In the 1970s, an Englishman named Ted Lewis published three rowdy yarns about a brutal Briton working as an enforcer for a gangland “firm.” The first of these inspired a suitably gritty crime film recalled as one of the era’s best. The next two books weren’t so successful. But now, 32 years after Lewis’ death, his Jack Carter novels are getting a second life here in the States.

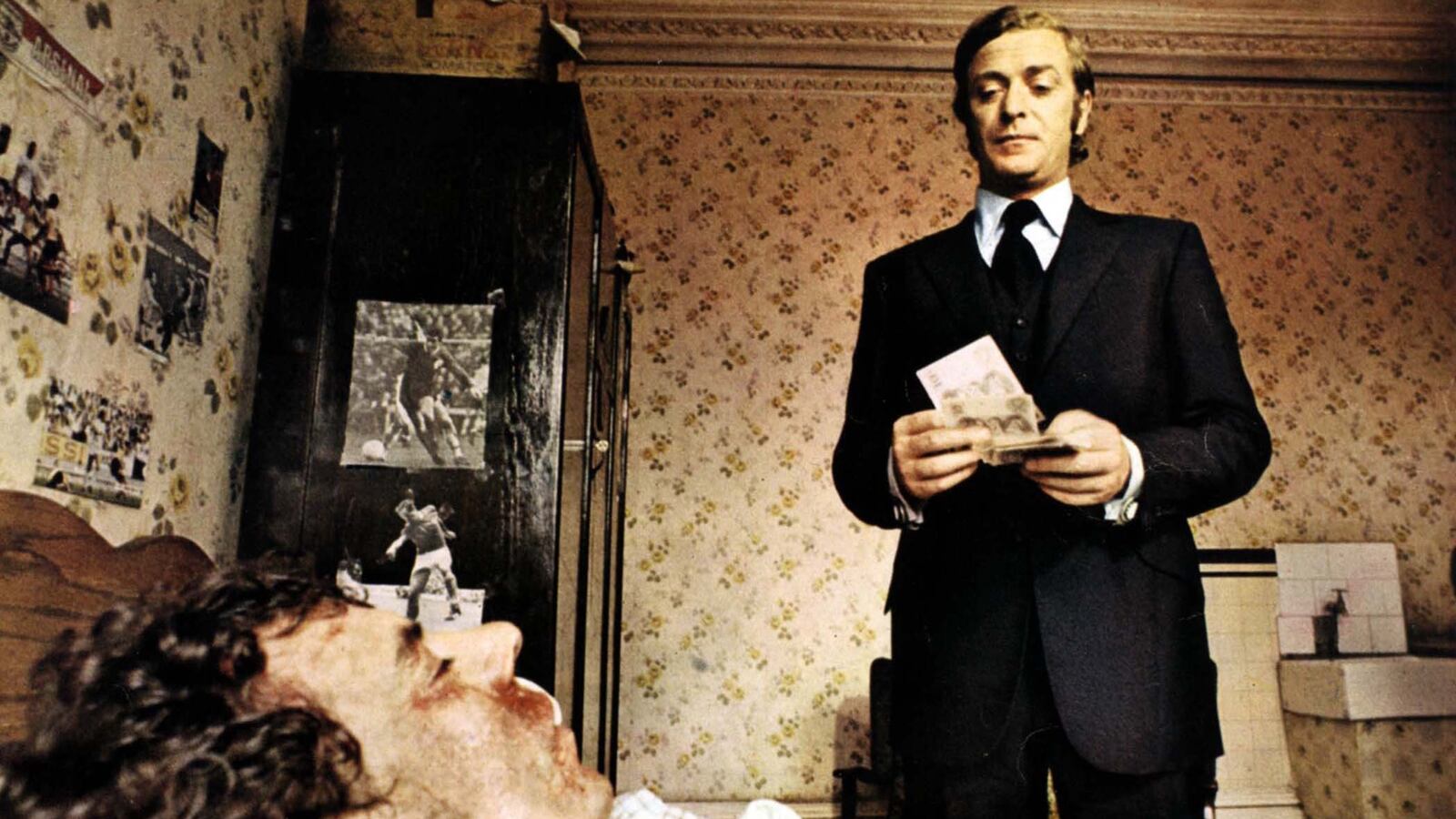

Fans of Get Carter, Mike Hodges’ 1971 movie, surely remember the exploits of the unflappable brute. As played by a young and rugged Michael Caine, Carter was a bitters-drinking, blade-wielding get-even artist who managed to make the act of eating soup on a moving train look menacing. Yet readers coming to the novels fresh won’t quite know what Lewis’ leading man is all about. So before we get to the enterprising small publisher responsible for reviving the books, and the brief but artistically fertile life of the man who penned them, let’s (re)acquaint ourselves with Carter’s CV.

It’s probably best to start with an explanation of how he became the top organized-crime fixer in the city he calls “the smoke” (i.e. London). As he puts in Jack Carter and the Mafia Pigeon, the series’ third novel, “it hasn’t exactly been unknown for me, as a matter of policy as far as the firm’s concerned, to see to transgressors from members of the opposition on a more or less permanent basis, the more or less depending on the degree to which your religious beliefs extends.” A history of violence and a gift for understatement—that’s Carter, a remorseless pulp fiction killer. In your standard crime tale, he’d be a one-dimensional foil for an emotionally-tortured-but-inherently-good cop. Here, he’s the one setting the agenda, and the police—“scuffers,” as he dismissively calls them—are nothing more than corrupt and ineffectual bystanders.

All three Carter novels are being reissued this fall, in handsome paperback editions, by a new imprint called Syndicate Books. The first, Get Carter—originally published in 1970 as Jack’s Return Home—follows our man as he treks from the capital back to his native Northern England, where his brother Frank has been found dead in suspicious circumstances. As he tries to figure out how Frank met his end, Carter quickly becomes a multidimensional character. His personal life is predictably messy—he’s planning to run away with his girlfriend, who happens to be his boss’ wife—but he has an idiosyncratic moral code and an almost touching appreciation for family values. When Carter realizes that his orphaned niece could use a father figure, he gamely tries to fill the vacancy. Alas, there’s not much evidence that he’s equipped to look after anybody but himself.

Lewis’ follow-up, Jack Carter’s Law—it appeared in 1974—is a spirited prequel that tracks Carter’s progress as he hunts down a purported “grass” (a snitch). Set against a backdrop of smoky billiard halls and gentlemen’s clubs in which chivalry is, in fact, dead, it’s a merciless novel in which pistols are brandished, head-butts are administered and lives are summarily taken. Five rapid-fire murders are committed in a single scene. A representative bit of Carter’s narration: “I smash him so hard that his head bounces off the window and he finishes up with his face on my shoulder.”

In Jack Carter and the Mafia Pigeon, released in 1977, Carter is sent to Majorca to babysit—and eventually liquidate—an American mobster. If its predecessors are tense and caustic, the third novel is a relatively jokey affair. Much of the humor is derived from Carter’s discomfort at being away from England. To him, the “thick uniform blueness” of the Mediterranean sky calls to mind “a sketchy backcloth on BBC2.” There are several untimely deaths, but the violence can feel forced, and the book’s many quips leave the impression that Lewis was more interested in crafting a gangster’s comedy of manners. The book’s two female characters, meanwhile, are cartoonishly portrayed, and they do little more than speak in double entendres meant to convey just how desperate they are to get Carter in the sack. Though it’s the most recent of the three books, it’s the one that hasn’t aged all that well.

On the whole, though, the novels are a welcome surprise to those of us whose only knowledge of Carter came via the big screen. The reissues are the first from Syndicate Books, an imprint that says it plans to put out up to 10 titles a year, mainly “out-of-print or neglected mystery and crime fiction of merit.” Syndicate was founded by Paul Oliver, the director of marketing and publicity for Soho Crime. In partnership with Penguin Random House, Soho will promote and sell the Carter books and future Syndicate titles. Until they were revived by Syndicate, the first two novels in the series were out of print in the U.S. for 40 years, and the third had never been published here at all.

Oliver says that Syndicate has its roots in the many forgotten titles that cycled through the Phoenixville, Penn. bookstore he used to own. “Some of them were out of print for a good reason (they were dated) and others were simply not very good,” he said in an e-mail. “But occasionally you stumble on a book that is remarkable, perhaps even has an important legacy (like Get Carter) and yet is lost to readers. That’s what I want Syndicate to be all about. Those kind of books.” He said Syndicate’s 2015 slate includes another Lewis novel and previously out-of-print “domestic thrillers with a sneer and an edge” by the late Margaret Millar.

Each of Syndicate’s reissued Jack Carter tales comes with an essay designed to help place the novels and their author in context. The most useful of these is by Nick Triplow, a British writer working on a biography of Lewis, who published other books aside from his Carter novels. In an afterword to Jack Carter and the Mafia Pigeon, he notes that although many successful crime writers cite him as an inspiration—the most prominent of these is probably David Peace, the author of the great, grim quartet of Red Riding novels—Lewis remains more or less obscure. “Partly,” Triplow writes, this is “because his early death at the age of 42 in 1982 denied him the second act and critical re-reading his work demanded. He left little other than his published work and the memories of those who knew him. No formal archive or collections of correspondence exists, only a few pieces written about him for magazines, most in the 1990s, when a laddish cultural resurgence rediscovered Carter and, to a lesser extent, Lewis, as some kind of Brit-bloke icon.”

Lewis drank a lot, for a long time, and Triplow says he was done in by “an alcohol-related illness.” Though the more sensational aspects of his Carter novels aren’t drawn from his own experiences, things seem to take an autobiographical turn when he discusses the ruinous effect of heavy boozing. In Jack Carter’s Law, he describes a bar full of morning drinkers: “except for the runniness round the rims of their eyes you’d never guess that they’d had to pour themselves a sherry before they could get out of bed and most of them will have spent an hour shaking on the toilet (or over it) before restoring some kind of humanity to their bodies.”

Lewis seems to have possessed a one-man-against-the-universe sensibility. This comes through most effectively in Get Carter. Surveying the gauche affectations of the newly wealthy in his working-class hometown, Carter gets a rush of pride—he might be a criminal, but at least he’s not like them: “Not one of them was not overdressed. Not one of them looked as though they were not sick to their stomachs with jealousy of someone or something. They’d had nothing when they were younger, since the war they’d gradually got the lot, and the change had been so surprising they could never stop wanting, never be satisfied. They were the kind of people who made me know I was right.”

A fictional thug made these observations in a novel that’s now almost 45 years old. Revisited today, amidst talk of economic inequality and class warfare, Carter’s righteous anger feels plenty relevant. Though Lewis wrote crime fiction, not political tracts, his work clearly wasn’t untouched by the real world.