Andrew Cuomo had just finished addressing New Yorkers, saying that the sexual harassment allegations were unfair and politically motivated, a product of changing social mores and misinterpreted efforts at connection with underlings, when, towards the speech’s end, he abruptly pivoted. None of that mattered. He was quitting, he said, instead of being a costly distraction for New Yorkers.

“For the good of the country, right?” said Rich Little, sitting with pleated khakis and his loafers perched on a plush couch in the empty lounge room of his midtown Manhattan hotel, in a tone that suggested he knew the lines of political rhetorical bullshit before they were even uttered.

If you don’t know who Little is, ask your parents, or, more probably, your grandparents. Little was something of a star in the 1960s and ’70s, when amidst cultural tumult, he was a reassuring presence at Vegas nightclubs like the Tropicana and on late night talk shows, mostly as an impressionist of presidents, in particular Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan.

It was edge-less enough that Little was a frequent White House guest; after Stephen Colbert lampooned much of the inside-the-Beltway political culture as the keynote of the 2006 White House Correspondents Dinner, Little was brought in the next year as a palette cleanser.

And Little is here, in New York City, sitting in this room of heavy furniture and faded opulence because he is making his New York theatrical debut at age 82 in a new play, Trial on the Potomac: The Impeachment of Richard Nixon. The play begins with Little, trying to tone down the campier bits of his Nixon impersonation, addressing the nation, and instead of saying that he is stepping down because “I must put the interest of America first,” he says he is not stepping down in order to put the interests of America first, and will instead put a defense in his impeachment trial.

This Nixon, in other words, does the reverse Cuomo, and goes on to defend a reputation sullied by history. It is the only way forward, the play suggests.

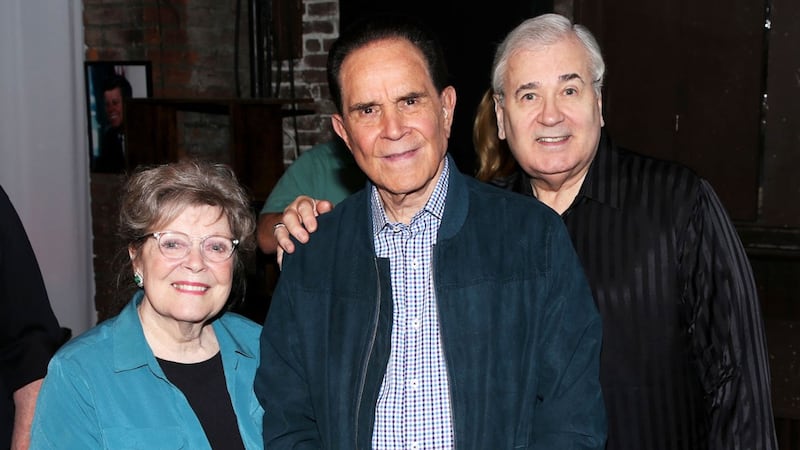

“I tell you, he hasn’t got much of a future,” Little said of Cuomo while George Bugatti, another Vegas mainstay as a singer/songwriter and pianist and the writer of the play sat beside him.

“Everywhere he goes people will say, ‘Look, that’s Andrew Cuomo. Stay away from him. He’s bad news.’ So he is going to have a tough time existing. If he goes to a restaurant he will be joked about, people will move away from him. If I were him I would move to another country, take all the money he made from his book, move to an island somewhere…”

“And molest a pygmy!” shouted Bugatti.

Bugatti insisted that his play, which borrows heavily from the book The Real Watergate Scandal, a revisionist history by Geoff Shepherd, a Nixon administration lawyer, is just a play, nothing more. But the play suggests, and Bugatti told me he believes, that Nixon’s culpability, either in directing the Watergate break-in or during the cover-up, was zero, that Nixon was ill-served by the people around him who were looking to preserve their own reputations, and that the president resigned just for the good of the party.

In Bugatti’s play, the president is done in by John Dean, his top aide who is trying to save his own reputation. Yes, he said some incriminating things on tapes, but those tapes were just a couple of guys and the president shooting the bull, not actually planning to satiate their paranoia and plan an elaborate operation against their political opponents.

Nixon, says Little, “lied, he covered up some things, but I think Watergate is bunch of guys breaking into Daniel Ellsberg’s office and, and trying to steal stuff and screwing the whole thing up. They didn't even lock the door. I mean they were a bunch of idiots. They were the Marx brothers, you know, and it just wasn’t that big a deal.”

“Ellsberg stole the Pentagon Papers, and they didn’t know what else he had stolen,” Bugatti added. “It could be strongly argued that they needed an operation to get into Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office for national security reasons. So they broke in, but they bungled it. They were like a bunch of keystone kops. But that’s why the White House did it.”

Little then jumped in with a riff about Nixon’s face, how the kids used to wear Nixon masks at Halloween and how if Nixon had been added to Mount Rushmore his nose could have doubled as a ski jump.

“If Watergate happened today it would be a little item in the back of the newspaper,” he then said. And it would probably just go away in a few days. Some guys broke into one office and tried to steal some stuff and they got caught and it's nothing to do with Nixon and, you know, no big deal.”

It is not hard to imagine that Trial on the Potomac would be the kind of thing that would have appealed to the Q-Anon adherents of the early 1970s if such a thing had existed.

It portrays a shadowy world of Washington insiders where nothing is quite as it seems. The whole Watergate mess is spurred on by Ted Kennedy, who, in between generous swigs of the whiskey bottle he keeps in his desk, is strategizing how to run for president in 1976. He has all of official Washington in his prodigious pockets, and even Nixon acolytes scurry for his favor lest they be seen as too tied to Nixon, that yokel from Yorba Linda, the president of the United States.

As the Nixon trial proceeds in the Senate, Kennedy barks to an aide that the Nixon lawyers have “dug up a lot of shit, but we still control the press. Get me Ben Bradlee at the Washington Post. And then Tony Lewis at the New York Times, and then Mary McGrory at Newsweek. Let's get them to spin this our way before it gets too big to contain,” which is exactly the kind of thing a senator says who is not actually a senator but has seen one played on TV.

If the play tries to portray the Watergate burglars as a bunch of bumblers, the all-powerful conspiracy aligned against Nixon at least lacks discretion, even without their every word being recorded.

“Look, I ran those trials for you, I gave you Nixon’s men on a plate. I did my part,” says Judge Sirica, the district judge who ordered Nixon to turn over his Oval Office recordings, to some of Kennedy’s aides, only later to confess to one of Nixon’s lawyers that the president had to be impeached in order to limit Republican losses in the next election.

“The Deep State knocked, we answered!” Sirica says.

This reference to “the Deep State”—a phrase that has only come to prominence recently, mostly by Donald Trump and his supporters to explain how the federal bureaucracy was out to get him—isn’t the only relevant contemporary echo in the play. There are references to “the phony news” as well, and towards the play’s end, when Nixon has ‘em licked, he stands in the well of the Senate and says that he knows that the Kennedy forces stole Illinois from him in the 1960 election, but even as JFK and their swell allies in Georgetown cocktail parties mocked his hardscrabble upbringing, he did the right thing and conceded defeat.

There is even the implication that the Democratic National Committee is running a prostitution ring out of their offices, which is almost precisely the conspiracy theory that led a crazy gunmen to nearly shoot-up a Washington, D.C., pizza joint in 2016.

“Just like Trump,” said Little. “He won the election. He didn’t get that many votes and not become the president. It’s amazing how much the Democrats hated Donald Trump, and they still do. Everyday you read they want to put him away in prison. They’re still after him because they think he's coming back and they're terrified.”

Trump did not win the 2020 election. What is Little’s evidence that Trump won?

“When you saw on television, especially on Fox, when you see Trump out on the trail before the election and there are 25, 30,000 people going crazy. And then there's Joe Biden talking to six cars. So, you say to yourself, this guy has no chance in hell of winning. Look what Trump's doing, holy shit, look at all these crowds, look at all these people going crazy. Joe Biden's got nobody and he's hiding in his basement.”

Little got up and started doing his Biden impersonation, which mostly consisted of an old man shuffling along and staring at his feet, shouting at the press to ask him questions and then not remembering where he was.

“What about your son Hunter Biden? What about all the crime in the U.S.? What about the problems on the border?” he said, then in a slightly modulated Biden voice Little waved and said, “Hey man! Thanks for coming!”

He sat back down. “I am going to try to do that when I get back to the Trop,” he said.

Little took out his phone and stared at it. “I got a text here I don’t even know who it is from. It says ‘Better start doing your Cuomo. Trial on the Catskills.’” Little and Bugatti both let out an uproarious laugh. Little said he didn’t have a Cuomo impression, but he did have a Como impression, as in Perry Como, and he started singing “Call Me Irresponsible.”

“Call me irresponsible, call me unreliable, and groping womeennnn tooooooooo.”

“Groping women too!” Bugatti said, slapping the couch where he sat. “That’s cute.”

Little got up, said he had to be somewhere, and made plans with Bugatti to meet for supper, and walked out of the room. Alone, Bugatti tried to explain what he was doing with the play.

“I’m of the belief that multiple narratives can exist at the same time, and it doesn’t mean that they all have to be right. It’s the whole point of view thing. I’m sitting here and I see that you're wearing a striped blue shirt, but a guy who’s sitting in the back will say I think the shirt was dark because all he really sees is your dark jacket. It’s wrong but it’s his point of view, so it was interesting for me as a playwright to show an alternative point of view. And that’s what I did.”

“I’m not political,” he added. “I’m not smart enough for that. I read the research though and I’m a writer. I’m an artist. A bullshit artist, I guess.

“No!” he added. “Don’t write that down!”