Last week, 10 months after Russia invaded his country, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky made an uncertain trip to Washington, D.C., to ask the U.S. for additional aid to finally end the conflict—which continues to stoke fears over environmental catastrophe in the wake of Russian attacks on Ukraine’s nuclear power plants, as well as Russian threats over the use of nuclear weapons. Among other measures, Zelensky asked the U.S. to “strengthen tariffs” against Russia, and render the war financially unsustainable. This would particularly affect areas of science and technology research where Russia has traditionally excelled, including physics, space exploration and climate science.

But despite widespread Western support for Ukraine, it has proven difficult to disentangle U.S. scientific and technical collaborations with Russia. In many cases, resistance is coming from American scientists themselves, who argue that theirs and their colleagues’ work is too important and urgent to disrupt, particularly surrounding climate change research as global warming accelerates.

Days before Zelensky’s speech, an editorial published in Nature magazine urged that science not be treated like a “diplomatic pawn,” and the war “must not become a barrier to countries working together” on to tackle pressing scientific issues such as climate change. Physicist Michael Riordan from the University of California, Santa Cruz, espoused a similar sentiment in The New York Times back in late August, proclaiming, “I’m a physicist who doesn’t want Russia to leave the world of science.”

Others see things differently. “During the Cold War, Russia was a science powerhouse,” Marcia McNutt, president of the National Academies of Sciences in the U.S., told The Daily Beast. “But since the fall of the Soviet Union Russian science has not been as strong. When you look at the big issues of the day, like gene editing, I just don’t see Russia as being in the forefront.”

At the same time as Russia’s scientific contributions have weakened, Ukraine has risen up as a leader in science in Eastern Europe and former Soviet states, particularly in areas of agriculture research and nuclear power.

When Russia first invaded Ukraine on Feb. 24, Europe responded swiftly to cut ties with Russia, and that included science and tech endeavors. Germany announced that it was ending all scientific collaborations with Russia the very next day, and other European Union member nations soon followed with similar comprehensive bans. CERN, a multinational particle physics lab in Switzerland and home to the famed Large Hadron Collider, suspended Russian membership in early March, as did the European Space Agency and the Max Planck Institute. ESA’s actions were particularly consequential, as its joint Mars rover mission with Russia is now in complete limbo for the time being.

In contrast, the U.S. scientific community’s response has proceeded somewhat unevenly. The Biden administration remained silent on the status of U.S.-Russia collaborations until June. That month, they announced that the U.S. would start to “wind down,” all current federally funded research projects partnering with Russia, and prohibited new projects.

“Considering the war crimes and other atrocities Russia has perpetrated it was very important for us to make an unequivocal statement of support for Ukraine,” a government official who was involved in the discussions but has since moved to another job in the administration, told The Daily Beast on the condition of anonymity.

“But at the same time,” the official said, “we acknowledge there is a strategic need to engage with Russia” in order to avert the kind of global destruction that loomed over the Cold War.

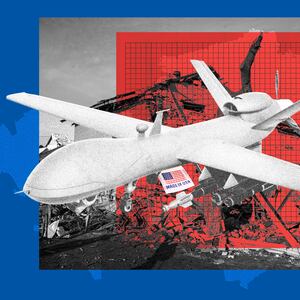

Since the beginning of the war Russia has targeted Ukraine’s scientific infrastructure. Ukraine’s Institute of Physics and Technology in Kharkiv has been heavily damaged by Russian bombs. At Chernobyl and other nuclear power plants and research facilities, Russian troops have looted or destroyed millions of dollars worth of high-tech equipment and computers. At least 20 Ukrainian universities have been completely destroyed.

To keep the war from sliding into a full destruction of Ukraine’s higher education institutions and a potential nuclear disaster, the Biden administration has refrained from cutting scientific ties to Russia completely—a policy formulated by the Office of Science and Technology Policy, which advises the president on all matters related to science and technology. The four month gap between the invasion and policy announcement was likely “a reflection of the nature of U.S. scientific enterprise” and the “decentralized research community,” in the U.S., the government official said.

Culturally, the science community has always been more immune from international schisms that characterize many other fields of work. For many scientists, there’s resistance to having to cut off access and partnerships with groups because of a war. One of CERN’s mottos, for example, is “science for peace.”

“There’s ample evidence that many Russian scientists want no part of Putin’s war. We want to ensure that those individuals have a clear pathway to engage with us or leave Russia if they so choose,” the official said.

“Within the scientific community there are mixed feelings and a variety of views about what is the appropriate response,” Raymond Jeanloz, a professor of earth and planetary science at the University of California, Berkeley, told The Daily Beast. “Many of the people that we talk with know each other, or work with each other in one form or another for years or decades. They are friends.” Jeanloz is also the chair of the Committee on International Security and Arms Control at the National Academy of Sciences, a private, non-profit, non-governmental organization funded primarily by federal grants. Its research is used to inform the OSTP.

A prevalent opinion is that it is not fair to judge individual scientists based on the actions of their government. Indeed several thousand Russian scientists signed a letter denouncing the invasion soon after it happened.

But Russian science is inextricably tied to the Russian government. The majority of the country’s scientists are at least partially funded by the Russian government.

And in September, the election for leadership of the Russian Academy of Sciences showed evidence of state meddling: The incumbent president withdrew his candidacy the day before the election, in what he called a “forced decision.” Gennady Krasnikov, the head of Mikron, Russia’s largest chipmaker, was elected instead.

The Biden administration imposed sanctions on Mikron back in April, in a broad panel of sanctions against the aerospace, marine and electronics sectors in Russia. Another round of sanctions in August targeted the Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, or Skoltech, founded in 2011 as a partnership with the Massachusetts Institutes of Technology to build out a Russian version of Silicon Valley. MIT announced it was shutting down the $3 billion partnership back in February—the day after the invasion.

On Earth—and Above It

Climate change research is an area where Russia’s contributions will be difficult, if not impossible to replace. The vast majority of the world’s permafrost, which scientists track to measure the rate of global warming, is in Russia. Russia currently chairs the Arctic Council, a consortium of eight nations that promotes cooperation on climate change research. At dozens of research stations in Russia, international teams of scientists collect permafrost samples by drilling boreholes in the earth.

Soon after the invasion started, the seven other members of the Arctic Council, which includes the U.S., halted their participation in the council. They have since resumed research without Russia. Some of the research has been transferred to Canada and Greenland, which are home to permafrost reserves of their own. But that still paints an incomplete picture, and may not accurately reflect what is happening to permafrost in Russia—a big problem when one degree of change can throw off the entire model.

“It’s the difference between ice and water,” said Brendan Kelly, a professor of marine biology at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks and a member of the International Arctic Research Center. “Not being able to involve [Russia] is a significant detriment. It will be a big loss to us as we are trying to understand on a pan-Arctic scale what is happening in the Arctic.”

Russians have been massive contributors to climate knowledge, Kelly said. But at the same time, they “haven't been the best team player in terms of data sharing.” That has been an issue going back decades, according to Kelly.

In other areas of science, a clean breakup is near-impossible. Perhaps the quintessential example is the International Space Station—a collaboration between the U.S., Russia, Japan, Canada and the European Space Agency, the first piece of which launched in 1998. The ISS literally cannot operate without both Russia and the U.S., which supply propulsion and power, respectively. Scientists on the station conduct experiments primarily to see how things function in microgravity, to prepare for long-term space flight. For decades, it has been lauded as an example of international cooperation, between parties that don’t always share the same goals in other areas of geopolitics. And the lives of the astronauts on board the ISS has always required both countries’ space programs to insulate themselves from deteriorating relations in other areas.

But that insulation has eroded as the invasion has progressed. In July, Russian cosmonauts on the ISS staged a picture in which they held up Russian and anti-Ukrainian flags in an episode of propaganda that drew “strong rebuke,” from NASA. That month Russia announced that it planned to withdraw from the ISS in order to focus on building its own structure, but later walked that back and confirmed its participation until 2028 (a few years before the station’s formal shutdown in 2031.)

And in September, NASA and Roscosmos, the Russian Space Agency, collaborated to send astronaut Frank Rubio and two cosmonauts to ISS on the Soyuz MS-22 spacecraft, launched from Kazakhstan.

Good Substitutions

Ultimately, there is no easy action that can satisfy all parties involved. “Obviously the war is obscene,” Kelly added. “It’s a devastating humanitarian crisis. But we also have a crisis with the climate, and not being able to advance our understanding of where the climate is headed is going to cost human lives and human wellbeing in the long run. I don’t know how to divide the baby here. It’s not an easy call.”

As of now, the total destruction in Ukraine is vast. Nearly 7,000 Ukrainian civilians have died since the start of the war, according to the U.N. And Ukraine’s scientific infrastructure and nuclear power plants continue to be under threat from Russian forces.

While many American scientists are hoping the conflict ends soon and they can return to somewhat normalized relations with their Russian counterparts, others consider the war to be an inflection point that could—and should—encourage the West to rethink its scientific partnerships across the board.

Some even think Ukraine itself could help fill the void left behind by Russia. To that end, the NAS has set up a sort of exchange program setting up displaced Ukrainian scientists with positions in Western universities and research institutions.

“Ukraine needs its researchers in order to rebuild. Russia has experienced significantly less damage from this war,” McNutt said. “We’re not talking about needing to rebuild Russia.”