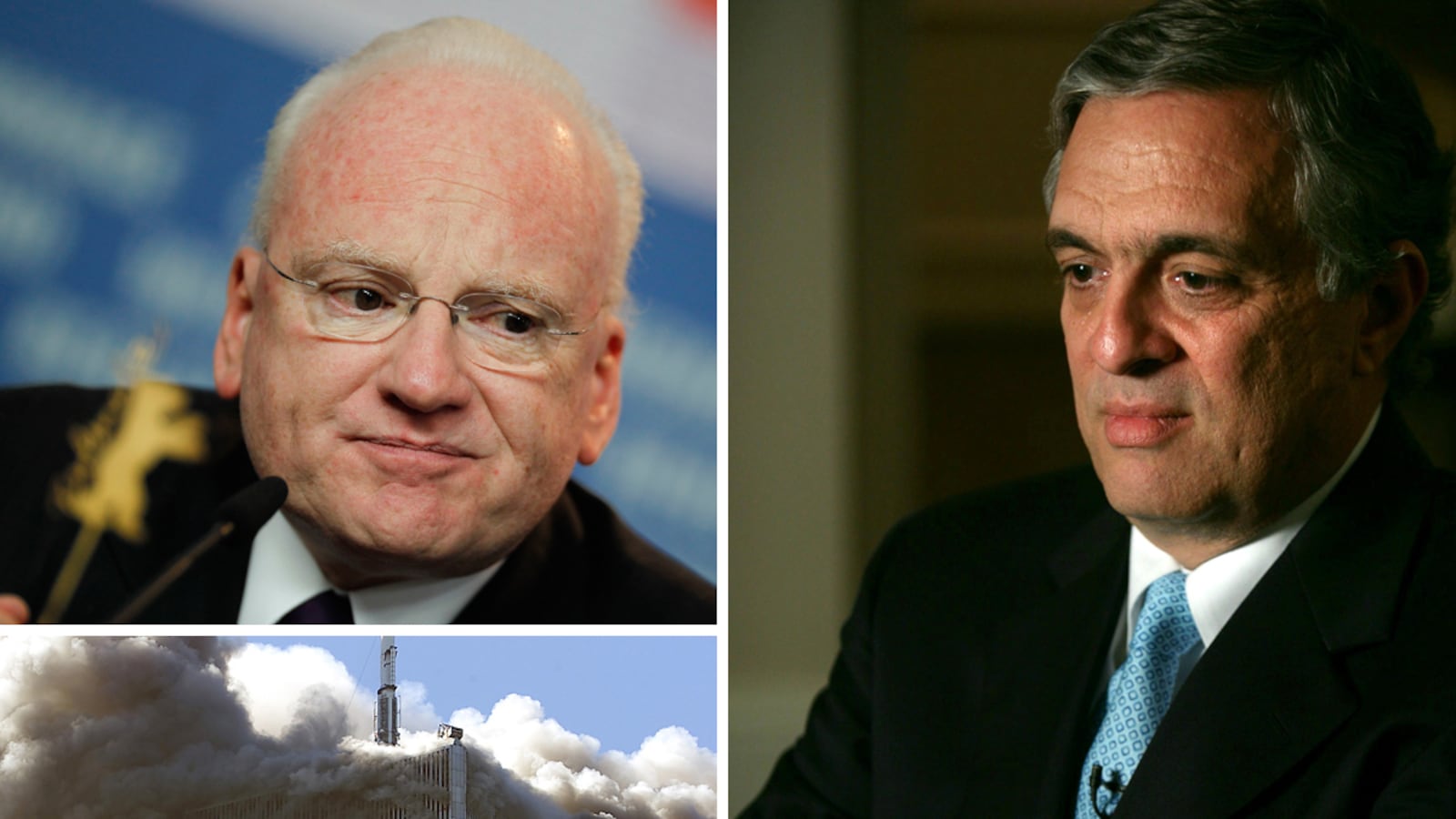

Former White House counterterrorism coordinator Richard Clarke has reignited controversy by speculating, in an interview cited in Thursday’s Daily Beast, that the CIA intentionally withheld advance knowledge of two of the 9/11 hijackers from the White House and the FBI, in an attempt to cover up the agency’s failed effort to recruit the two men as assets.

Clarke’s comments—and immediate, emphatic denials from former CIA director George Tenet and two senior CIA officials involved—go to the core of one of the enduring enigmas about 9/11.

Things began to unravel for the CIA on the day of the attacks, just four hours after the Qaeda strikes, according to research we conducted for our new book, The Eleventh Day. Soon after 1 p.m. that day, at agency headquarters in Langley, an aide handed Director Tenet the passenger manifests for the four downed airliners. “Two names,” he said, placing a page on the table where the director could see it, “these two we know.”

Tenet looked, then breathed, “There it is. Confirmation. Oh, Jesus ...”

There on the manifest for Flight 77, listed as traveling in first class, were the names of Nawaf al-Hazmi and his brother, Salem. Also on the manifest, near the front of the coach section, was passenger Khalid al-Mihdhar.

The names Hazmi and Mihdhar were instantly familiar, Tenet has said, because his people had learned only weeks earlier that both men might be in the United States. According to the director’s version of events, the CIA had known of Mihdhar since as early as 1999, identified him as a terrorist suspect by December that year, had him followed, learned he had a valid multiple-entry visa for the United States, and placed him and comrades—including Hazmi—under surveillance for a few days in Southeast Asia. Later, in the spring of 2000, the agency had learned that Hazmi, who also had a multiple-entry visa, had arrived in California.

The director said after 9/11, though, that—in spite of having gained such dynamite information—the CIA had done absolutely nothing about it. The agency had not asked the State Department to place the two terrorists on watch lists at border points, nor asked the FBI to track them down if they were in the United States—not until 19 days before 9/11. The omission, according to the CIA, was simply the result of multiple mistakes.

Historical puzzles are as often explained by screw-ups as by darker truths. What is known of the evidence on Hazmi and Mihdhar, however, makes the screw-up version hard to swallow. Not least because the CIA version of events suggests its officials blew chances to grab the two future hijackers time and time and time again.

At the heart of the suggestion that the agency intentionally withheld information was the discovery by the Justice Department’s inspector-general of a draft cable—one that was prepared but never sent—by an FBI agent on attachment to the CIA’s bin Laden unit.

In January 2000, having had sight of a CIA cable noting that Mihdhar possessed a U.S. visa, agent Doug Miller had swiftly drafted a memo on the matter addressed to the bureau’s own bin Laden unit and its New York field office. Had that memo been sent, the FBI would have learned right then of Mihdhar’s entry visa. The report was blocked, however, on the order of then-deputy chief of the CIA’s bin Laden unit, Tom Wilshire.

Why did he block it? Could it be that the CIA concealed what it knew about Mihdhar and Hazmi because officials feared that precipitate action by the FBI would blow a unique lead? Did the CIA want to monitor the pair’s activity itself, even though its mandate does not allow it to run operations in the United States? Or did it, as some bureau agents suspected—and Clarke has surmised—even hope to turn the two terrorists, to recruit them as informants?

Clarke’s speculation may not be idle. A heavily redacted congressional document shows that in early December 1999, before Mihdhar’s U.S. visa came to light, top CIA officials had debated the lamentable fact that the agency had as yet not penetrated Al Qaeda:

“Without penetrations of OBL organization ... [REDACTED LINES] ... we need to also recruit sources inside OBL’s organization. Realize that recruiting terrorist sources is difficult ... but we must make an attempt.”

The following day, CIA officers went to the White House for a meeting with a select group of top-level National Security Council members. Attendees discussed both the lack of inside information and how essential it was to achieve “penetrations.” Many “unilateral avenues” and “creative attempts” were subsequently to be tried. Material in the document on those attempts remains redacted in its entirety.

Though fragmentary, there are pointers suggesting that the CIA may not—as it claimed—have promptly dropped its coverage of Mihdhar. On Jan. 5, 2000—the day on which Miller wrote his draft cable, a CIA bin Laden–unit officer noted of Mihdhar and Hazmi that “we need to continue the effort to identify these travelers and their activities.” As late as February, moreover, a CIA message noted that the agency was still engaged in an investigation “to determine what the subject [Mihdhar] is up to.”

In 2007, Congress forced the release of a 19-page summary of the CIA inspector general’s long-secret probe of its pre-9/11 performance. The summary acknowledged that agency staff had neither shared what they knew about Mihdhar and Hazmi nor seen to it that they were promptly placed on watch lists. An accountability board, the summary recommended, should review the work of named officers, including former director Tenet. Tenet’s successor, Porter Goss, however, insisted that there was no question of misconduct by the named officers. They were, he said, “amongst the finest” the agency had.

Richard Clarke’s comments reopen the debate about this troubling episode. The CIA’s “screw-up” explanation of its lamentable failure to act, having learned that two known bin Laden terrorists were headed for the United States, remains at best unconvincing, at worst indicative that it conceals a very different, secret scenario.

Anthony Summers & Robbyn Swan are the authors of The Eleventh Day: The Full Story of 9/11 & Osama bin Laden, published this month by Ballantine.