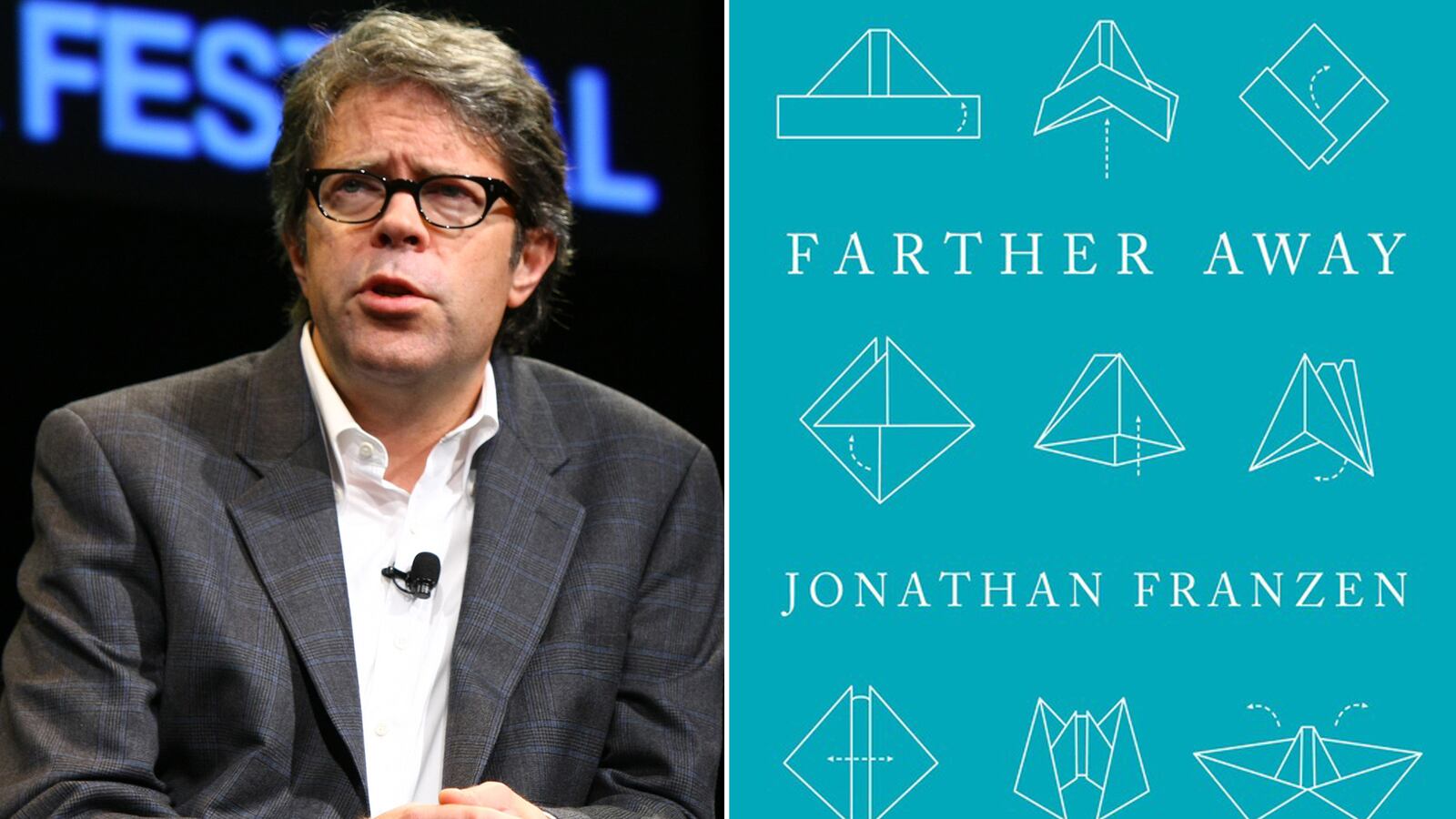

In the title essay of his new collection, Farther Away, Jonathan Franzen travels to a tiny, uninhabited volcanic island in the South Pacific to come to grips with the death of his close friend, David Foster Wallace. Along with a GPS tracker, satellite phone, and a few scant traces of the “technocapitalist” culture he loves to rail about, he brings with him a copy of Robinson Crusoe—which Defoe apparently based on a real-life survivor who once inhabited the very same rock—intending to practice a little of the hero’s rugged individualism himself. Thought-provoking and metaphorical hardship ensues, and, along the way, he is able to scatter’s some of his friend’s ashes, muse on the history of the modern novel, and nearly get blown off a rocky cliff side.

I thought about reading this book in my own ascetic redoubt, on the craggy shelf of some perilous mountain, maybe haunted by cannibals, with only a flat soccer ball to keep me company. But I don’t camp. My idea of “roughing it” is a Radisson with a meager mini bar and I get cranky when Whole Foods doesn’t have its entire grazing menu available when I visit. So I went the other way with it. I brought Franzen’s book with me to my idea of paradise, a sanctuary from the cruel elements of Manhattan Island.

On Easter weekend, I checked into the Bowery Hotel.

While I read about the animal-rights activist Franzen huddled in the fog and rain, I steeped myself in the finest essential oils—“tested only on actresses,” according to the label, “never on animals.” While he risked life and limb to do some bird-watching of the Audubon variety, I sat in the lobby with a cup of tea, doing some bird-watching of the Avedon variety. While I read him ranting about the modern abuses to our privacy wrought by evil devices, I eavesdropped on Aziz Ansari breakfasting with his family. By the time he’d gotten to his saga of illegal bird poaching in Cyprus, I was unhappily eschewing the chicken to go for granola.

Like Franzen (or at least the Franzen trapped in the amber of his essays), I live without a TV. So, not surprisingly, soon after checking in, I submitted to its siren call and half-watched the Masters while reading him on the ecological abomination of golf. But after slipping into the Lethe of entertainment for a short while, and being assaulted by commercial breaks, I was ready to run off and join him in any ultima Thule of his choosing. Franzen, whose first collection of essays was called How to Be Alone, writes incredibly well about isolation, depression, the banality and diminishing returns of entertainment, and especially about boredom. Like his Gen-X contemporaries, including Wallace, Franzen sees our modern ennui as the big bogeyman of our time. “If boredom is the soil in which the seeds of addiction sprout,” he writes, “and the teleology of suicidality are the same as those of addiction, it seems fair to say that David died of boredom.”

After the opening essay, a commencement address given to the Kenyon College Class of 2011, entitled “Pain Won’t Kill You,” we come to the essay concerning Wallace’s struggles. Along with a later piece, given as a eulogy at his friend’s memorial, this is the most intimate, most complete, and most devastating reflection on Wallace’s suicide. Franzen waited, while the entire Internet seemed to bloom into a million-petaled bouquet for his friend, put it off, finished Freedom, went on a book tour, avoided it, and then delivered the final word: “Throughout that year, the David whom I knew well and loved immoderately was struggling to build a more secure foundation for his work and his life, contending with heartbreaking levels of anxiety and pain, while the David whom I knew less well, but still well enough to have always disliked and distrusted, was methodically plotting his own destruction and his revenge on those who loved him.”

Seen beside the two luminescent elegies, the rest of the essays in the collection appear in long shadows. To use a Franzen formulation: his entry on the economy and ecology of modern China (“The Chinese Puffin”) is a paragon of the Apollonian form, but hasn’t the Dionysian heat of his writing about Wallace. These less animated, if no less personal, adventures, to China, as well as Malta and Cyprus, sag in comparison. Franzen can sound like an old fogey—as he well admits, when bristling about people on their cell phones—even when it is in the service of a greater point. But he is nothing if not powerfully earnest, and it is fascinating to read him struggling, baldly, palpably, with both his own personal problems and the great topics of our time. A lecture, On Autobiographical Fiction, begins reading just that way, as a lecture, but shrugs off its formal ballast to wander into a poetic moment inter familia—Franzen’s métier—as his dying mother gives him permission to live for himself, not for her, not for anyone else. From a remembered road trip with his parents springs some of the most arresting writing you’ll ever (“Then a wall of rain hit our windshield with a roar like deep-fry.”).

While the Wallace bits are undoubtedly the stars of this show, the most exciting moments are when Franzen writes about fiction. “Reading about reading,” as he wrote in How to Be Alone, “makes you want to run out and do it.” And throughout this book I was chomping at the bit to read more, more, more. Franzen may be among the most recognizable novelists in the world at the moment—at least he is the first writer in over a decade to appear on the cover of Time magazine—but, as we are beginning to discover in his essays, he is certainly among the form’s most fervent evangelists. Like Chris Rock, in Jerry Seinfeld’s Comedian, gushing, awe-stricken at having seen Bill Cosby doing stand-up, Franzen is effusive in his praise of the writers he loves.

“This is not a golfer on a practice tee,” he writes on the topic of the great Alice Munro, not even bothering to contain his giddiness. “This is a gymnast in a plain black leotard, alone on a bare floor, outperforming all the novelists with their flashy costumes and whips and elephants and tigers.” His raving, about James Purdy, the Swedish thriller The Laughing Policeman, or Donald Antrim, are impossibly infectious. With my image of him—aided, no doubt, by Time and the media-cycle profiles in a zillion other outlets—as the scruffy suburban bobo, I might not have been totally surprised to discover his passion for The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit. But to read him writing about his passion for reading it, his old favorite Desperate Characters, or Dostoevsky, is like listening to Peyton Manning narrate an NFL film documentary on the greatest quarterbacks in history. He is a fan of the game. And, ironic as it may be to read the defender of fiction, during a burgeoning golden age of nonfiction, writing essays to defend his craft, it is inspiring.

Like I’d died and gone to heaven, in fact. Though on the third day I had to rise again.