Clint Eastwood’s Richard Jewell is a film about a very sweet, earnest adult Boy Scout who saves the lives of hundreds of people by identifying a potential bomb at a concert during the ’96 Olympics in Atlanta and making damn sure that the police take the threat seriously. As Jewell and police officers try to get hundreds of people to clear the area, the bomb goes off; two people die, 111 are injured, but many more walk away alive or unscathed than the bomber intended (in the film, Jewell points out that this is not only because of his action, but also because a group of unruly kids accidentally tip the bag holding the bomb over, so it explodes up and not out). After it’s leaked that Jewell is a prime suspect in an FBI investigation into the bombing, the Boy Scout gets bullied by the very law enforcement he reveres as well as by media outlets that make a field day out of questioning his heroism.

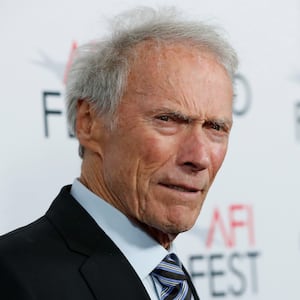

Much of the conversation around the film has gone away from Jewell, who was eventually cleared after repeated violations to his and his mother’s privacy and constitutional rights. He died in 2007, from heart failure related to his diabetes; the movie implies that the stress of the investigation contributed to worsening his sugar habit. But what many critics and entertainment reporters are concerned about is how the film arrives at its redemption narrative, which rightfully takes on the FBI and media for their roles in intimidating and misrepresenting crime suspects—who, under the law, are supposed to be presumed innocent until proven guilty—but does so at the expense of a character who is, like Jewell, based on a real person who died too soon.

In a way, I understand why the actress and director Olivia Wilde is defending her character, a very fictionalized version of Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporter Kathy Scruggs, who represents the worst of media misconduct for the filmmakers, including Eastwood and screenwriter Billy Ray. Wilde told The Hollywood Reporter that she thinks “people have a hard time accepting sexuality in female characters without allowing it to entirely define that character.”

If you squint, the Scruggs Wilde plays could be IDed as the kind of complicated character many female actors strive to play: a messy, dogged, imperfect, scrappy, sometimes bloodthirsty, but, in the end, human and feeling journalist. Still, it’s wild (pun intended) that Wilde would specifically defend the filmmakers’ choice to have Scruggs get the major tip about Jewell’s being a suspect by—it’s heavily implied—fucking an FBI agent (played by an exponentially more arrogant and bloodthirsty Jon Hamm). After her original defense of the character, Wilde claimed on Twitter that “the perspective of the fictional dramatization of the story, as I understood it, was that Kathy, and the FBI agent who leaked false information to her, were in a pre-existing romantic relationship, not a transactional exchange of sex for information.” In the film, Hamm’s character says to Scruggs about the tip, “You couldn’t fuck it out of them, and you can’t fuck it out of me, either” before she puts her hand on his thigh. The agent then whispers Jewell’s name into her ear.

As many have written and reported, not only is there no proof or indication that the real Scruggs used unethical methods of this nature, but the flagrant embellishment does absolutely nothing for the action of the film—and in fact undermines its credibility. The audience is asked to believe not only that Scruggs seduces an FBI agent into leaking information about an early suspect; we’re also asked to believe that this FBI agent is willing to risk his own career and investigation to sleep with Scruggs, who he doesn’t seem to like that much in the first place.

Though unfounded, the exchange is theoretically possible yet troublingly clichéd—it lands like a misogynistic soap-opera plot in the thick of a film that otherwise takes its own logic and morals very seriously. The real Kathy Scruggs—who died in 2001 at the age of 42—was known to dress in short skirts and daring outfits while taking absolutely no shit from anyone, and in the film, Wilde is costumed as Erin Brokovich’s more id-driven counterpart. A thick layer of eyeliner makes her eyes pop, perhaps to give the impression that the Scruggs character is a bit deranged—like all those troubled, ambitious hussies who wear heavy eyeliner, the film seems to say. Even Wilde’s lines are hackneyed, fake journo-speak, delivered with a blustering sensuality that drips with slutty, slightly inebriated sin.

Ray claims that his only embellishment in the film is the redemption of Scruggs, who sees the errors of her ways by the end. Scruggs’ former colleagues at the Journal-Constitution say otherwise, even sharing that she was troubled by what happened with the Jewell story until the end of her life. About the film’s implication that Scruggs traded sex for tips, former AJC reporter Ron Martz told the paper that “[i]f they had actually contacted me it might have ruined their idea of what they wanted the story to be.” Before the film’s release, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution expressly asked Warner Bros. and the filmmakers to include a disclaimer at the start of the film emphasizing that “some events were imagined for dramatic purposes.” In response, Warner Bros. released a statement adamantly declining to do anything of the sort, but not refuting the Journal’s claim that the quid-pro-quo seduction bar scene between Scruggs and the FBI agent is made up. Ultimately, it’s a he said, she said situation where the she is dead.

Scruggs died by overdose after suffering from a prescription drug addiction, which friends believe resulted from her stress over the Jewell case (the coroner was unable to rule whether the death was an accident or suicide). Ray surely found out this information as he embarked on research for the script, and it’s clear that he and Eastwood use that information to spin her character as a tragic, misguided, skanky mess, which is more of a problem for me than the implication that Scruggs made unethical or simply cruel calculations in her role as a journalist. Even if it were to somehow come out that Scruggs did in fact sleep with an agent (a prospect I find highly unlikely, but we shall see), it wouldn’t change the wrongheadedness of how the character is written and portrayed. It’s a shame, because, as Alissa Wilkinson points out in a piece for Vox on the film, Richard Jewell takes pains to point out that the incriminating details about Jewell’s life—from his misdemeanor for impersonating a police officer to his excessive gun and weaponry collection—did not justify the way the FBI and media treated him after Scruggs’ story was published, nor did Jewell’s image as a fat, working-class white man who fit not only the criminal profile but perceived physical profile of someone who might plant a bomb so he can seem like a hero for saving people from it.

The lesson of Richard Jewell is meant to be that appearances, and even circumstances, do not a bad person make. And further, the establishment—from major media outlets, to law enforcement, to the people who hope to be a part of these institutions—is itself not necessarily innocent, not free and clear of wrongdoing because of their standing and prestige. In that vein, Eastwood and Ray ought to welcome the skepticism of critics and audiences alike, who may not only be interested in the question of innocence, but the more universal, more human idea of justice.