Richard Ford’s masterful new novel, Canada, opens with a bang: “First I’ll tell you about the robbery our parents committed. Then about the murders, which happened later.”

Those lines were the first thing he wrote, after 20 years of thinking about the book, he said. “People have said it seems nervy of me of give away so much. But that’s not how I thought. I thought if I gave away those big events, then I’d have to find other, more important and interesting events to tell.”

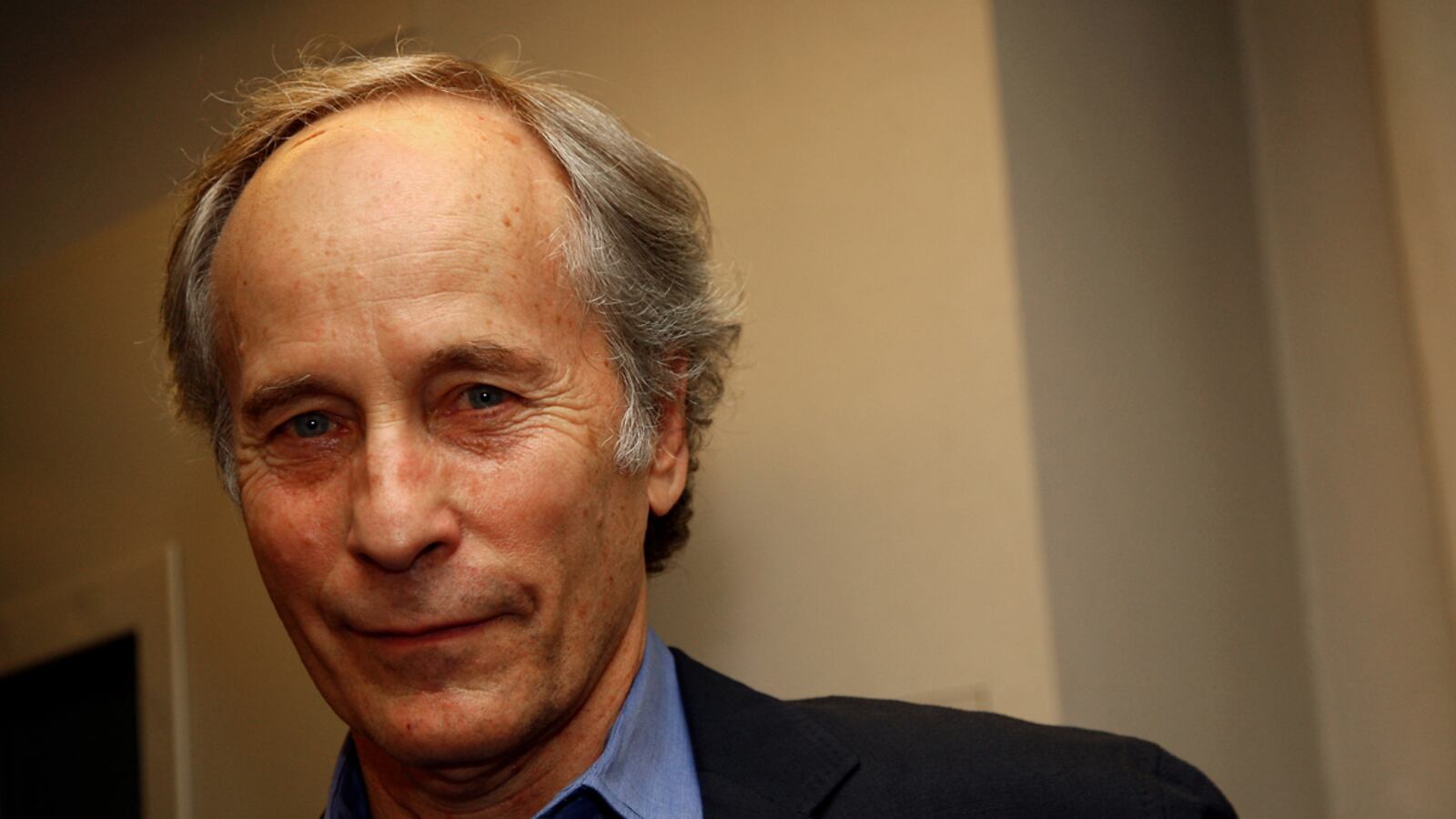

Ford was answering my questions from his writing space in a converted boathouse in East Boothbay Harbor, Maine, where he sits facing the ocean and the osprey nest on Perch Island. I’d visited him and his wife, Kristina, there in 2003, the year we collaborated, along with Amy Tan, Michael Chabon, and others, in sponsoring Oakley Hall, a Ford mentor at UC Irvine’s M.F.A. program, for the Poets & Writers’ lifetime-achievement award.

Are the osprey nesting? I asked. “The ospreys are here at this very moment,” he answered. “That said. I turn my table away from the window. My job is to come up with vivider pictures than I can see.”

No one thing inspired Canada, Ford said. “From the start, I wanted to write a novel about a teenager who’s abandoned and sent away to Canada. Something about crossing borders—of various kinds—seemed dramatic; how close one state of being is to a very different state of being.”

Canada is set in part in Great Falls, Mont.—the location of several earlier short stories (in Rock Springs, his vaunted 1987 collection) and his short novel Wildlife (1990).

“At first, I just liked the name Great Falls. Liked seeing it in sentences. I started setting stories there well before I ever went there. It seemed untouched in a literary way (although it wasn’t ... I just didn’t know about what had been written about it). Great Falls, itself, has a dramatic landscape—the front range to the west, the plains to the east, the Missouri River makes its epic turn east there, it’s relatively close to Canada (which interested me); there’s an Air Force base there, and all the life that accompanies that. It just seemed to be a town where I could make anything happen that I wanted happen. Plus I really liked it. Still do like it. I’m—I guess—by nature a writer who returns to subjects. It must be I think that each time write about something (Montana, New Jersey, real estate, families in distress) I open opportunities for later, even fuller consideration.”

Ford’s narrator, Dell, is 15 when his life changes. Is there anything in Ford’s own boyhood that ties into this work? “If I say there is, then my completely imaginary novel automatically becomes ‘autobiographical.’ But. I did grow in a town—Jackson, Miss. (a long way from Great Falls)—where my mother and father were unaffiliated. They were from Arkansas, and only settled in Jackson so I could be born there. I grew up feeling not connected with the larger forces of a culture I was by accident born into. Family was all that held us together. I don’t think that makes Canada autobiographical, though. All novels ultimately reveal what the writer considers to be important.”

Once Dell has crossed into Canada to live, avoiding a Montana orphanage in a plan his mother has set up, he works for his guardian’s hotel, and also helps with the goose-hunting season. Hunting is a perennial subject for Ford, whose father and grandfather took him hunting as a boy, mostly in Arkansas. “I still go hunting 58 years later—with Kristina, now. Dave Carpenter is a Canadian novelist and essayist who lives in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. A wonderful man, and a splendid writer. He took Ray Carver and me together on my first goose hunt along the South Saskatchewan River. That was in the middle '80s. That’s probably where Canada really got its start. It was my first time in the Prairie Provinces. It also made a very big and very positive impression on me.”

In the years since his triple crown wins (the Pulitzer and the PEN/Faulkner for his novel Independence Day, all in 1995), Ford has become something of a literary statesman. I saw him give a self-deprecatory and moving keynote speech about his boyhood neighbor Eudora Welty and overcoming dyslexia at the 2002 AWP (Associated Writers and Writing Programs) conference in New Orleans, and serve as a courtly interviewer at the 2010 PEN World Voices Conference, engaging novelist Shirley Hazzard in a conversation about “time, love, the coming around of inexorable events … the acceleration and dislocation of modern life.” (Video of that dialogue here.)

Ford’s new novel is rooted in the complex realm of the past, echoing with the reverberations of actions that change the course of several lifetimes irrevocably. What’s the advantage of telling the story from the point of view of a 15-year-old boy 50 years later?

“Well, since I once was a 15-year-old boy, it wasn’t very hard to write about one. It came naturally, and (so far) I have a very good memory. What telling a story in such a retrospect accomplishes—from the point of view of a 65-year-old man narrating his tempestuous youth—is that the nature of the story as told demonstrates that all that wild life can now be understood and accommodated. Narrating it that way is basically a gesture of optimism. At least that’s how I imagine it.”

Ford has spoken frequently of the importance of a moral vision in his work. “By ‘moral vision,’ I’m perhaps talking about something less grand and austere: namely, that the novel is putting on (I hope) vivid and irresistible display the consequences of our important acts ... If you lose your bearings, betray your family, act stupidly, rob a bank, go to jail ... well, then, there are some pretty precise things (not good things) that come along after, and people’s lives are affected.”

And what’s next? Ford says he has half a new book of a short stories written. “I’ll try to write a few more.”

Finally, a word about Kristina, who has been in Ford’s life since their undergraduate days at the University of Michigan. “Kristina’s pretty much in the middle of everything that I write. I don’t write about her, but her sensibility inspires a lot of what I write. And I do ask her to read what I write along the way; ask her to render opinions. Then when I’m at the end of writing a book first-time-through, she consents—in a busy life—to let me read the whole book to her out loud. Needless to say, it’s a very, very generous offering. It’s indispensable for getting all the words in their right places—which is kinda what writing novels is all about.”