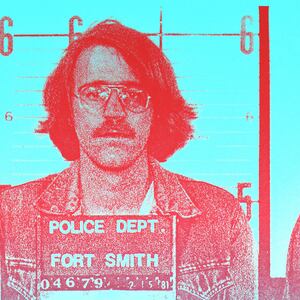

Rolf Kaestel has served 40 years of a life sentence for robbing an Arkansas taco eatery using a toy water gun. Now the 70-year-old inmate will finally be set free.

Last week, the Arkansas parole board voted unanimously to release Kaestel following Gov. Asa Hutchinson’s decision this summer to commute his sentence. As The Daily Beast reported, no one was injured in the 1981 stickup, during which Kaestel snatched $264 from the restaurant’s register before bolting to a getaway car.

When Kaestel exits his prison cell at a Gunnison, Utah, lockup for the final time, the victim of his crime will be waiting to greet him.

Dennis Schluterman, who was a teenage employee of Senor Bob’s Taco Hut in Fort Smith, has long rallied for Kaestel’s freedom. In 2013, he recorded a video message for then-Gov. Mike Beebe outside the state capitol, pleading, “This man has paid the price ten times over, and it’s time—time for you to let him go.”

“He didn’t deserve to die in prison,” Schluterman, 58, told The Daily Beast on Monday.

“I just want him to get out and do good and be able to enjoy a little bit of the rest of his life,” Schluterman said. “At 70 years old, these days, who knows.”

Filmmaker Kelly Duda, another longtime advocate, will join Schluterman outside the penitentiary walls. “This day is long overdue,” Duda said. “Dennis and I look forward to greeting Rolf outside those gates and to us all enjoying ice cream together.”

According to Duda and Schluterman, Kaestel is expected to be released around Oct. 12. While the parole board confirmed Monday that it granted Kaestel’s release, officials didn’t return messages seeking comment on when he’d walk free.

Duda first met Kaestel in 1999, when he interviewed him for 90 minutes as part of his documentary on a blood bank scandal within the Arkansas prison system. Ever since, Duda has staunchly agitated on Kaestel’s behalf and recently garnered support from music executive and justice crusader Jason Flom, CNN commentator Van Jones, actress-activist Rose McGowan and GOP fundraiser Jack Oliver.

At the time of his arrest, Kaestel was a small-time crook who was traveling across the country with a band of young drifters who’d run out of money. As the group traveled through Arkansas on a Sunday night, Kaestel spotted Senor Bob’s and suggested they rob the restaurant. Kaestel, then 29, and a young accomplice entered the store and pretended to peruse the menu just as Schluterman came out to greet them.

Kaestel then flashed the butt of a toy pistol and said, “You see that,” before swiping cash from the till. The men fled, and cops soon found their crew at a gas station across from state troopers’ headquarters. (The alleged accomplices avoided charges in exchange for testifying against Kaestel, who represented himself at trial.)

In Arkansas, juries handed down both verdict and punishment. Kaestel’s peers convicted him of aggravated robbery and imposed the maximum sentence after former prosecutor Ron Fields urged them to do so, court transcripts show.

“How many times have you heard in the past people say, ‘I wonder why everybody is being so lenient with these type people,’” Fields told jurors, according to court records. “Well, ladies and gentlemen, I’m asking you not to be lenient.”

Under state law, prisoners serving life aren’t eligible for parole unless the governor commutes their sentence. The parole board, however, first reviews inmates’ clemency applications and makes recommendations to the governor, who has the final say.

The Arkansas board recommended Kaestel’s clemency three times in the last decade, including last November. “Forty years and counting has certainly been a heavy price, wouldn’t you say?” Kaestel said in correspondence with The Daily Beast. “I sometimes wonder how it would have turned out had things been different, but that’s actually silly to do.”

On Monday, Fields told The Daily Beast that he’s “comfortable” with the parole board’s ruling because the panel falls under the administration of Hutchinson, who denied Kaestel clemency in 2015. (Fields was a law school buddy of Hutchinson and, in the early 2000s, worked under him at the Drug Enforcement Agency and Department of Homeland Security.)

“I was surprised he stayed down there as long as he did,” Fields said of Kaestel’s lengthy sentence. “There must have been some warning signs to hold him as long as they did. … But he’s substantially older now.”

“Time fixes us all,” Fields concluded.

Kaestel was a model prisoner for much of his incarceration, one who worked as a paralegal for a Little Rock law firm and took years’ worth of college courses. He also taught classes to other prisoners and worked in the Gunnison facility’s library.

His decades-long fight for clemency was a curiosity to all who knew him. Advocates wondered why the state insisted on keeping an aging, reformed inmate locked up to the tune of $20,000 a year and argued the punishment didn’t fit the crime. Murderers and rapists have gotten out in less time, they said.

“As far as I’m concerned, they [the state] just said he’s going to die and rot in prison and he doesn’t deserve to. Period,” one educator who worked with Kaestel told us earlier this year.

Duda suggests that Kaestel was a political prisoner for serving as whistleblower in his 2005 documentary Factor 8, though Kaestel told us in a letter: “I cannot convince myself that someone may be pulling strings behind the scenes to vindictively keep me locked up.”

The film focused on the Arkansas prison system’s 1980s and ’90s era blood bank—the only form of income for inmates who donated plasma. The program was operated by fellow prisoners, who supposedly failed to screen for diseases like HIV and Hepatitis C. Corrections officials then shipped the bad blood to brokers in Canada and abroad, infecting thousands of people, some fatally.

Soon after Kaestel spoke to Duda on camera, corrections officials transferred him to Utah, citing Kaestel’s alleged “noncompliance with the Arkansas system.”

“If somebody had told me at that time that 20-plus years later this would be going on, I wouldn’t have believed them,” Duda said of his activism for Kaestel over the years. “But I felt responsible in trying to help the world see him and his plight.”

“It took a social justice village to free Rolf,” Duda continued. “As grateful as I am for that, it shouldn’t have been necessary.”