Across the globe, billions of people are anxiously awaiting a COVID-19 vaccine, hoping that when they have one everything will be normal again.

But there are also millions who think differently. Surveys in a number of countries show that a substantial percentage of the public don’t want the vaccine, or at least are unsure about taking it. In the US, that figure is as high as 50 percent. A major reason, according to the surveys, is that some people fear possible side effects.

It’s safe to assume it isn’t the prospect of a slight inflammation around the injection point that bothers them, nor a temporary stiffness in their arm—the only modern vaccine side effects on which there is a consensus within the scientific community.

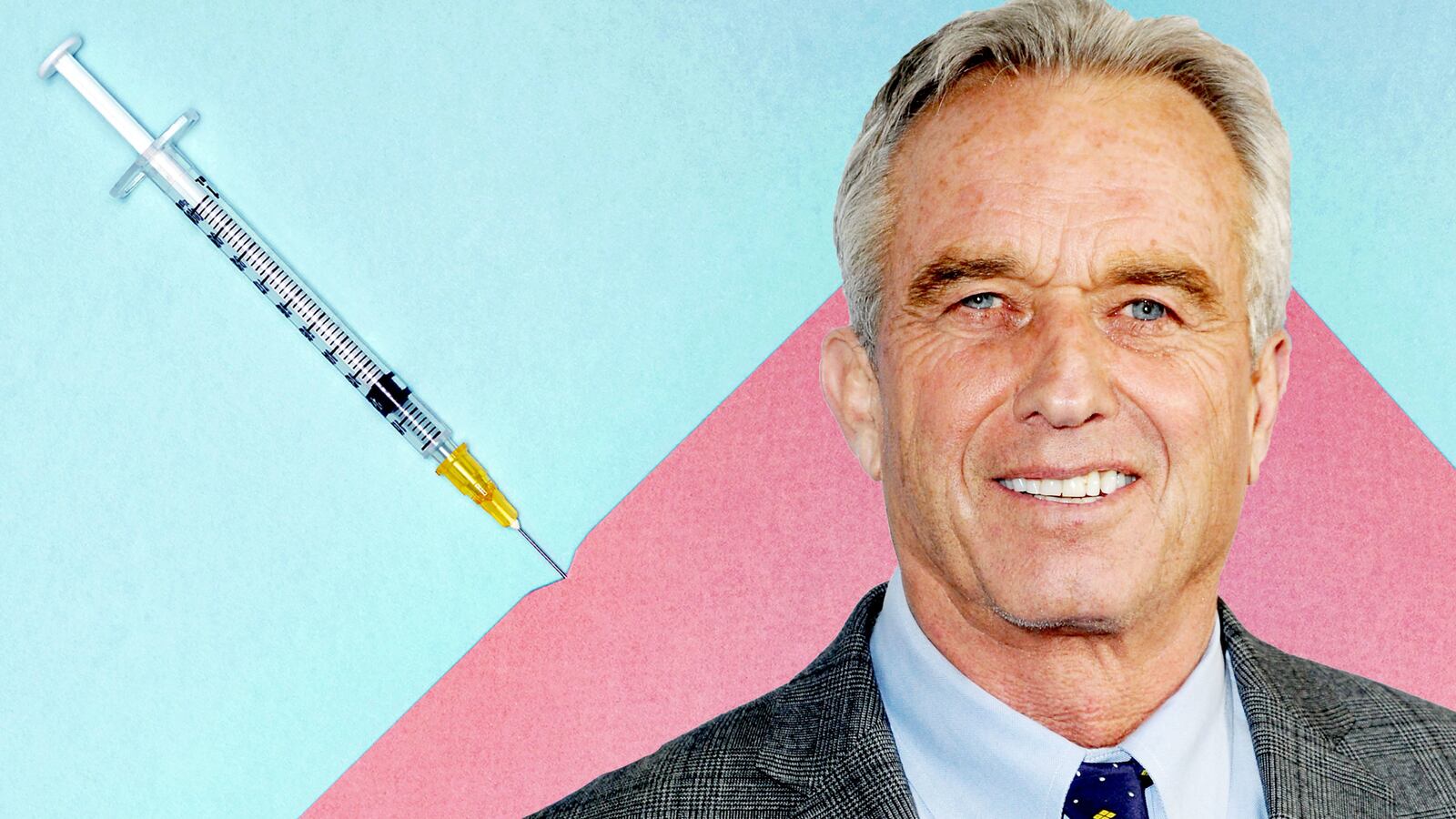

No, straight-up vaccine skepticism—often personified by so-called anti-vaxxers—in the United States and abroad is the problem here. And now Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., perhaps the most infamous of the bunch, is trying to scare people by hyping recently published data on cancer incidence and HPV vaccination in Australia.

That in and of itself isn’t shocking given his history. But he's making a mockery of the data, and compounding larger vaccine skepticism in the midst of a global pandemic, a climate in which vaccine faith—not blind faith, but belief—could prove essential to reining in death and suffering.

A recent article by Kennedy, citing Australian data, says girls there are suffering from cervical cancer—and dying—as a result of having been immunized with the HPV vaccine Gardasil. Could this be the same effect as was seen with oral polio vaccine, perhaps the only documented case wherein a weakened (“attenuated”) virus from a vaccine became virulent and really did cause the disease it was designed to protect against?

Nope.

Gardasil is made in a totally different way. It is inert, which is to say it contains no genetic material from the virus. Kennedy’s sensationalist claim that the vaccine can cause cancer is an attempt to prey on people’s anxieties by making abusive use of statistics.

Gardasil was introduced in Australia 13 years ago, initially given only to girls. Women who are now 25 or 30 years old are likely to have been vaccinated, whereas older women almost certainly were not. Kennedy states that data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, a government agency, show that the rate of cervical cancer has increased by 16 percent in 25-year-olds, and 28 percent in 30-year-olds. This is the basis for the claim that Gardasil causes cancer.

But reaching this conclusion on the basis of these numbers is highly problematic. For one thing, there’s no clear timeframe. When did rates start rising? Immediately after the first girl was vaccinated? That would be absurd. It takes anything from 10 to 30 years for infection with the virus to lead to cancer. If Gardasil were somehow linked to increased rates of cervical cancer, the effect wouldn’t yet be visible.

There’s also the question of which number we look at. The number of cases? The number of cases compared to the Australian population? If we look at the number of new cases divided by the population at risk of cervical cancer (the ‘crude rate’), in 1998 it was 7.0 per 100 000. By 2016, it had fallen to 6.2.

Should this reduction then be attributed to Gardasil? This conclusion, too, is premature. There are too many complicating factors. The newer version of Gardasil is designed to protect against nine types of the HPV virus: the ones most likely to cause cervical cancer, as well as cancer of the anus, vulva, vagina, penis and throat. For a definitive answer to the question of how effective Gardasil is in stopping cancer, we will have to wait a few more years. In the meantime, studies have found strong evidence vaccinations—including in Australia—are reducing HPV infections and genital warts.

Perhaps most important, if Gardasil is responsible for an increase in rates of cervical cancer, this should appear in other countries, too. HPV vaccines have been widely introduced worldwide. One hundred countries have now introduced one of the three HPV vaccines available on the market. Wouldn’t we therefore expect to see rising cervical cancer rates in other countries, especially ones (like Australia) with high rates of vaccination?

We know of no data showing that this is so.

Finally, Kennedy says cervical cancer rates rose in young women who have supposedly been vaccinated, while cervical cancer-related mortality in (unvaccinated) older women decreased. However, comparing the incidence rate in one group with the death rate in another is an illegitimate abuse of statistics.

So the numbers reported by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare do not show that Gardasil cause cervical cancer. Does this mean the vaccine has no side effects? Not necessarily.

There have been reports from a number of countries (including Denmark, Colombia, and Japan) of girls suffering a variety of strange symptoms after HPV vaccination. There has been widespread denial of any link between these symptoms and the vaccine. However, some researchers have noted consistency in the symptoms, attributing them to hard-to-diagnose autoimmune diseases. More research is needed, but the possibility of auto-immune reactions in some specific groups cannot yet be ruled out.

Still, claiming that Gardasil causes cervical cancer is wholly unjustified fearmongering. But just as with a future COVID-19 vaccine, we shouldn’t regard the existence of a vaccine as the ultimate solution to a problem in which politics as much as people’s health is at stake.