A big hunk of space trash is on a collision course with the moon. Some say it’s American, and some say it’s Chinese. Neither side is willing to concede they own the object.

On its own, the object isn’t a threat to anything vital. But experts agree: Not knowing where this rogue junk came from is both a symptom of our increasingly messy activities in space, and a growing problem for the future. The world already struggles to track and identify all the orbital trash out there. And it’s about to get worse as the volume of trash expands.

Bill Gray, an independent space researcher from Bowdoinham, Maine, was the first to notice what appeared to be a derelict second-stage rocket booster, around 40-feet-long, looping 240,000 miles or so from Earth, and on track to slam into the moon on March 4.

At first, Gray figured the booster was part of a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket that launched in 2015 and hauled the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s DSCOVR observation satellite into orbit. That booster has spent the last seven years on an erratic journey around Earth, but nothing too out of the ordinary. “The object had about the brightness we would expect, and had showed up at the expected time and moving in a reasonable orbit,” Gray wrote on his blog.

But then Gray got an email from NASA that changed his mind. The email, from Jon Giorgini at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, reminded Gray that the observation satellite and its leftover rocket stages should all be in roughly the same patch of sky. The booster Gray was tracking was actually nowhere near the satellite it had purportedly lifted into space.

“In hindsight, I should have noticed,” Gray wrote.

A closer look at the data led Gray to a fresh conclusion. The booster is Chinese, he decided.

NASA agrees. “Analysis led by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Center for Near-Earth Object Studies indicates the object expected to impact the far side of the moon March 4 is likely the Chinese Chang’e-5-T1 booster launched in 2014,” the agency told The Daily Beast. “It is not a SpaceX Falcon 9 second stage from a mission in 2015, as previously reported.”

Here’s the problem: The Chinese government insists all the rocket stages from the Chang’e-5-T1 launch—itself a test of hardware and methods for a subsequent lunar sample return mission—are accounted for, and none are about to hit the moon.

“According to China’s monitoring, the upper stage of the Chang’e-5 mission rocket has fallen through the Earth’s atmosphere in a safe manner and burnt up completely,” Wang Wenbin, a Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson, told reporters at a Feb. 21 press conference.

To be clear, Gray’s conclusions are based on telescope surveys by independent astronomy groups. Something is out there, a quarter-million miles away, and it’s heading for the moon. Gray and NASA say it’s Chinese. China says it’s not.

Both sides can back up their claims, to an extent. Telemetry in the minutes following a rocket launch give operators on the ground a good starting point for a given spacecraft or leftover part of a spacecraft.

But in the absence of frequent and detailed observations with powerful telescopes, it’s actually pretty easy to lose track of an object in orbit over time and break the chain of custody. “We can't see these objects all the time,” John Crassidis, a space-debris expert at the State University of New York, told The Daily Beast. “This is due to the limited amount of sensors available to track objects in space, and other factors—for example, telescopes only work at night.”

It’s for those reasons that space agencies tend to log a few direct observations of bigger pieces of space garbage, and then plug those observations into computer models that can project an object’s path around Earth, years into the future.

But those models are imperfect. And they get more imperfect the further in the future you want to look. “If you observe a satellite in one moment and then want its position for the next day, then this is accurate, but if you want that position a year or more in advance, then this is nearly impossible,” Michał Michałowski, an astronomer at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poland who tracks space junk, told The Daily Beast.

One big variable that confounds these models is how the atmosphere affects the motion of satellites and junk. An object might shed parts of itself due to atmospheric drag, changing its trajectory. “Combining these problems means that predicting a position of an object far in the future is more and more difficult,” said Michalowski.

NASA can point to its computer models to justify its conclusion that the moon-bound rocket part is Chinese. But the Chinese space agency can point to any one of the flaws in computer models that Michałowski mentioned to justify its own claim that the rogue booster belongs to someone else.

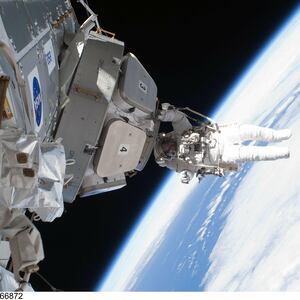

A photo of the SpaceX Falcon 9 launch on February 11, 2015 that took NOAA's DSOCVR spacecraft into orbit. If the rogue booster is SpaceX's, it's from this launch.

NASAThe rogue booster—wherever it came from—isn’t really the problem, however. On March 4, it’ll crash into the lifeless lunar surface in a silent and probably unseen puff of dust. No one’s going to get hurt. Nothing of value is going to get damaged.

But in Earth’s own orbit, there are thousands of valuable satellites, and a steady stream of crewed spacecraft that regularly go into space. Not to mention two entire space stations: the seven-person International Space Station and China’s three-person Tiangong space station.

All of those objects share the space around Earth with more than 23,000 pieces of orbital junk. Any one of those tiny pieces of metal or plastic, traveling thousands of miles per hour, could damage or destroy a satellite or spacecraft or poke holes in a station.

Tracking space debris is a big job with enormous stakes. University labs and government agencies all over the world point radars and telescopes up into space to spot orbital junk, and maintain open databases that anyone can access—and which can give space operators early warning of approaching debris.

When you read about the crew of the ISS fleeing into their attached capsules or hurriedly altering the station’s altitude, it’s usually because there’s some dangerous junk approaching.

That kind of orbital dodging is about to get a lot more urgent, and frequent, as the number of spacecraft and the amount of space debris both grow.

Taking advantage of new, small electronics, more and more companies are developing “mega-constellations” of tiny, inexpensive satellites. Some of the mega-constellations, like Starlink by SpaceX, could include tens of thousands of individual spacecraft.

As those craft age out or break down, each mega-constellation could create thousands of orbital hazards on top of the thousands that already exist. “They pose a unique risk in that there are more objects,” a spokesperson for the Federal Aviation Administration told The Daily Beast.

Anti-satellite missile tests also add to the trash problem. A November test by the Russian military, which destroyed a defunct satellite, spread at least a thousand chunks of metal. Some of the debris passed just 50 feet or so from a Chinese science satellite.

Debris eventually gets dragged back down into the atmosphere by gravity and burns up. But it can take a long time—years or decades, in many cases. Various agencies and private firms are experimenting with maneuverable satellites that can grab onto junk and hurl it toward Earth, speeding up gravity’s process, but that’s an outrageously expensive clean-up method.

The orbital trash situation is likely to get worse before it gets better. “There are too many of them and we don't know precisely where they are, so collisions of satellites and space missions will happen more and more often,” Michałowski said.

As collisions become a bigger issue, it’s increasingly important for the world to hold someone accountable, whether it’s a private company or national space agency. “Where it becomes an interesting problem is when there are indemnification issues, legal issues,” Roger Launius, a space historian, told The Daily Beast. “If your space junk hits something else, you have to take responsibility for it.”

Or perhaps not. If there’s reasonable doubt over who actually produced a given chunk of orbital garbage, pinning blame in courts and embassies could prove difficult. The argument over who sent that booster hurtling toward the moon is a preview of the ambiguity to come.

NASA and Gray are convinced China left that booster in orbit. But Chinese government spokesperson Wang just shrugged off the blame. “We are committed to earnestly safeguarding the long-term sustainability of outer space activities and are ready to have extensive exchanges and cooperation with all sides,” he said.

Beijing practically dared anyone to prove it’s a Chinese booster, apparently knowing full well they can’t.