Aside from their occasional entertainment value, GOP presidential debates serve to answer one crucial question above all: which of the candidates would do the best job in confronting Barack Obama in a series of fateful televised encounters beginning about one year from today?

After Thursday night’s exchange in Orlando sponsored by Google and Fox News, it’s safe to say that a number of contenders could probably hold their own with the president of the United States, including Rick Santorum, Newt Gingrich, Jon Huntsman, Herman Cain (who seemed especially confident and likeable)—and above all, Mitt Romney, whose improvement as a TV performer since the 2008 campaign demonstrates an encouraging capacity for growth.

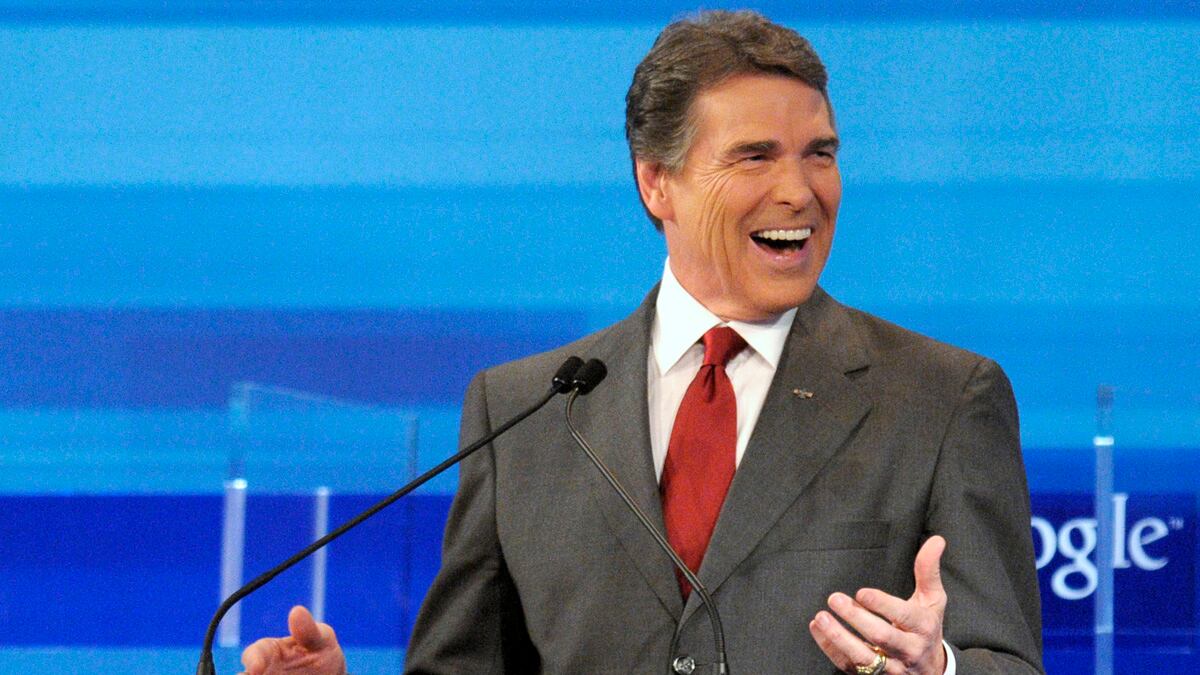

If two hours of questions and answers produced no decisive winner, they did indicate a clear loser. In his third debate appearance Rick Perry looked and sounded ill-prepared, uncertain, dull, vacuous and embarrassingly out of his depth. Even the Texan’s top admirers (and I like him personally and greatly respect his achievements as governor) must cringe at the chilling prospect of a Perry-Obama debate. The take-away message impression from the evening’s encounter showed everyone else getting better (even the crotchety, eccentric uncle-from-the-attic, Ron Paul) while Governor Perry got much worse.

What hurt him most weren’t the tentative, insecure moments when he tried to defend himself against attacks (from Rick Santorum in particular, but also from Michele Bachmann and Mitt Romney) but the feeble, stumbling occasions when he tried to go on offense in his own right against his chief rival, Romney. An obviously canned “gotcha” line intended to slam Romney for switching sides on several major issues (abortion, gun rights, health care) collapsed into such tongue-tied incoherence that it became uncomfortable to watch. Romney deftly responded that he set out his substantive positions clearly and unequivocally in the book he wrote two years ago (No Apology) and that he stood behind every argument and proposal specified in the text. A more nimble debater than Perry might have jumped in to say that “it’s hardly appropriate to congratulate yourself, governor, on your rock-solid convictions just because you’ve now managed to go two years without changing them.” But Perry, looking down at his podium and scribbling notes about something, let the moment (and the opportunity) slide.

In the weeks ahead, Perry’s campaign will begin to lose support from both the right and the center, and he’ll watch the broad coalition he’s tried to assemble begin to gradually disintegrate. After puzzlingly impotent defenses of his own record on in-state tuition for illegal aliens and the state-sponsored HPV vaccine, Perry will see desertions from true Tea Party believers and conviction conservatives on the question of authenticity, while he’ll simultaneously give up backers to Romney on the issue of electability.

The question isn’t whether Perry can sustain his current status as front runner (he can’t). It’s whether he can maintain enough support (for all his money and charm and currently formidable poll numbers) to remain in the race as a viable candidate at all.