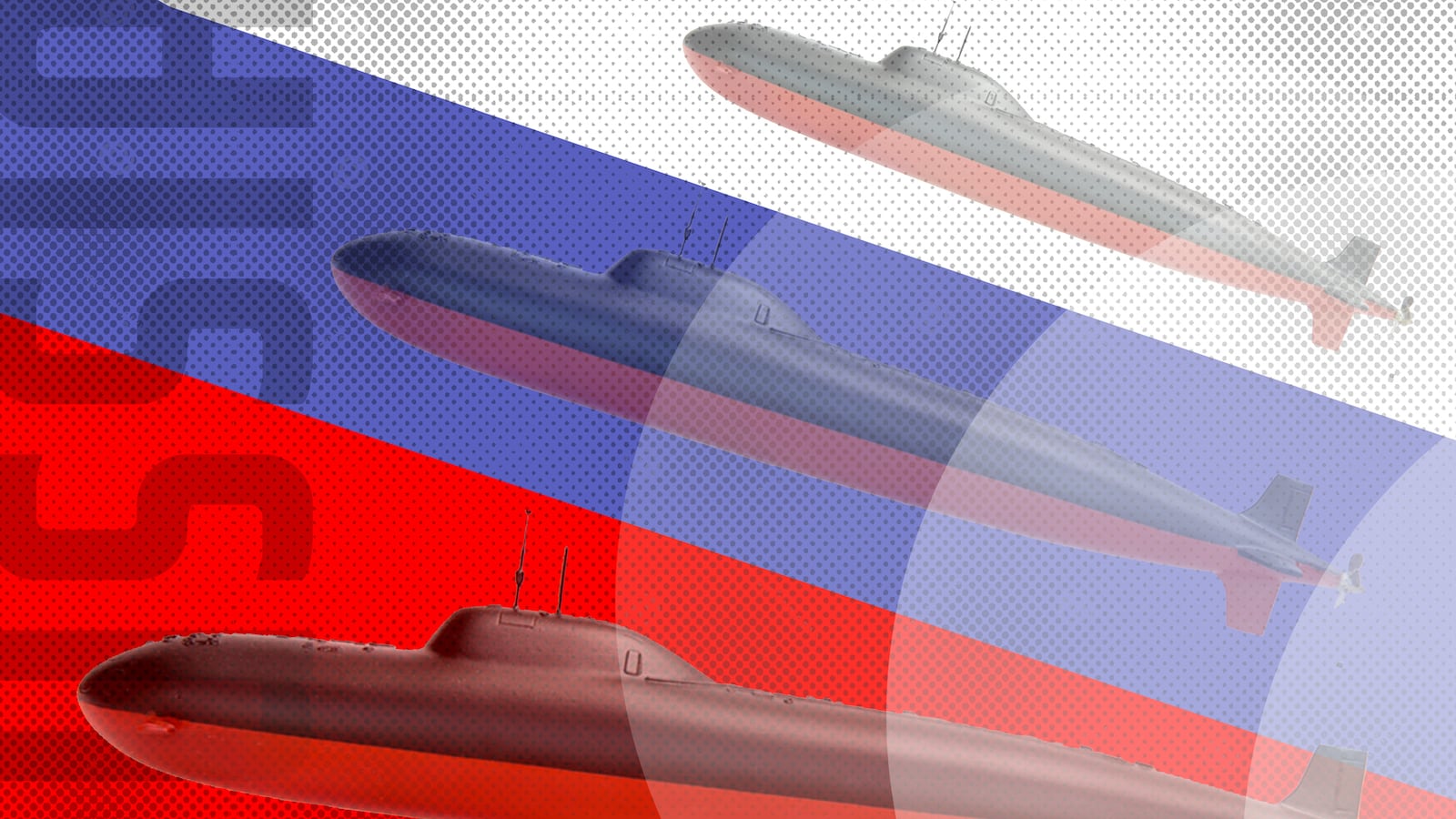

On August 11 at the port of Severodvinsk in northern Russia, a huge and imposing black shape emerged from a dry dock, observed by ranks of uniformed dignitaries. The Russian navy’s latest submarine is 574 feet long, displaces no fewer than 18,000 tons of water and packs two nuclear reactors.

Named Moscow, she’s actually a refurbished, 1980s-vintage ballistic-missile sub that once prowled underneath the Arctic ice, cradling nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles, awaiting Armageddon.

Today, as best as any outside observer can tell, the Moscow has a new mission. She appears to be part science vessel, part spy ship, part commando transport, and part “mothership” for mini-subs and drones.

But no one outside of the Kremlin and the Moscow’s future crew knows for sure.

“There’s a lot of questions here,” says Eric Wertheim, a leading naval analyst in the United States and author of Combat Fleets of the World, the definitive naval reference guide.

One thing is certain: Whatever her purpose, the Moscow is the most recent sign of Russia’s desperate effort to rebuild its dilapidated navy and, a quarter-century after the Cold War ended, once again challenge the U.S. Navy on—and beneath—the world’s oceans.

Special mission boat

Moscow began life as a Delta IV-class ballistic missile submarine, crewed by 135 sailors and armed with 16 intercontinental-range ballistic missiles, each with four independent warheads that can split off from the rocket as it plummets toward Earth, maximizing the city-destroying power of each missile.

In 1999, the Kremlin ordered the Moscow into dry dock in Severodvinsk for rework initially costing 443 million rubles, or around $7 million. The plan—to remove the submarine’s missile tubes and replace them with new equipment for covert missions, transforming the Moscow into what navies call a “special mission” vessel.

Where ballistic missile subs haul atomic weapons and so-called attack submarines armed with non-nuclear missiles and torpedoes silently stalk surface ships and other subs, special-mission boats handle, well, everything else that an undersea warship can do: testing new technology; quietly transporting naval commandos on deadly secret missions; supporting deep-diving mini-submarines and free-swimming underwater robots; and, perhaps most provocatively, gathering intelligence—and preventing the enemy’s submarines from collecting intel of their own.

The United States is the world’s leader in submarine technology and possesses the most technologically advanced special-mission subs, including four converted ballistic-missile submarines plus the mysterious USS Jimmy Carter, a one-of-a-kind spin-off of the Seawolf class of attack boats.

Entering service in 2004, the $3 billion Jimmy Carter is one of the Navy’s most secretive warships. The sailing branch does not comment on the vessel’s features and deployments. But Owen Cote, a submarine expert at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said the ship probably has a “moon well,” a kind of floodable chamber that allows divers and undersea drones to exit and reenter the sub while the ship is submerged.

It’s unclear exactly what the Jimmy Carter does during her months-long deployments, but it’s possible she heads to the ocean floor so her divers and robots can place wiretaps on undersea cables, allowing U.S. intelligence agencies to listen in on intercontinental communications including Internet traffic. During the Cold War, U.S. special mission subs frequently penetrated Soviet defenses to bug Moscow’s communications cables.

These days there are better ways to tap into the fiber-optic cables that carry global communications. “I don’t think you need to use Jimmy Carter to do that,” Cote said. “It would be a waste of that asset.”

But one Russian ex-official insists that NATO, the U.S.-led European military alliance, still taps Moscow’s cables. “I note that every year a certain number of such devices is removed from our links,” retired admiral Viktor Kravchenko, former chief of the general staff of the Russian navy, told one Russian news site.

Indeed, Kravchenko claimed that the Moscow’s main mission will be to transport a nuclear-powered mini-sub that can descend to great depths to remove the wiretaps. The Moscow’s mini-sub could also place its own wiretaps, according to Valentin Selivanov, another retired Russian admiral and former submarine commander.

Like Cote, Norman Polmar—a naval expert who has advised the U.S. government on submarine strategy—dismissed all this talk of wiretaps. “There are very few Russian undersea cables that are tappable,” Polmar said. Besides, he added, “more stuff moves through the air.”

Cash is king

Still, Polmar cautioned against underestimating the Moscow. Whatever the submarine is for, it could be something American observers can’t even imagine. “Is there something surprisng in that submarine?” Polmar asked. “It’s possible.”

Polmar said he has visited, multiple times, all of the engineering bureaus that design Russia’s subs. “These guys are far more innovative than we ever were.”

But before the Moscow can take on secret missions, the Kremlin has to wrap up the submarine’s rework—a process that, so far, has taken a staggering 16 years… and might never get finished.

Russia’s naval shipbuilding industry still possesses impressive expertise, but has suffered from inconsistent and inadequate government funding ever since the Cold War ended. From a peak of hundreds of undersea vessels during the Soviet era, today the Russian navy can put to sea just a couple dozen submarines, roughly half as many as the better-funded U.S. Navy can manage.

“The trouble with all these naval issues is that, unlike some programs that are small, ships are systems of systems and require stable funding over a long period of time,” Wertheim said. And stability is the one thing the Russian economy—and by extension the country’s military budgets—definitely lack.

The Moscow left dry dock on August 12 but could still be years away from being combat-ready. A photo of her relaunch shows construction scaffolding on top of her hull. But Wertheim said he expects the Kremlin to push hard to complete the sub, despite the challenges. “They don’t want to lose that intelligence-collection capability.”