“I’m in Hollywood, baby, where movie stars like me belong,” says Ron Perlman.

Due to the ongoing novel coronavirus pandemic, Perlman is sequestered in Tinseltown and speaking to me by phone about his new film, Clover, available now on demand. In the film, produced and directed by Jon Abrahams, he plays a menacing crime boss whose opening monologue concerning the primal nature of man gamely sets the stage for the ensuing action.

Perlman, 69, overcame weight issues and a lower-middle-class upbringing in Washington Heights—his father was a TV repairman—to become one of the most celebrated character actors alive. He has dazzled with scene-stealing turns in Guillermo del Toro’s Hellboy films, Drive, The City of Lost Children, and Sons of Anarchy, among others.

He’s also emerged as one of the most outspoken Hollywood critics of President Donald Trump and his administration. “Those of us who have a voice are going to make sure he never forgets that he’s a danger to humanity,” he tells me.

Over the course of our very amusing conversation, we discussed the way the Trump administration is handling the pandemic, his affinity for tough Jews, and the time he pissed on his hand before shaking Harvey Weinstein’s to teach the monstrous ex-Hollywood mogul a lesson.

We’re both New Yorkers. How are you handling this coronavirus madness?

Well, I’m personally doing fine. I’m one of the lucky ones that has had a decent run and not living paycheck to paycheck like 90-some-odd percent of the people in this world. For them I worry. I’ve got a daughter and a wife in New York, and my wife’s got a big family in New York, so I worry about them a lot. But me personally, I’m keeping the faith, staying to myself, only going out for essentials, and trying to balance the insanity of how this is being handled by our leadership and the tragedy of how it’s affecting everybody on the planet.

About that lack of leadership, from downplaying the pandemic, to politicizing it by blaming Democrats, to repeatedly delivering dangerous misinformation (like how we’ll be back open by Easter), to shipping 17.8 tons of medical supplies to China in February right before the pandemic hit us, it’s been a pretty awful ride for Trump even by his standards.

There’s a huge segment of the population that’s anticipated from the get-go that this was some sort of horrible, aberrative nightmare that he managed to squeak his way into power, and it’s Nostradamus on steroids—having the village idiot ascend to the highest office in the land. We all knew there was going to come a test, and he was kind of lucky in that in his first three years he never had to deal with the kind of leadership that a situation like this demands. Now that he’s been caught with his pants down, we’re seeing the stark reality of the consequences of living in a country that doesn’t always vote in their best interest. The price that’s being paid for that is nothing short of tragic.

There’s an added layer of strangeness because he’s from New York City, and yet he’s not supplying his own city with the medical supplies—masks, ventilators—that they need, costing thousands of lives in the process.

He has no city. He has no country. He has no core. He has no center. All he is is a flailing compendium of needs for attention, for wealth. The word “narcissistic” is overused so I tend not to use it, but you know, that’s what it is. He has no country, he has no city, he has no friends. He has people who he benefits, and so he’s been allowed to stay in the lofty position that he’s in for the sake of a few thousand people who are greatly benefiting from all of his excesses, but the tab is on us—as it always has been with Trump. The tab has always been on us.

And just a thing about New York: If I make it to next week I’ll be 70. As a New Yorker, as somebody who grew up lower-middle-class, a lifelong Democrat, and somebody who generally looks at the world through the lens of the greater good—and lifting up the less fortunate—he’s always been a fuckin’ joke. I mean, a complete fuckin’ joke. His ascension to the position that he’s in right now is an indictment on our society, and it’s the worst kind of indictment because of the suffering that is now being exacerbated—and you cannot exaggerate the amount of lost lives that are happening basically because of his narcissism, and him looking at this as a PR problem and a threat to his ability to hold power. That’s all he’s ever looked at this as. There’s not one ounce of compassion for suffering; there never has been, there never will be. There’s not one ounce of empathy that it takes for a leader to take himself completely out of a situation and act in the interest of the greater good. There never has been one shred of it and there never will be, and for anyone to expect that of him, and to talk about him as the “leader” of this country, is an insult to leadership.

Your mother worked for the Department of Health too, right?

She did. She didn’t start working from the city until her kids were grown, so she was in her forties when she went back to work, but she worked in the tuberculosis department—which might seem like an oxymoron, since it hasn’t been on the front of people’s lobes for a while, but that’s where she found herself. Mom passed away last year at 97, but everybody in my wife’s family worked in the system taking care of other people. I have a brother-in-law who could have made a gazillion dollars practicing law but he worked for the City of New York and made five figures, tops.

My wife’s mom was a health worker. Everybody was there in the service of others; there was nobody there that was longing for wealth, or acclaim. It was folks figuring out what they could do to help out, so that’s a philosophy that’s ingrained in me, and it’s being shaken to its core by how little regard one entire party of our country, and the 40 percent that supports them, are showing when they’re all going to be touched by this, and they’re all going to need a health worker who forgets about their own family and themselves, and goes in to work and puts themselves in harm’s way. They have no ability to understand the connection of how desperately those people need to be admired, nurtured, loved, and given every single thing they need to make their lives less risky.

It’s also thrown into stark relief what makes an “essential” worker, and how these jobs are compensated versus other jobs.

What’s happened with the Trump administration is it’s shown in stark relief all of the cracks in what we like to think as “exceptional” America. It’s “exceptional” in a lot of ways, but all those ways seem to have completely lost their meaning and value. We’re an autocracy now. We have a government that’s governing by fiat, and they’re protected by a Justice Department that seems to have been waiting in the wings since the death of Hitler to be able to just have their way with the law, and fuck the Constitution, and fuck every bit of spirit that the Constitution represented. We’re not approaching that—we’re there now—and luckily we have one party that’s kind of speaking for the Constitution and holding them in somewhat of a check, but if they had their way—the McConnells, Barrs, and Trumps—we would be up shit’s creek.

Let’s talk a bit about Clover.

Why? I’m having so much fun! [Laughs]

I’m sure we’ll get back to the current madness eventually. But with Clover, I really enjoyed your juicy monologue at the beginning. It reminded me a bit of William Hurt in A History of Violence.

What attracted me to the character is I got to play the entire role in one day, which suits my concentration span to a T. I also got to play a character that had so much perversity to him in his wiring, and the saliva starts flowing and you spit out this performance that’s loaded with idiosyncrasy and sick, twisted perversity. In a short period of time, you’re describing a character that’s megalomaniacal and judge, jury, executioner—all wrapped up into one. Plus, you set off the next two hours of what the audience gets to see, because of all those excesses. So it was a phenomenal offer I couldn’t refuse.

Are you drawn to these menacing characters or do they choose you?

It’s a two-way street. In the last 20 years, these great roles have been finding me, and all I do is basically recognize them and go, “Oh my God, I can have a lot of fun with this guy.” But it took a long time for the world to start sending me things that were in my wheelhouse. I think I was 50 before that really, really started to happen. Originally it was Jean-Jacques Annaud, then Guillermo del Toro, then Jean-Pierre Jeunet came along later on. I did multiple jobs for all three of those guys, and they were sustaining me—artistically anyway—up until I turned 50, and then all of a sudden, either my competition started dying off or they left the business, but I started getting these juicy offers. I mean, I was 53 when we did the first Hellboy, and I was 57 when we did Sons of Anarchy. A lot of the stuff I’m really proud of on the résumé came after 50.

Ron Perlman in Clover.

Freestyle ReleasingOne really awesome story is the time you pissed on your hand prior to shaking Harvey Weinstein’s. I’m curious when that happened and what gave you the idea to do that?

I think it was around 2001, because I was making Blade II with Guillermo in Prague and had a few days off, so I ran down to the Cannes Film Festival. That’s where it happened. I never really had a relationship with Harvey but I wanted to show up to one of his charity events, and when I got on the phone with him to request a ticket, he just acted like a fuckin’ piece-of-shit pig, like, “Who are you to ask me? Do you know who I am?” He thought I was returning the Revlon guy’s phone call [Ron Perelman], which is why he returned my phone call in the first place, and when he realized I was just the actor he just went off on me.

I said to him, “Well, it’s OK, Harvey, I managed to get a ticket between the time I called you and now, so I’ll be there tonight.” And he said, “Oh, you’ll be there? Well, make sure you shake my hand out of respect.” And I said, “Oh yeah, Harvey, I sure will.” And that’s the genesis of that story.

And he didn’t notice, I gather?

Well, he knew it was clammy… I’m hoping he read the tweet where I finally outed myself.

The infamous piss-shake. Had you ever used that move before or was this a one-time deployment?

That was a one-off. But there aren’t many people that deserve that move like Harvey Weinstein did.

You know, my father’s Jewish and from New York, and it’s interesting because you as an actor, you’ve managed to transcend a lot of ugly stereotypes about Jews on screen by playing these imposing badasses. Is that something that’s been in the back of your mind as well?

I’ve always been attracted to tough Jews. My very, very best friend—in ’94 I think he passed—his name was Burton Levy, and he once walked into a bar in Yonkers. He’s the kind of guy who didn’t live small, and he had pissed somebody off in the bar. He walked in to getting punched in the side of the head by one guy and having a barstool get slammed over his head, and as he was going to his knee from the first blindsided punch, the barstool to the head kind of woke him up, and I watched him take out 25 guys in this bar, single-handedly. He was a pretty tough Jew. I’ve known a lot of tough Jews, and they fascinate me. I don’t have a lot of memories of fisticuffs, personally. You know, I’ve been in a couple of fights.

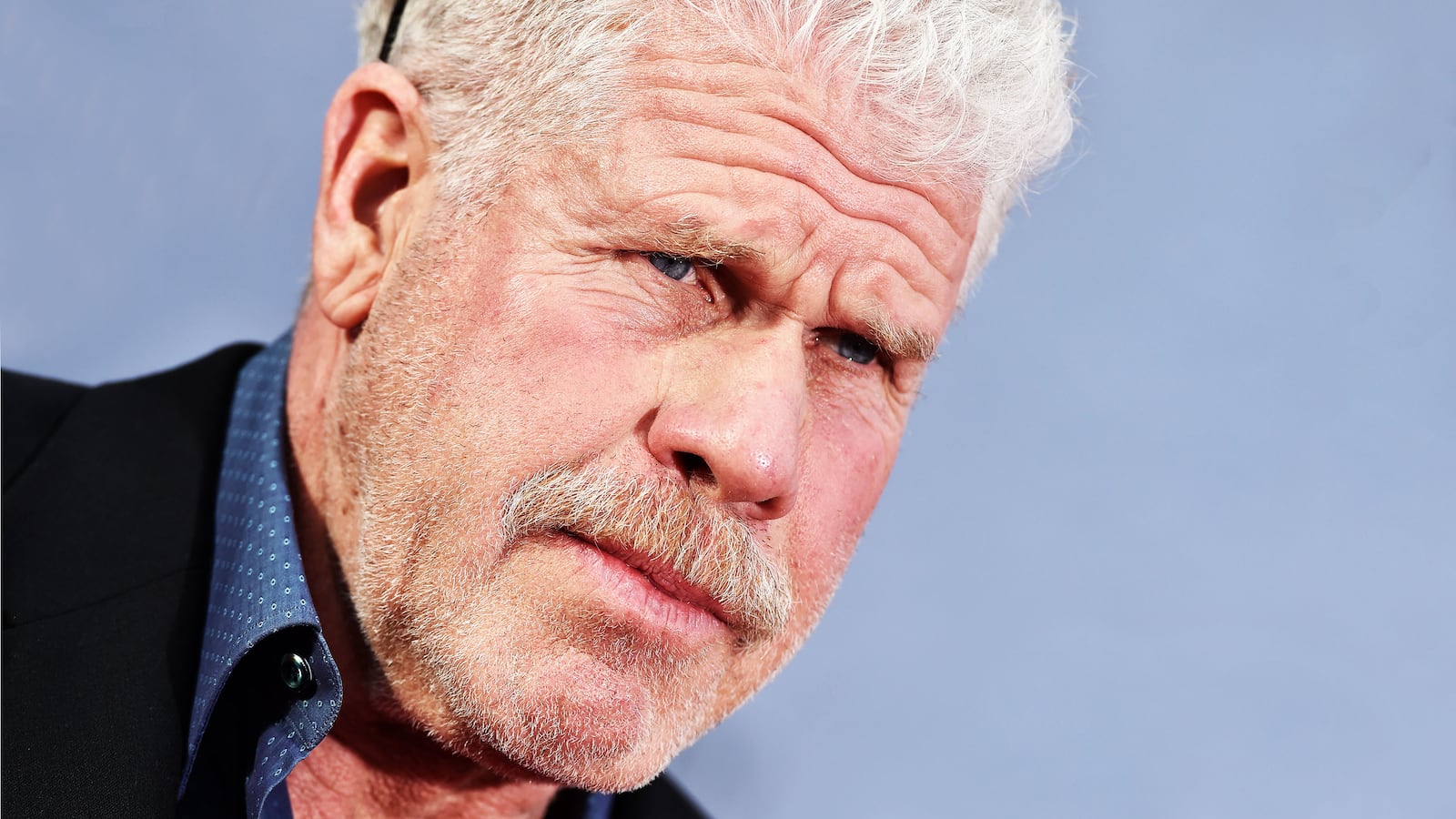

Ron Perlman attends the 30th anniversary screening of When Harry Met Sally at the 2019 10th Annual TCM Classic Film Festival on April 11, 2019, in Hollywood, California.

Emma McIntyre/GettyYou’re not necessarily someone people want to fuck with.

[Laughs] I’ve been pretty lucky with that. But you know, that kind of fearlessness that it takes to be tough is a fascinating quality for me. And I don’t think it’s because I’m Jewish or anything like that, it’s just a coincidence—but it’s a happy coincidence, because I’ve been able to channel and project that in my career.

I loved the Hellboy films you did with Guillermo, and I tried watching the reboot on cable but shut it off after a few minutes. Was it weird that that got made, and have you seen it?

I have not seen it. It was not weird that it got made; it was no big surprise. People thought there was money to be made, so they just went ahead with trying to exploit a brand without realizing what they were up against. That brand had already been exposed in a way that was very endearing to people. You’re already behind the 8-ball, so you better make a fuckin’ great picture—something that makes people forget about the originals—and like I said I haven’t seen it, but from what I understand… don’t get me started on reboots and remakes and shit, because it’s a whole other conversation and I can get into a lot of trouble.

I read that you grew up on the heavier side and were bullied a bit. How bad did it get, and how did you manage to so defiantly overcome it and morph into this big, burly action hero?

A lot of kids grow up heavy. In my case, it was just the springboard of an incredibly low self-esteem. When I finally found acting, and embodied other personalities and characters for a few moments in time to get my mind off of how shitty I felt about me, it gave me a therapeutic ability to feel good about the people I was playing, and therefore have that somehow rebound onto me. It was like an aphrodisiac—like a drug, playing other characters—and it sustained me until my forties, playing these phenomenally interesting characters and almost become interesting because of that, even though I was fighting this bad self-image. In my forties I started liking myself finally, and coincidentally, that’s when the tough-guy roles started coming in. So I got a chance to use acting out of need in the first half of my career, and no longer had a need for it but an incredible love for it in the second half. And for that I’m grateful.