The U.S. is giving Russia ten accused snoopers in exchange for four. What gives? Reihan Salam says America should have bargained harder.

If nothing else, last week’s arrest of 10 Russian agents has been extraordinarily good news for Svetlana Sutyagina, the mother of Igor Sutyagin, a Russian defense researcher who will soon be freed after 15 years of imprisonment on what appear to be tissue-thin charges of espionage. To its great credit, the Russian government, loathsome though it may be, was willing to cop to the fact that the amateurish spy ring rolled up by the FBI was real and not an invention of Yankee propaganda. Rather than cut loose loyal comrades, nine of whom are Russian nationals and at least one of whom has proven fetching enough to inspire pangs of lusty nationalism and perhaps even a TV movie, the Russians agreed to a good old-fashioned spy swap. Indeed, they agreed to it so quickly that you have to wonder if the U.S. should have bargained a bit harder.

Would the Russians be willing to part with vast quantities of weapons grade plutonium?

The disgraced Russian spies will return home, where one hopes fond memories of backyard hydrangeas will never die. In exchange, the United States has persuaded Russia to release four Russians convicted of spying for the U.S. and Britain, including Sutyagin. Never missing an opportunity to be petty, the Russian authorities insisted that the supposed Western spies first acknowledge their guilt, which must have been particularly galling for Sutyagin, who has long insisted on his innocence. A number of Russian human rights activists have backed Sutyagin’s claim, gutsily accusing the Kremlin of using his arrest to intimidate critical voices. One thorny problem is that Sutyagin, a Russian patriot, reportedly has no desire to leave the country. Though prison was undoubtedly a drag, there is something more than a little tragic about having to live out life as an exile, even if it means trading up to a balmier climate.

Wait a second. So Russian agents in the United States who actively sought to secure valuable confidential information will get to return home. And a handful of Russian dissidents who did little more than run afoul of a thuggish regime will be forced to leave their native country. Is it fair to say that this is much of a swap? The fact that Sutyagin will finally go free is pretty clearly a win for the forces of decency and justice and all that. Yet he’s only going free on the Kremlin’s terms, having “acknowledged”—through gritted teeth—that he was in the wrong. Sutyagin’s case reminds us that Soviet-style paranoia and repression remain present in the new Russia. His 15-year-nightmare is of a piece with the terror and dread experienced by Russia’s small handful of truly independent investigative journalists, and members of its despised Muslim minorities, many of whom live in fear not just of racist thugs but of the police.

Given that the Russians haven’t identified any bumbling American sleeper agents in Russia, at least as far as we know, one wonders what a better deal might have looked like. Would the Russians be willing to part with vast quantities of weapons grade plutonium? Or a best-and-the-brightest assortment of gifted ballet dancers and hockey players and computer programmers and avant-garde novelists? When we consider the extraordinary success of the hundreds of thousands of Russian emigres who’ve settled in the U.S. since the legendary Senator Scoop Jackson came to the rescue of so-called Soviet refuseniks, you could say that we’ve already gotten the better end of the deal. But is it wrong to expect a little bit more? If nothing else, a bigger concession would convey due respect for the excellence of the FBI’s counterintelligence team.

Though Russia in the age of Vladimir Putin and his flunky Dmitry Medvedev is hardly a liberal paradise, the country has come a long way since the days of the Gulag Archipelago, the vast network of forced labor camps in which millions of political prisoners and common criminals were worked to death, leaving countless families broken and bereft. After decades of pressing and cajoling Russia to press ahead with political and institutional reform, it seems that there’s not much more the United States can do to compel Russia to become a freer, more open society. Russia hawks are furious over what they see as President Obama’s efforts to accommodate Moscow’s expansionist designs. But with a very full plate of crises both foreign and domestic, is it fair to expect anything else?

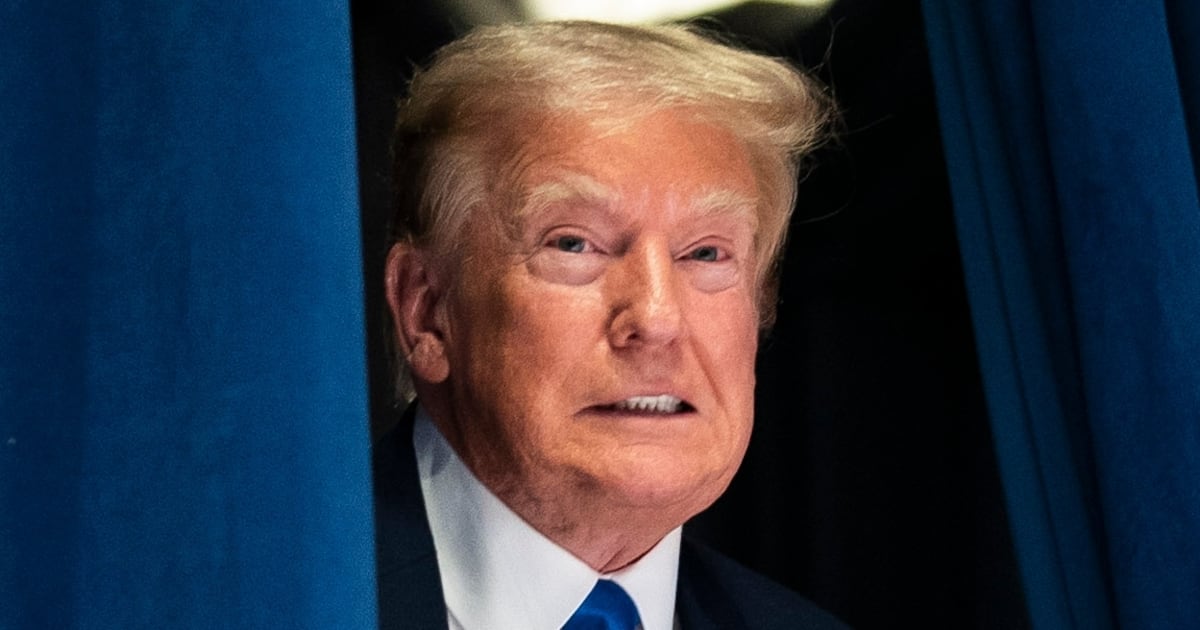

Reihan Salam is a policy advisor at e21 and a fellow at the New America Foundation.