Richard Hell was the first person to ever shoot up heroin in front of me.

We were “filming” the photo comic The Legend of Nick Detroit in early 1976, which would become the worst-selling issue of PUNK magazine ever, and I was picking up Richard at his apartment on East 12th Street. Just as we were about to go out the door, to the day’s location, Richard said, “Hold on a second.” Then he sat down at his little desk table, pulled out his homemade set of works, and stuck it in his arm.

And I thought, jeez, does he hafta do that every time he leaves the house?

Of course, 20 years later Richard wouldn’t let me smoke a cigarette in that same apartment, with the same desk, the same furniture. In fact everything was the same—except for Richard, who was now playing tennis with movie stars in the morning and enjoying his life.

Thank god, because those early days of punk were filled with endless hours of trying to scrape up enough money to buy something to get high on, while dreaming up get-rich-quick schemes and cursing the powers that be for not recognizing our hazy brilliance.

At that time, I thought that since the CBGB scene was so loaded with future stars—Debbie Harry, Joey Ramone, Patti Smith, David Byrne, Johnny Thunders, and, of course, Richard Hell—why wait for Hollywood to discover all this wonderful talent? Why not just write a story, take photos of everyone acting in it, and publish it in our magazine?

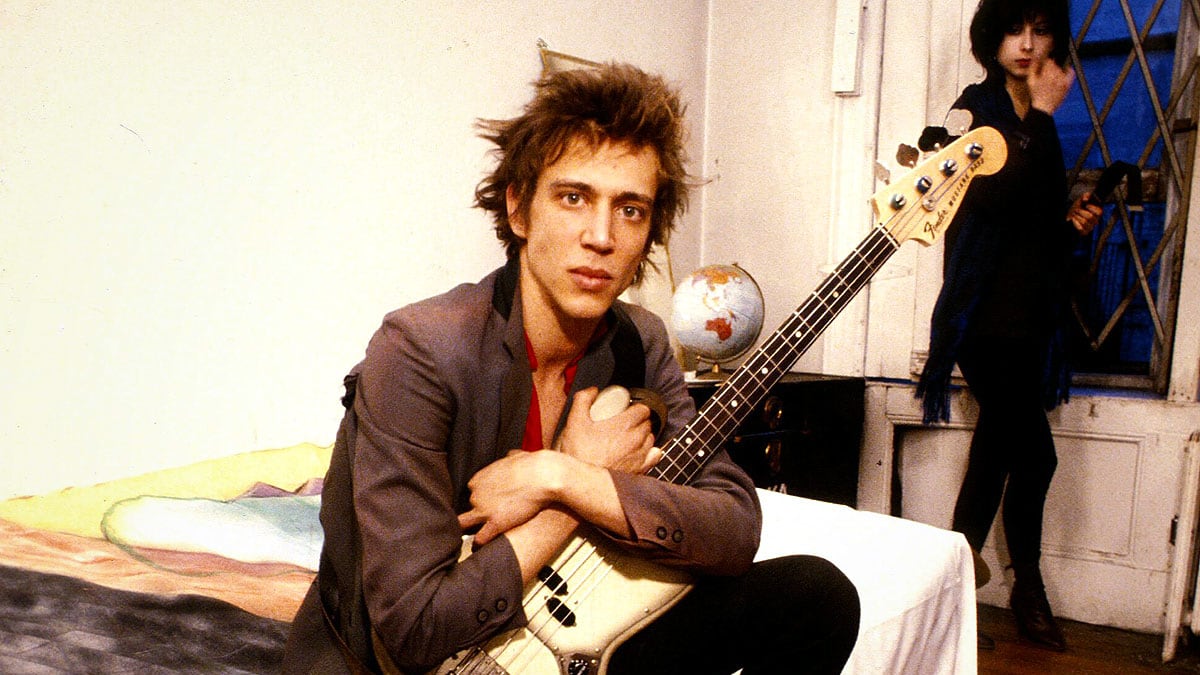

That’s when I got the idea to write a cute little story about a psychopathic ex–police detective, Nick Detroit, who gets called back to the force to learn why all the mobsters in town were being assassinated. The Legend of Nick Detroit was partially an excuse to get money to get high on. And it was partially an excuse to showcase Richard as the ultracool, removed, narcissistic ex–police detective. I knew that Hell was the punk version of Dirty Harry, so iconic looking with that hair, those cool shades—only with a gun in his hand instead of a guitar. (Which is why in every review of his new memoir, I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp, perhaps the worst book title ever, all the press still accompany the text with a photo from Nick Detroit.)

But Richard was thoroughly disgusted with me when we finished shooting Nick Detroit. He was pissed at the long hours and moronic script, as well as being dope sick, and on the last day of shooting, he took his revenge by lecturing me in some dive bar about how, after I died, he was going to erect some monument to unworthiness. Richard snarled, “I’m going to assemble some half-assed structure over your grave site that spells out the word ‘I-N-C-O-M-P-E-T-E-N-T,’ made out of some cheap building material, like plaster of Paris, so that it dissolves in the rain, like oozing shit that dribbles on to your grave.”

Yeah, Richard could be a prick alright, a regular Nick Detroit. And while I’ve been insulted over the years, the slurs were never as eloquent as Richard’s “oozing shit” speech. Even when he was an asshole, Richard never lost his gift to articulate the profane.

Which brings us to I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp, an excellent book for anyone who wants to know about the early days of punk. Richard was a fun-loving kid who grew up on television, ran away from home, got punished, moved to Manhattan, and started band with his best friend from Kentucky: Tom Miller, a.k.a. Tom Verlaine. With the creation of Television, Hell felt the dizzying power of molding the future, then quarreled with Tom, became a junkie, and left the band to start the Voidoids. And then he toured a bunch.

And while my recap is a bit simple, I Dreamed I Was A Very Clean Tramp is probably one of the most literate memoirs from anyone in a rock-and-roll band, and that’s because it becomes clear in the book that Richard values writers more than he does musicians. It’s also clear that Richard only detoured into rock and roll as a way to indulge his fantasies, but in the process wrote the punk anthem “Blank Generation,” as well as the few lines he contributed to Dee Dee Ramone’s classic “Chinese Rocks.”

What excited me about the book is that it has one of the best paragraphs articulating the rush he felt creating rock and roll:

All through this book I've had to search for different ways to say “thrill,” “exhilaration,” “ecstatic,” to communicate particular experiences. Maybe the most extreme example of this class of moment is what I'm trying to describe here. What it felt like to first be creating electrically amplified songs. It was like being born. It was everything one wants from a so-called God. The joy of it; the instant inherent awareness that you could go anywhere you wanted with it and everywhere was fascinatingly new and ridiculously effective. It was like making emotion and thought physical, to be undergone apart from oneself.

Nice.

Since I know Richard’s story and lived through quiet a bit of it, it’s hard to write a review of his memoir since it brings back so many other memories they aren’t in the book. Still, if you want to know what it felt like to be at the center of a musical revolution, read I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp.

What's remarkable about Richard, to me, is that he still remains as cool, funny, and iconic-looking as he did when we shot the photo comic. Of course, Richard remains one of the best—and laziest—writers I've ever met. I remember when we finagled an assignment from Spin magazine in the ’80s to travel on a raft down the Mississippi River and write an article about Huck Finn’s 100th birthday. We were to split the writing in half: I’d write the first day, Richard the second, alternating back and forth, and it was decided I would lead the piece off. And I was really proud of my effort on the introduction, thinking I'd really done something.

And I was excited to show it to Richard, who just sighed and then disappeared for a week and came back with such an exquisite piece of writing that I can still remember my two favorite lines from. The first was, “I love leaving, and what does a river do but leave?”

The other’s more to the point. “Somebody’s got to stick up for the mud,” which I always wished I’d written. I loved the line so much, I wanted to put it on a T-shirt and sell it—but since Gillian McCain and I had already stolen the title of our oral history of punk from a T-shirt Richard had made, I thought that might be pushing it.

Richard and I have remained friends throughout the years, though we don't talk as much as we once did. Probably because in the mid-’90s, Richard and I were invited, along with Kathy Acker and Allen Ginsberg, to speak with William Burroughs at some highbrow literary event in Lawrence, Kansas. Immediately afterwards, Kathy Acker died of breast cancer, then Allen Ginsberg went, and then William Burroughs. Both Richard and I wondered who was going to be next.

So Richard would call and drawl, “So Legs ... uh ... how ya feeling?”

And then laugh hysterically.