The trail of victims from President Putin’s bloody invasion of Ukraine now stretches into another country entirely. Pro-Kremlin rebels in the tiny nation of Moldova have thrown a man into prison for the next three years for the supposed crimes of hanging a Ukrainian flag from his balcony and criticizing the illegal war.

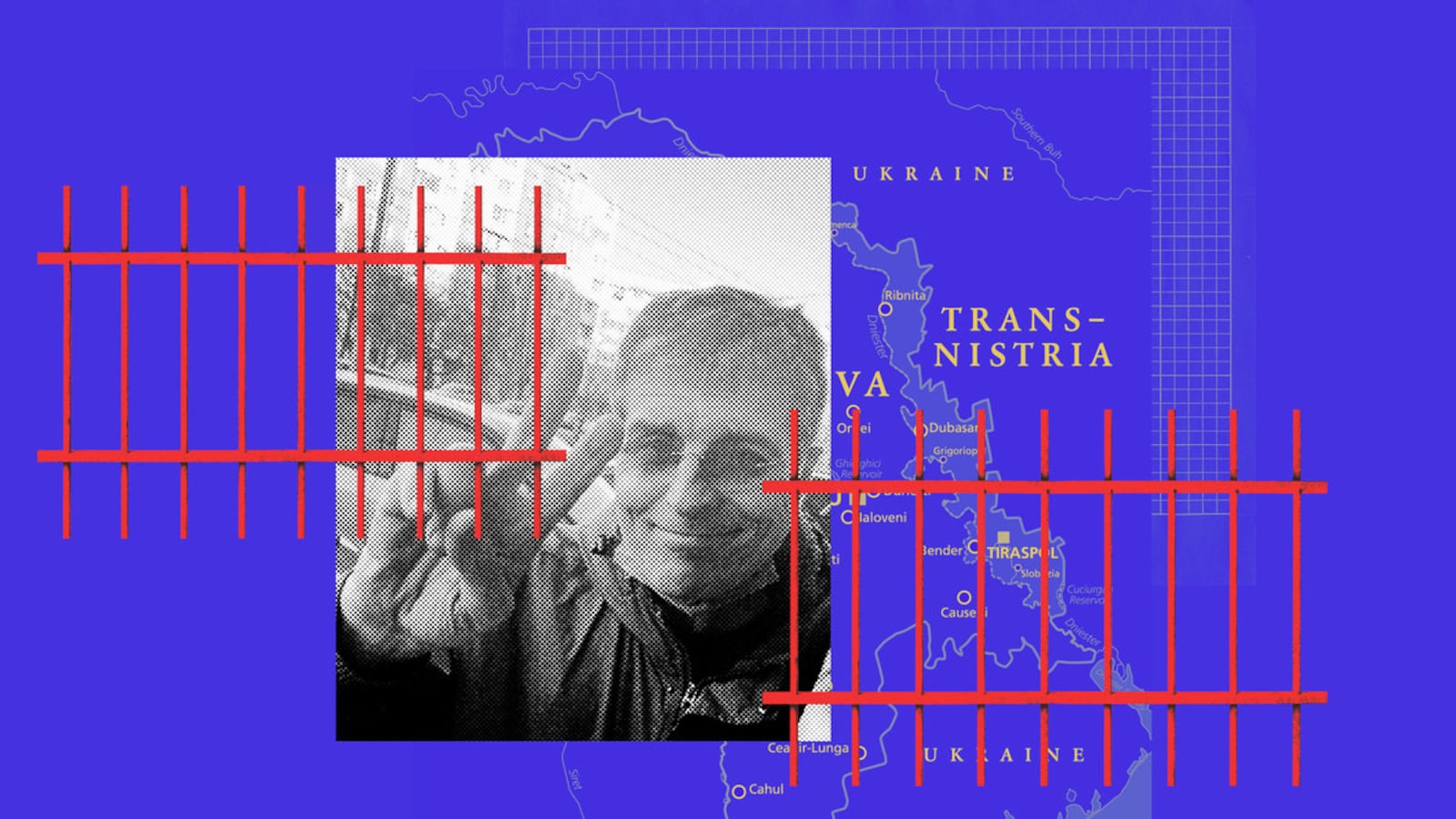

Victor Pleșcanov, 58, was sentenced to his cruel fate last month in the breakaway region of Transnistria, which has been occupied by Russians since 1992. The sliver of land—which is still formally part of Moldova—lies on the border with Ukraine where Russia has been waging war since February.

The pro-Kremlin regime in Transnistria has been cracking down harder on dissenters in recent months in parallel to Putin’s increasingly totalitarian laws in Russia. Pleșcanov has become the face of that struggle.

When he joked that the KGB-emulating security services of the enclave—known as the MGB—would “wet themselves” when they saw the flag, he couldn’t have imagined how brutally he would be proved right.

Pleșcanov had been known for his outspoken criticism of the local kleptocratic regime and the Russian occupation of Transnistria since an invasion of Russian rebels in 1992 when Moldova broke from the Soviet Union. He was placed under close surveillance by the security services of the so-called republic when the war started in Ukraine, finally providing a pretext to place this regime critic behind bars.

Transnistria came briefly to global prominence in March when one of Putin’s henchmen, Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko, unveiled a map of the war in Ukraine that appeared to show Russian forces breaching the border of Moldova, presumably in a bid to take Transnistria into the greater Russia of Putin’s fetid imagination.

The disputed territory previously only garnered rare attention from the world’s media when its soccer team, Sheriff Tiraspol, qualified for Europe’s top club competition, the Champions League.

The owner of Sheriff, Victor Gushan, is the most powerful oligarch in the region and a former KGB officer who is thought to maintain continuing links to the Kremlin.

While Gushan and the other leaders of Transnistria have so far been spared from Western war sanctions and, unlike other Russia-occupied cut-outs, have maintained working relationships with the actual government they operate under, they have also proven their loyalty to Putin by cracking down on dissent, said those with direct knowledge of the situation.

“Pleșcanov must be released unconditionally, no he did not receive any fair trial, [and] no, Transnistria’s so-called courts do not and cannot make justice,” said Alexandru Flenchea, a former Moldovan chief government negotiator and adviser to the U.S. Embassy, who now runs the Initiative 4 Peace association.

“Despite having all appearances of a state, Transnistria is not one,” he told The Daily Beast. “All Transnistrian institutions only serve the interests of the business conglomerate called Sheriff. Sheriff has monopolized the economy, local politics, and has deprived Transnistrian residents from their political and civil rights and freedoms, including the freedom of speech.”

Vlad Lupan, a former Moldovan ambassador to the UN, told The Daily Beast: “The tendencies of the authorities there are to enact vengeful and abusive arrests, not justice.”

Lupan, a New York University lecturer who was a member of Moldova’s negotiating team in the wake of the Russian invasion of 1992, explained that, “Transnistrian separatists are subordinated to Moscow… Their budget depends on the Russian money flows. The region receives Russian gas for extremely low prices, and often avoids paying for it.”

Lupan sees Moscow’s influence deepening as the war continues in Ukraine, right on Transnistria’s doorstep.

“Mr. Pleșcanov’s case is one of the first cases judged after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It also follows the urgent adoption by the Russian affiliated “separatists” in the Transnistrian region of a strategy—doctrine of information security—in March, after the invasion started.”

“Pleșcanov’s conviction is extremely similar to the suppression of war critics in Russia proper.”

One of the reasons Pleșcanov came to be seen as such a threat to the regime this year was his willingness to speak to journalists who have been candid about what is really happening in Transnistria since the war in Ukraine began. Irina Tabaranu, editor of Zona de Securitate, was in contact with him before his arrest in June and continues to report on developments in his case.

“Taking a civic stance is not tolerated by the regime, and maintaining links with journalists who publish critical materials, or featuring in these materials is considered unacceptable,” said Tabaranu. “I am certain that Victor’s position not only on the Ukraine war but also that he does not recognise the authority of the regime made the MGB have such a harsh attitude towards him.”

Pleșcanov’s legal adviser agreed, warning that persecution of opinionated citizens is widespread and getting worse. Pavel Cazacu, a lawyer who represents Pleșcanov and his family pro bono through the PromoLex non-profit organization, told The Daily Beast that “the case is representative of several deep-seated problems in Transnistria, where people who dare to speak out against the regime on any issue, not just the Ukraine invasion, are persecuted.”

Cazacu said that although the sentencing document jailing Pleșcanov in September for three years and two months was never published nor released to his family for potential appeal, the security forces there have told them that Pleșcanov’s social media posts, in addition to his displaying of the Ukrainian flag, were factors in the trial accusing him of incitement to extremism.

He has been under arrest since June and his wife was not allowed to see him until September, said Cazacu. Pleșcanov’s wife declined to be interviewed for this article.

The Tiraspol regime has been aligning its internal legislation with that of Russia over the past several years, and given that the Kremlin has enacted brutal curbs on press and free expression since the invasion of Ukraine, such moves may be made in Transnistria also, the lawyer said.

Representatives of the Tiraspol authorities did not return The Daily Beast’s requests to comment.

Geopolitical experts as well as the Kremlin’s own representatives have indicated, meanwhile, that Russia would annex Transnistria alongside parts of southern Ukraine if it conquers enough of the country to give itself land access to the enclave.

Moldovans have been living with the fear of invasion ever since Feb. 24, when Putin’s tanks rolled over the Ukrainian border and the bombings started. This month as Russia targeted Kyiv with ballistic missiles, three of them fired from a Russian ship violated Moldova’s airspace en route to their targets in Ukraine. Back in July, the Moldovan prime minister, Natalia Gavrilița, told journalists that invasion of her country “is a risk, it’s a hypothetical scenario for now, but if the military actions move further into the southwestern part of Ukraine and toward Odesa, then of course, we are very worried.”

In private discussions, officials are less restrained, with one telling The Daily Beast that “we are living through a very dramatic situation. Our fate is completely tied to Ukraine’s resistance, they are fighting for our independence as much as their own.”

Transnistria has not entered the war because the Russian army present there is not well-equipped enough to battle Ukraine’s forces on its own, but fighters from the territory have been known to join Russia’s army as purported volunteers, and Russia has openly advertised its call-up for soldiers in the region.

A so-called referendum in Transnistria in 2006 showed 97.2 percent of the population would agree to join the Russian Federation instead of remaining part of Moldova. “That referendum is pointed to frequently even today by the de facto rulers,” Cazacu said.

“They do not have an equitable justice system,” Cazacu said, adding that Pleșcanov has several physical and mental health conditions which make detention “very difficult for him to bear.”

“Without constant care packages from his wife he would not be able to survive,” he said, adding that visitation rights in the Transnistrian prison system are not automatic but left at the discretion of the authorities on a case-by-case basis.

Moldovan officials in their interactions with the regime as well as with international partners, have been advocating for the release of all political prisoners and activists imprisoned in Transnistria, including Pleșcanov, a spokesman for Deputy Prime Minister Nicu Popescu told The Daily Beast. “At the UN in Geneva during the three sessions of the Council for Human Rights this year we have talked about the degradation of human rights in the Transnistrian region, the increase in abuses from the separatist authorities relating to the right to assembly and expression, and relating to political opponents of the regime in Tiraspol,” he said.