When he announced the opening of an impeachment inquiry on President Joe Biden, Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) carefully avoided suggesting that House Republicans would inevitably reach the outcome many of his members are craving.

“We are committed to getting the answers for the American public—nothing more, nothing less,” McCarthy said during brief remarks on Tuesday. “We will go wherever the evidence takes us.”

But to many lawmakers, including some Republicans, it’s fairly obvious McCarthy will end up where the politics takes him: a full vote to impeach the president.

“When he used the term impeachment inquiry… now we have set expectations with the activists who are expecting an impeachment,” said Rep. Ken Buck (R-CO), a conservative who has been skeptical of the push. “When you start talking about the I word, the activists get fired up.”

“It doesn’t matter what the facts are,” Buck said. “They want us to move forward.”

In addition to the party base, the hard-right lawmakers who are threatening to tank federal spending bills ahead of a Sep. 30 shutdown deadline—and also happen to be threatening to end McCarthy’s speakership—have long clamored to impeach Biden, not merely to consider impeaching him.

It’s unlikely these lawmakers, some of whom use phrases like the “Biden Crime Family” and loosely insist the president is guilty of criminal conduct, will be satisfied with an impeachment inquiry that does not result in an impeachment vote. In fact, starting an inquiry and not ultimately impeaching Biden may give the appearance that Republicans are actually acquitting the president.

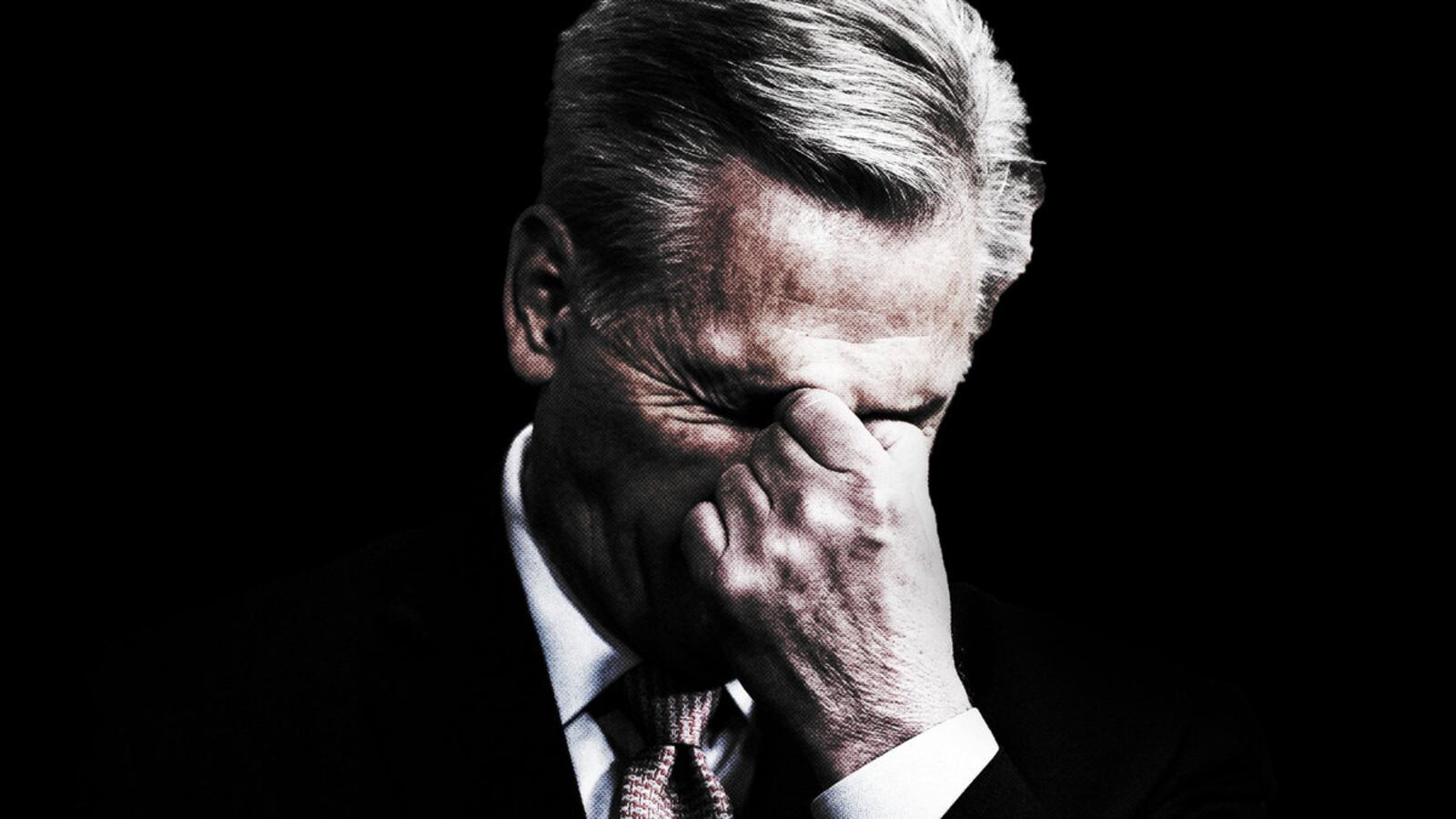

Through nine months, McCarthy’s speakership has offered little evidence to suggest he would be able or willing to resist far-right pressure to go after Biden. McCarthy’s survival has defied expectations, but he has made it through each day by making whatever political bargains and concessions necessary, usually to placate the most extreme wing of his conference.

The impeachment announcement, said Rep. Jared Huffman (D-CA), is “obviously a protection payment to the mob, that enables McCarthy to hold the gavel. It’s nothing more than that.”

Huffman expressed doubt that Republicans would even go through with an impeachment vote, or Senate trial, given the evidence. “I’ll be surprised if they can even get to that,” he said. “Even if they do, it’s a national joke, and everyone knows it.”

But McCarthy is “under a lot of pressure to act, both inside and outside pressure,” said Buck, leading to the congressman’s concern that the impeachment effort will gain momentum—regardless of what facts are, or are not, unearthed.

The politically dangerous impeachment quest could, at last, represent a bargain that McCarthy cannot afford. Buck argued the decision to move forward with the inquiry—without holding a full floor vote to authorize it—amounted to a major “self-inflicted wound” for the Speaker.

“He’s the one that raised the issue of impeachment. Everybody on the outside wants to talk about it, let them talk about it—we have an institution and we have to keep it moving,” the Colorado Republican said. “How do you go to Democrats and say, ‘I need your vote on the [continuing government funding resolution],’ right after I’ve said, ‘I’m going to beat your president?’ It’s crazy.”

The deep irony of the GOP’s impeachment push is that McCarthy and Republicans themselves made many of the arguments against Democrats in Trump’s first impeachment that they are fielding now.

In 2019, when then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi opened an impeachment inquiry into Trump for pressuring Ukraine’s president to dig up dirt on Biden, Republicans slammed it as a formality to satisfy Democrats’ zeal to impeach Trump.

Pelosi also launched the inquiry without a vote, which McCarthy and the Trump administration argued made the exercise illegitimate. Four years later, McCarthy has done the same thing, despite vowing to hold a vote first. He has since claimed he is merely following the precedent set by Pelosi.

Both party leaders lacked the necessary votes to formalize an impeachment inquiry at the start. But in Trump’s so-called “perfect call” with President Volodymyr Zelensky, Democrats had a clear action to build an investigation around.

For most of this year, Republicans were cool on impeachment, with some lawmakers admitting they didn’t have such a strong basis for impeachment and were, essentially, openly in search of one.

To this point, the House GOP’s investigations into the Biden family—particularly Hunter Biden’s activities while his father served as vice president—have been handled by the House Oversight Committee, led by Rep. James Comer (R-KY).

Much of the material they have framed as most damning, like Hunter Biden’s business dealings in Ukraine, was, ironically, scrutinized and litigated in Trump’s first impeachment. Many of the GOP’s core impeachment claims now, like the allegation that Biden ordered the firing of a prosecutor looking into a Ukrainian company—Burisma, which his son was working for—were debunked then.

Still, the Oversight Committee’s activities fueled many Fox News and Newsmax appearances, as Republican lawmakers talked up their findings. With GOP base voters clearly expecting serious action from the House, the tone of senior lawmakers grew more serious after a closed-door Oversight interview with Devon Archer, Hunter Biden’s former business partner, who indicated that the then-vice president was more aware of his son’s business activities than he insisted.

Even as those investigations ramped up, GOP lawmakers have continued to admit they have not found evidence to suggest that Biden himself might be guilty of impeachable offenses.

Over the weekend, Rep. French Hill (R-AR) said on CBS that he doesn’t believe Republicans have “even remotely completed their work on the kind of detailed investigations and quality work that Speaker McCarthy is expecting both those committees to produce before someone goes to, you know, an impeachment activity.”

Rep. Dave Joyce (R-OH), meanwhile, said recently he is “not seeing facts or evidence at this point” that would justify an impeachment inquiry.

Amid the palpable unease over impeachment, several Republican lawmakers insisted that McCarthy has not made an official vote—or widespread GOP support—a fait accompli.

“I wouldn’t be pre-committed to a course of action,” said Rep. Dan Bishop (R-NC), an archconservative lawmaker who held out on supporting McCarthy’s speakership.

Rep. Kevin Hern (R-OK), chairman of the conservative Republican Study Committee, had a similar answer. “If there’s no there there, then there’s no there there,” he told The Daily Beast. “Then we say ‘Hey, you were right, we were wrong, let’s move on down the road.’”

Both lawmakers downplayed the notion that the party base was pushing McCarthy, or the party writ large, toward a predetermined outcome.

“Most of my base voters that I encounter want me to do something up here, but nobody’s ever told me you just do it, regardless what the facts are. I haven’t heard it that way,” Bishop said. “They’d like to have an explanation why nobody’s doing anything, apparently, about a number of things, from their perspective.”

Like many Republicans, Hern seemed confident that an empowered impeachment inquiry would unearth the kinds of revelations that would form a persuasive case against Biden in a Senate trial.

“You have to make it so damning that Democrat senators would go to Biden and say, ‘I can’t support this,’ just like Howard Baker did to President Nixon back in the day,” Hern added.

Hern is not the only Republican imagining a Senate impeachment trial, given the facts at hand.

Asked if he’d thought about what a trial might look like, Buck scoffed.

“It’d be a joke!” he said. “What evidence do you present that there is a connection between Hunter Biden’s activities and Joe Biden at this point? It’s a joke.”