a darker side of the music industry, one that culminated in the “profits over art” sensibility of The Eagles.

He squinted hard at me. For a second, I thought Crosby might take a swing at me; his reputation as being hot-tempered, of course, long preceded him. But then he let out a long, loud laugh.

“I get it, man,” he said, with a broad smile on his face. “Let’s continue this soon. I think we have more to talk about.”

I knew I’d made a friend, and I wasn’t wrong. Over the next decade, I interviewed Crosby several times. He was boisterous and opinionated, sure, but he never put on airs; never played the game of a rock star promoting his latest project. He always said what was on his mind—how Trump was a buffoon, Kanye was a pretender, Jim Morrison “just plain sucked”—but in a way that was so forthright and refreshing that, even when we disagreed and battled it out, I found Crosby nothing short of endearing and totally engaged.

This was all during a career renaissance for him. While his peers took endless victory laps, Crosby, never known as a songwriter, released a batch of new albums that stood with the highest heights of his Byrds and CSNY days. In fact, 2021’s For Free, Crosby’s most recent studio album, and the live album and concert film with his Lighthouse Band, Live at the Capitol Theater, from last year, continued a hot streak that began with Croz in 2014 and continued through Lighthouse (2016), Sky Trails (2017), and Here If You Listen (2018). Perhaps more often sounding like his beloved Steely Dan than CSNY, Crosby’s recent work offered up songs that were more varied, wizened, and elegant than even his best-known work. More than that, he seemed to be having a better time doing it than at any time in a career that can only be referred to as both genre-shaping and tumultuous.

He was buoyed by the reception to his recent recordings, as his solo work had often been dismissed (with the possible exception of 1971’s If I Could Only Remember My Name, which has long been a favorite of indie and Americana artists). A bit atypically humble about it all, Crosby chalked it up to the skill he felt had truly marked his career: his ability to collaborate.

“It’s something I have an ability for,” he explained when we spoke in 2021. “It’s something I have a spotter for. I can see a chemistry when it’s happening. I know when there’s a chemistry going on. I have an antenna that just receives that, really large. And when I get a shot at doing it with somebody that can do it, I treasure it, work at it, try to make friends with them, and try to be available every way able to help make it happen with them. Because it’s like two painters: If you have seven colors on your palette and then you partner up with somebody who has seven other colors, then you’ve got 14 colors. It’s going to be a better painting. The person will always think of something you didn’t. And therefore, there’s more depth, more spread, more ideas, more construct, more everything.”

After that initial encounter, Crosby and I stayed connected off the record. We texted and chatted about everything from his love of Joni Mitchell to political injustices to the latest music industry gossip. He often bemoaned the fact that he couldn’t foresee a creative reconciliation with his “musical brothers” Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman of The Byrds, whom he loved dearly.

“I don’t think a rapprochement is ever going to be there, man,” he told me in 2021, clearly brokenhearted at the thought. “I’ve asked those guys to sing with me repeatedly and they always turn me down. I’ve asked them probably 10 times. And they’ve always said no.”

He was less troubled by his irreconcilable differences with Neil Young, Stephen Stills, and, especially, Graham Nash that had recently played out in the press.

“It petered out,” he said in 2017, plainly. “I mean, what’s the last CSN record you think was great? But if Neil comes and says, ‘10 million dollars a guy, I need two months.’ Fine. I can pay my house off. I’ll do it. I’m a grown-up. I understand what’s at stake. But there’s just no joy there.”

Still, in our many conversations, he expressed nothing but respect for Young, and never missed an opportunity to rave about Stills’ musicianship and skill at making great records. He had no time for Nash, though. The man who, from outside appearances, had stood by Crosby during his darkest times was barely worth mentioning.

“That’s because he comes from a different place, man,” Crosby said, bitterness in his rising voice. “He was in a pop band, so that’s really where his orientation is: to be a successful, important world pop star. I love that guy, but his book is where things went awry. It was a remarkably dishonest book. He made himself out to look fantastic, but whenever he needed … something wild to move the story forward, he used my stories. It wasn’t cool. It just wasn’t OK; and all that stuff is already known, anyway. But he did it from a different point of view, where he added everything to make him look terrific and me look bad.”

But, again, that was Crosby. He felt wronged, he had the receipts, and he wasn’t going to just let it go or say nothing. Whether on the record or off, he never missed a chance to rail against injustice. From Nash to the “greedy bastards” at Spotify to his ever-present punching bag Trump, I always knew where Croz—as anyone who knew him even a little bit called him—stood.

“I know I’m at the end of my life,” he told me in 2021. “So you wind up looking at it, and you don’t know whether you got two weeks or 10 years. You really don’t. But you do know that what you do with the time is what counts. That’s where the rubber meets the road. How do you spend that time? You spend it waiting to die? No. You spend it making the most art you possibly can, because that’s your gig and that’s the one contribution you can make to the world. And the world fucking needs it. It’s a grim fucking place. It needs a lift, and music is a lifting force, man. It makes things better. So whatever time I’ve got, I want to spend it making things better. I want to spend it making good art that will outlast me.”

And that he did.

“Crosby was a colorful and unpredictable character, wore a Mandrake the Magician cape, didn’t get along with too many people and had a beautiful voice—an architect of harmony,” Dylan wrote about Crosby in his 2004 book Chronicles: Volume One. “He could freak out a whole city block all by himself. I liked him a lot.”

I did, too. Rest easy, David. Fly high.