When Ron DeSantis took a trip to the Texas-Mexico border on Monday, his campaign had the good sense to take and promote a photo of the Florida governor in front of a helicopter for an image ready-made for a political ad.

But that photo—and the accompanying tweet—may end up costing DeSantis much more than he bargained for.

That’s because the helicopter DeSantis posed in front of is property of the Texas Department of Public Safety, according to Federal Aviation Administration records. And experts say his use of Texas government resources for his own political purposes appears to constitute a campaign finance violation.

His trip to the border is now raising legal questions about who paid for the junket and why the campaign was granted access to Texas government property to promote a political event in the first place.

The questions notably apply on the Texas side as well, where state law bans the use of public resources in support of candidates for political office.

During the trip, DeSantis was given an aerial tour of the border, matching public flight records for that same helicopter. (An NBC News correspondent covering the trip also took a helicopter tour, which his video shows was piloted by a Texas law enforcement agent.)

DeSantis was also given a boat ride between the banks of the Rio Grande, where he observed migrants attempting to cross the river being “blocked by TX after crossing,” according to Fox News’ Bill Melugin, who accompanied the Florida arch-conservative for both the aerial and riparian tours.

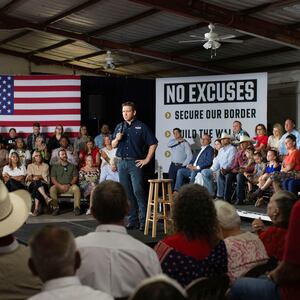

After the border tour, DeSantis gave a lengthy campaign speech detailing his immigration platform, where he was introduced by House Freedom Caucus member Rep. Chip Roy (R-TX), who has already endorsed DeSantis.

The speech was clearly a campaign event, with the Florida governor standing in front of a banner that implored the audience to text “FREEDOM” to a campaign number to receive political updates on DeSantis.

It’s not immediately clear how or whether the campaign compensated the Texas government for the vehicles, man hours, operational costs, or other expenses associated with DeSantis’ border tour. Questions sent to Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s office, the Texas DPS, and the DeSantis campaign went unanswered.

But legal experts expressed concern about the funding.

Saurav Ghosh, director of federal campaign finance reform at the Campaign Legal Center, told The Daily Beast that if DeSantis used taxpayer resources to advance his candidacy, then “his campaign has to reimburse the state of Texas for the cost, or else he’s received an unreported and likely excessive in-kind contribution.”

“If he misuses public resources to run for president, it’s an abuse of his position and a likely violation of federal campaign finance laws,” Ghosh said, noting that the immigration policy announcement was a major moment for the campaign.

Jordan Libowitz, communications director for Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, agreed with Ghosh, noting that state or federal resources “should not be used to help a candidate for partisan political office.”

Libowitz added that even if the campaign reimbursed the Texas government, that alone would still not explain how his campaign got access to a state vehicle.

Those decisions to give DeSantis a tour of the border for political purposes would also appear to be a wild departure from any previous campaign.

A review of Federal Election Commission filings shows that federal political committees have made only four payments to Texas DPS—the agency responsible for statewide law enforcement—the largest of which was $10.00)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://docquery.fec.gov/cgi-bin/fecimg/?14970724412__;!!LsXw!SMXXbie7kbUtkobve_iE2dsIUyQGQtFaf3Wau7qM9YOfoGRM9BiUUGAR-06pt_Kj_vQGOOLsDjnDfQ1hCGd2x6R1-aczjgZLEQ_CZw$">$10.00 in 2014. No federal committee appears to have paid the state of Texas for event or fundraising services in any recent election, according to an analysis of all FEC disbursements reported to Texas entities in amounts of $1,000 or more for the last five election cycles.

While DeSantis could theoretically duck repercussions by simply reimbursing the state of Texas, the arrangement is much harder to clear up on the Texas side, where state law restricts the use of public resources for political activity.

Those statutes bar any state agency from using “any money under its control, including appropriated money,” to fund “or otherwise support” a candidate for state or federal office. The ban on political activity includes “the direct or indirect employment” of state workers or officials, specifying that those employees “may not use a state-owned or state-leased motor vehicle” for such purposes—which would seem to include the candidate’s use of the DPS helicopter.

Texas law also prohibits state employees from using their “authority or influence” in campaign activity—and it bans “the use of a program administered by the state agency of which the person is an officer or employee” to affect an election “or to achieve any other political purpose.”

DeSantis and his allies in the Texas state government can claim the border trip was official business, but his campaign’s decision to post a photo of the Florida governor on Twitter from a campaign account make that argument harder. As does holding a political speech, where DeSantis railed against the border policies of President Joe Biden and GOP frontrunner Donald Trump. (DeSantis’ campaign also promoted his speech with a video decrying the “invasion” of undocumented immigrants.)

While the ultimate funding of the junket is still unclear, records suggest that the border trip was campaign-specific and not connected to DeSantis’ official capacity as governor.

The governor’s office reported no scheduled events that day, according to a Monday press release. And flight records show that DeSantis appears to have traveled to Texas from Tallahassee on a chartered plane, as opposed to traveling by a donor’s private jet or a state-owned plane—modes of transportation DeSantis has tapped in the past.

DeSantis has previously taken chartered planes on official state business, including a trip circumnavigating the globe earlier this year, as Politico reported. That flight was bankrolled by an opaque public-private Florida entity that reaps significant funding from private donations, according to Politico. And the Florida legislature quickly took steps to block the public from knowing key details about DeSantis’ travel, including who’s paying.

In May, The New York Times reported that DeSantis often tapped wealthy donors to “ferry him around the country” as he conspicuously ramped up his national profile. Several donors were known DeSantis supporters, some with business interests involving the Florida government. Other backers, however, kept their names hidden behind a new nonprofit that hosted events on his book tour, which doubled as a shadow campaign ahead of his glitch-rich official announcement last month. Earlier this month, The Washington Post reported that a wealthy donor and Miami developer had also provided flights for DeSantis, as well as for his wife, Casey DeSantis.

With this most recent case, however, the Texas tag-team evokes another scandal.

Last year, DeSantis—who last month deployed Florida National Guard troops to the Texas border—drew widespread condemnation when he flew a group of migrants out of Texas only to deplane them in Martha’s Vineyard, the Massachusetts island community fabled as a haven for wealthy liberals. According to reports at the time, the Florida state government collaborated with a third-party vendor to transport the asylum-seekers.

Earlier this month, the Bexar County sheriff in Texas recommended criminal charges in connection to that stunt, which had already invited multiple lawsuits from the Venezuelan migrants, in addition to prompting a Treasury Department investigation.

On June 5, the Baxter County sheriff filed multiple charges of unlawful restraint with the local district attorney’s office, including felony counts, though the targets of those charges have not been revealed.

That same day, the Florida government left another group of migrants in Sacramento after they boarded a state-chartered jet in Texas. A spokesperson for the Florida agency behind the California operation claimed that the flights were voluntary.

Either way, DeSantis’ use of Texas resources for his campaign is just the latest example of the Florida governor stretching good government rules for his political benefit.

DeSantis currently faces a lawsuit over his use of Florida money to transport migrants around the country. He’s targeted Florida’s notoriously strong sunshine laws to make it easier to sue the media for defamation, and the executive director of the Florida Center for Government Accountability, Barbara Petersen, told The Guardian it would be “virtually impossible to hold this governor accountable” without access to his travel records.

Additionally, DeSantis faces a complaint from Campaign Legal Center over the transfer of $80 million from a state PAC to his federal PAC, Never Back Down, while also drawing criticism that DeSantis administration officials reportedly pressured lobbyists into giving donations.