The District of Columbia courts recently disbarred disgraced lawyer Rudy Giuliani for his making repeated false statements in his efforts to overturn the 2020 election in the courts. This followed a decision from July of this year disbarring him in New York as well. These after-the-fact actions have come nearly four years after the events that justify this punishment. Some might hope that such discipline might deter other lawyers from seeking to take similarly improper actions to challenge the results of the 2024 election.

But our legal system does not have to just wait around for similar events to unfold and only punish such actions afterwards. Courts can and should take preemptive measures to avoid the same sort of improper behavior from repeating itself after the polls close in November. It is said that a lie gets halfway around the world before the truth gets its boots on, but judges can start to insurrection-proof their courtrooms now in order to prevent history from repeating itself.

In the wake of the 2020 election, lawyers in dozens of courtrooms across the country, including Giuliani, sought to overturn the results of the vote and attempted to use the legal system to derail the peaceful transition of power by making wild and baseless claims about voter fraud. And, no, those cases were not dismissed “on a technicality,” as Donald Trump claimed in his debate with Vice President Harris earlier in the month.

Most were thrown out simply for the failure of the lawyers to present any evidence of fraud in the election. With no proof of fraud, they chose instead to make specious and fantastical claims about home security systems switching votes and dead Venezuelan political leaders somehow changing the results of the election from the grave.

When those efforts in the courts failed, as they should have, some of those same lawyers spoke to the crowd on Jan. 6 and encouraged them to take action, including one of them, Giuliani again, demanding “trial by combat.” He, like some of the other lawyers who participated in this campaign, have been disbarred, or will soon likely be disbarred, with Giuliani having that occur in his home state of New York and now the District of Columbia. Giuliani and these other lawyers failed to uphold their obligations to act in accordance with the rule of law and professional ethics. Such punishments only occurred after the fact though.

As we enter another national election season, courts need not stand by and rely solely on the ability to punish lawyers for misconduct after it happens. Our legal system can take steps now to insurrection-proof its courtrooms in a way that discourages other lawyers from engaging in such behavior before it unfolds.

Giuliani exits U.S. District Court after attending a hearing in a defamation suit related to the 2020 election results, May 19, 2023.

Leah Millis/ReutersThe disciplinary machinery that presently permits courts and other regulators to punish lawyers for misconduct usually only gets up and running after lawyers engage in misbehavior. And when lawyers file frivolous cases, the courts presiding over such cases can issue sanctions against lawyers after the fact.

Our criminal and civil justice systems generally work this way. We are not in a world like that envisioned in Minority Report, where precogs can predict crime before it happens. And that’s a good thing. But our system of justice also works slowly, and even efforts to address actions designed to influence prior elections are still grinding their way through the courts today.

Over the last month, judges in two different courtrooms faced the challenge of managing litigation after the fact, involving prior elections, even as another election looms large.

Justice Juan Merchan, the judge handling the hush money/election interference case in New York, which is awaiting a sentencing hearing while Trump’s legal team appeals Trump’s conviction on 34 felony counts, delayed that sentencing until after the election.

In another courtroom, this one in Washington, D.C., federal judge Tanya Chutkan, presiding over the criminal prosecution of the former president for his alleged hand in efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 election, had a very different response to the fact that the calendar is turning the final stretch of the presidential election of 2024. Although that case will not go to trial, if it does at all, until after the election, Judge Chutkan saw no reason to delay the matter and allowed it to proceed apace.

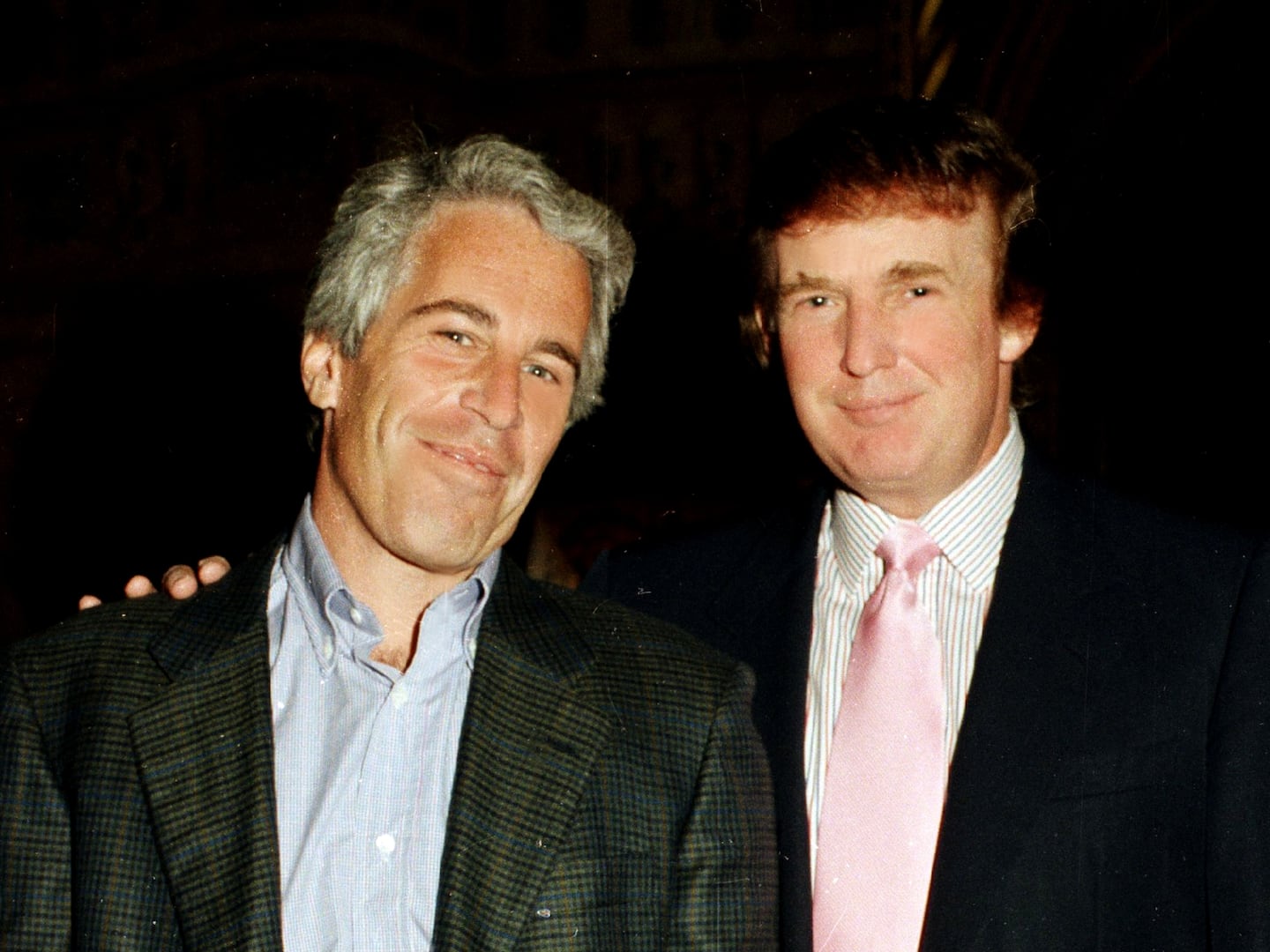

Giuliani and Donald Trump attend a ceremony marking the 23rd anniversary of the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center at the 9/11 Memorial and Museum in the Manhattan borough of New York City, U.S., September 11, 2024.

Mike Segar/ReutersSomeone like Giuliani, now disbarred, will be unable to appear in court as an advocate with respect to the 2024 election should the Trump team lose once again. That does not mean there won’t be other lawyers who might consider stepping into the breach and filing similarly desperate and far-fetched claims. But in at least some states, Republican legislatures and election officials have created systems that will be easier to manipulate to cause post-election mischief.

However, courts should not stand still and wait for cases to emerge and misconduct to take place for them to take any actions to deter such behavior. Indeed, court officials can issue directives to the judges within their systems to make it clear that those judges have the authority to take swift and significant actions should lawyers present baseless claims before them. Courts certainly have specific practice rules that enable them to punish lawyers for misconduct after the fact, but also have the inherent authority to make sure litigants before them—especially lawyers—are not using the courts for nefarious ends. Judges can remind lawyers of that power even before they file a lawsuit.

In addition, judges control their dockets and court calendars. When cases come before them that seek to undermine faith in the results of the election, those judges can schedule hearings on those claims immediately and require that the lawyers making those claims present any evidence they may have. Without real evidence, courts should not hesitate to dismiss those cases and make it clear that lawyers who bring them will face serious professional consequences, as they should.

In these ways, courts can harden themselves as targets, making it more difficult for those who might use them to sow division, prevent the peaceful transfer of power, and generally strive to undermine our democracy.

Of course, we can look at the Supreme Court’s immunity ruling from the end of its last turn for evidence that that court at least, may have become an enabler of insurrection. It is important to note, however, that the federal judiciary, even judges nominated by Donald Trump when he was president, refused to take part in post-election chicanery last time around. When the Supreme Court, which included his three appointments to it at the time, had the chance to get involved in several cases that sought to overturn the results of the 2020 election, it chose not to do so. Will it do the same in 2024 if given the chance?

If lower courts make clear that they will not be the instruments of election interference and establish clear factual records that support their decisions, should the Supreme Court wish to involve itself in such litigation, it will have a hard time finding any basis for doing so.

In the early 19th century, French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville visited the United States and observed that any political question that arose in the new nation tended to end up in its courts. It is highly likely that, should Vice President Harris defeat former President Trump in November, we can expect to see another raft of litigation that seeks to ignore the will of the voters.

But courts are not powerless to merely await such an assault on our institutions and democracy itself. They can and should take steps now to remind judges of the power they have to address such mischief quickly, and with confidence and authority; to dispatch such cases with speed; and perhaps even force some lawyers to think twice before they engage in attempts to undermine our democracy.