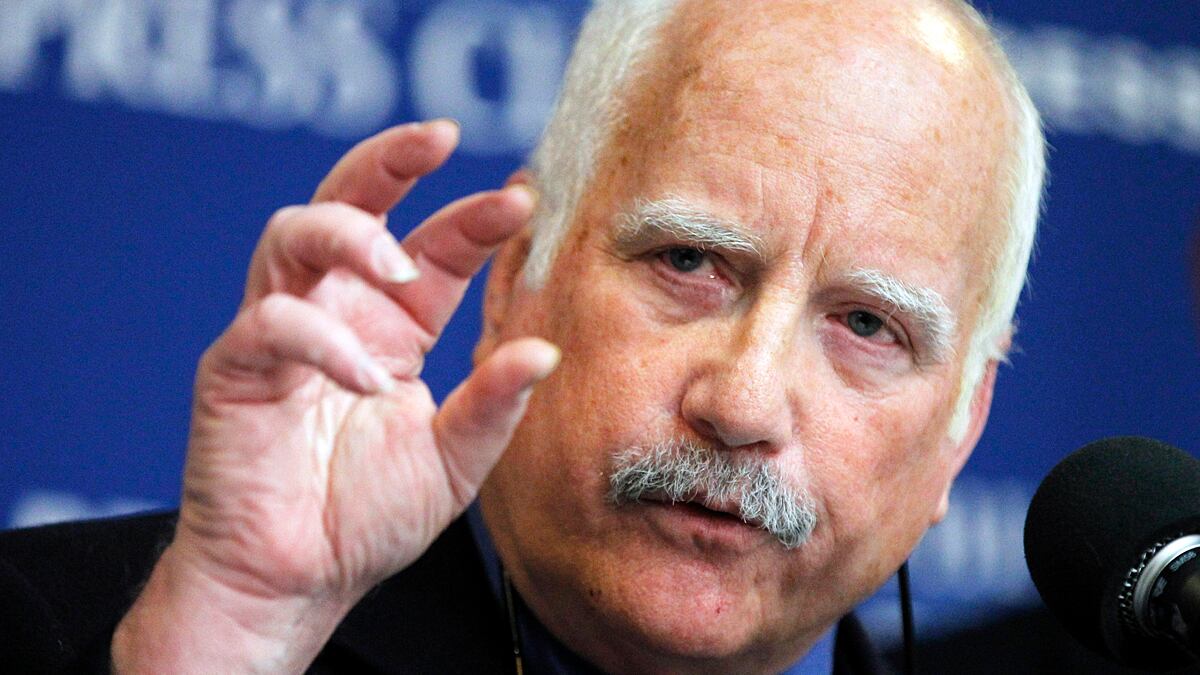

The actor Richard Dreyfuss was in Washington on his way to Philadelphia, where he was to unveil several initiatives to promote civic education in America, including a history-play competition with $350,000 in prize money and “learning modules” to promote the core values of critical thought and reasoned debate that the founding fathers exemplified. Eager to talk about his lifelong love of history, he lamented the state of today’s politics and how excessive partisanship has crowded the political space needed to address the country’s problems.

He was on a roll only to suddenly volunteer, “When you Google me, you’ll find a lot of people don’t like Richard Dreyfuss.” And why is that? “Because I’m cocky and I present a cocky attitude,” he declared without apology. “But no one has ever disagreed with the notion I represent, that we need more civic education. So far there’s 100 percent support for that.”

Dreyfuss is an accomplished actor with a long film career of standout roles in movies as varied as 'Jaws' and 'What About Bob?' He won an Oscar in 1978 for 'Goodbye Girl.' He is also known as an outspoken liberal activist, and for a time was promoting the impeachment of President George W. Bush. “Most of the people I knew targeted Bush as the enemy, the villain,” he said. Dreyfuss moved on, concluding that the absence of outrage against the Bush administration’s use of torture and civil liberties abuses meant that “the enemy was us, and we had to figure out solutions.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Those solutions, he believes, include a deeper knowledge of the nation’s history, and the forces that gave rise to the Bill of Rights and the documents that form the foundation of our democratic republic. He doesn’t mind that Sarah Palin and Michele Bachmann are getting some of the details wrong; he just wants more attention paid to the extraordinary efforts of those who shaped the country. He has two film projects in mind, one about the Philadelphia Convention and how George Washington’s stoic presence kept it from unraveling; the other about the battle of Appomattox, after which the Confederate Army surrendered, and the nation was reborn.

“It can’t be partisan,” Dreyfuss says of his civics initiative, though there are continuing battles over multiculturalism and the merits of presenting the founding fathers warts and all. He favors what he calls “glory tales and myths” for the early grades, with the more complex aspects of a life introduced later. He’s in negotiations with Shepherd University to establish a George Washington Institute on the Enlightenment, a place of scholarship for the period leading up to American independence, and he’s restoring the West Virginia home, “Happy Retreat,” of Charles Washington, George’s brother, to serve as the headquarters for The Dreyfuss Initiative.

Dreyfuss doesn’t just speak; he tends to rant. And he spent several years doing that, giving such impassioned talks around the country to teachers, school superintendents, Rotary Clubs, Girl Scouts, whoever would listen. By his count, he spoke to some 170,000 people over five years. “I had no plan except to speak to as many people as I could.” The turning point came when he spoke to 600 Republican women in Palm Springs. When a lone man stood up and said he’d heard enough, the women booed the man. Several women then confessed that they’d attended Dreyfuss’ lecture intending to walk out on him, but discovered they agreed with everything he said.

Dreyfuss comes from an activist family, and speaking out is what he does. The only difference now, he says, is that he’s focused on one issue. “I’ve drawn the line,” he says. “I will not give up the America that I was taught about in the fifth grade, and that Frank Capra ('Mr. Smith Goes to Washington') showed me—and that my father fought for in the Battle of the Bulge.” People across the ideological spectrum can agree with those ideals, which is why Dreyfuss has found so much agreement in his campaign for more civic education.

Not everyone might share his motivation in the sense that he wants to avoid another crackdown on civil liberties in the event of another terrorist attack on U.S. soil. He imagines that a future attack could be non-ideological. After all, terrorism is a tactic not an ideology, and a disgruntled group could carry it out for whatever reason. He imagines it occurring in Disneyland, with hundreds of children the victims, “and the next day we’ll have passports to go from Denver to Los Angeles.” It may be fanciful to imagine that kind of hysterical overreaction can be prevented by a better grounding in history, but a greater knowledge of who we are as a people, and what shaped us, surely can’t hurt.