This article was reported in collaboration with Dossier Center and Project.

Warlord Khalifa Haftar began an assault on Tripoli, the capital of Libya, last April. He had seized control of vast swaths of the country with the apparent backing of Russia, the UAE, France, and Saudi Arabia, so the offensive by the self-declared field marshal of the “Libyan National Army” raised fears that the city might fall. But five months later, the warlord’s forces are still fighting in the area and appear no closer to capturing Tripoli.

One group of people who will not be surprised by this turn of events is a team of shadowy Russian operatives working for an organization heavily implicated in the Kremlin’s adventures from Ukraine to the Central African Republic, Venezuela, Syria, Sudan—and, not least, Vladimir Putin’s covert efforts to influence the U.S. elections of 2016.

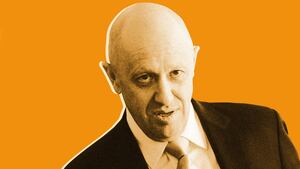

There have been numerous reports over the last two years of Russian support for Haftar, including claims made by British government officials in March this year about 300 mercenary fighters belonging to the so-called Wagner Group, funded by Yevgeny Prigozhin, an ex-con turned caterer with the benefit of huge contracts from Putin. Prigozhin has become the center of a vast network of companies, including media, “troll factories,” oil and mining operations, and private military contractors such as Wagner waging plausibly deniable interventions on behalf of Moscow in trouble spots all over the world.

Working in collaboration with the Dossier Centre, a London-based investigative team funded by former Russian oligarch and political prisoner Mikhail Khodorkovsky, and The Project, an independent Russian news portal, The Daily Beast has examined a tranche of internal communications from deep inside Prigozhin’s Libya operation, always referred to simply as “the Company.” These files, originally obtained by the Dossier Centre, offer documentary proof that Russia’s military role in Libya is far more extensive than has thus far been reported.

They show that, quite apart from running guns for hire and arranging Facebook propaganda campaigns, Prigozhin’s operatives lately got into the business of “government-in-a-box” political consultancy. The Russians appear willing not only to arm but also do PR work for a variety of dubious—and rival—factions in Libya, yet they harbor no illusions as to the popularity or leadership qualities of any of these proxies.

They openly advocate rigging elections, for instance, to help Haftar in the likely event he runs for the Libyan presidency. But the Company certainly takes a dim view of what he’s achieved thus far and of his honesty as a Russian client. It accuses the warlord of using his publicized relationship with Russia as a bargaining chip with other actors to raise his stature—all the while failing to cooperate with or even hindering Company personnel.

Haftar, Prigozhin’s men allege, consolidates territory not by winning battles but by bribing tribal leaders and officials for the right to plant the LNA flag, using a total of around $150 million provided by the United Arab Emirates.

One memo, written on April 10 this year, claims that Haftar even spread disinformation about the presence of 300 mercenaries from the Wagner Group, going as far as having Libyan National Army troops stick paper copies of Russian license plates to their vehicles in order to give the impression of Russian support. (Company employees were dispatched to peel off these fakes.)

Nor has the Company been the model of transparency and loyalty in its dealings with Haftar. Remarkably, it entered into an agreement with the leader of Sudan’s notorious Janjaweed militia and Rapid Security Forces, which were responsible for atrocities during the Darfur genocide and the massacre of protesters in Khartoum this June, to attack forces allied to Haftar during his assault in Tripoli. The goal here apparently was to strike a cynical balance of power in Libya—“equilibrium,” in the Company’s phrase—to the benefit of Moscow.

Another set of documents outline a strategic alternative to boosting the unimpressive field marshal’s political fortunes—a campaign to help his opponent Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, son of the late dictator Muammar Gaddafi and an international fugitive from charges of crimes against humanity.

Here again the Company is quietly scathing in its depiction of the man it would make president, judging Gaddafi’s competence and psychological disposition unfit for the purpose. On April 3, they presented Gaddafi with a McKinsey-style PowerPoint presentation showing how he might make Libya great again. A post mortem of that encounter suggests this would be no easy undertaking. Gaddafi “has a flawed conception of his own significance,” the post-meeting summary states, arguing that, to work with him, the Company would have to babysit him: “We can’t meet with him once a week, we need a constant presence.”

In an effort to boost Gaddafi’s visibility in Libya, the Company set about rehabilitating an old propaganda channel of his late father, Jamahiriya TV, which was taken off-air during the 2011 uprising. The outlet resumed broadcasting in 2012 from a location in Cairo, but suffered frequent breakdowns and interruptions. Prigozhin’s men paid off its debts to both staff and satellite providers.

The Company also went about building up a social-media apparatus to promote both Haftar and Gaddafi using methods reminiscent of what Prigozhin’s Internet Research Agency got up to during the 2016 U.S. election. It created at least 12 different Facebook groups simultaneously working to promote both Libyans. According to one March briefing, these pages were viewed by over two million users each week, compared with the “usual audience for Libyan Facebook groups” of at least 250,000.

Perhaps the most significant disclosure in these files is the naming of a current Russian military officer operating in Libya. An April 6 briefing report states that the Libyan National Army (LNA) had suffered heavy losses as a result of precision artillery deployed by forces loyal to the U.N.-recognized Government of National Accord using advanced munitions.

“Representatives of the LNA,” the document states, “appealed to the commander of the Russian group, Lieutenant General A.V. Khalzakov, with a request to deploy a Russian UAV to identify the location of these guns and enable the LNA to capture or destroy them, which was denied.”

This apparently refers to Lt. Gen. Andrei Vladimirovich Kholzakov, a deputy commander of Russia’s Airborne Assault Forces, although the document doesn’t state where exactly in Libya he is deployed or what his specific functions are.

British intelligence officials told The Sun in October last year that Russia had established two bases in Benghazi and Tobruk, with “dozens” of Russian GRU officers and Spetsnaz special forces troops performing “training and liaison roles.” Alexei Kondratyev, deputy chair of the Russian Senate Defense Committee, denied this, telling state media that Russia had no military servicemen in Libya and was not planning to send any, claiming that the report was an attempt to “discredit Russia in its fight against terrorism.”

Prigozhin’s long arm in North Africa has already rung alarm bells in Washington and Europe.

On May 17 Maksim Shugalei and Samer Hassan Seifan, two Russian nationals, were arrested by the Government of National Accord and accused of attempting to interfere in domestic politics. A letter from the Libyan Prosecutor General’s office seen by Bloomberg claimed that the men were carrying laptops and memory sticks that contained data related to Prigozhin’s interests.

An organization in St. Petersburg, the Fund for the Defense of National Values, acknowledged that both men were “sociologists” who had been working for them in Libya in order to “observe the situation,” denying any political interference. The Fund is headed by Aleksandr Malkevich, who received press attention after he was ejected from rented offices in Washington, D.C. last June after attempting to launch a news website called USA Really, a subsidiary of RIA FAN, the news agency run out of the same former premises of the Internet Research Agency, also based in St. Petersburg.

Malkevich confirmed to Foreign Policy that his employees had indeed met with Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, but claimed allegations of interference were a U.S. “deep state” project.

Another employee of the Fund, Aleksandr Prokofyev, was named in the Libyan prosecutor’s letter. Prokofyev had allegedly been in Libya with Shugalei and Seifan, but had managed to evade arrest. He had in fact returned to Russia on May 14, three days before the arrests were made, as he was on annual leave.

Prokofyev told the New York-based Russian-language RTVi news channel that he had been in Libya and had met with Gaddafi, though he again denied political interference, claiming that Gaddafi was not engaged in any political activities—something disproven by these Company documents.

As it happens, Prokofyev’s name appears in the metadata of that April 3 summary of the Company’s meeting with Gaddafi, suggesting that Prokofyev himself or someone with access to his computer drafted the document.

Three other Company files The Daily Beast examined were authored or modified by Pyotr Bychkov, a member of the board of trustees of the Fund for the Defense of National Values and, according to RTVi, the head of the Prigozhin “back office” responsible for coordinating African operations.

The battle for Tripoli, meanwhile, persists with no sign of a breakthrough by any side, despite the Libyan National Army’s insistence that the city will be taken “at any moment.” And, despite its serious misgivings about Haftar and attempts to countermand his lackluster campaign, Russia continues to back him. According to Maghreb Confidential, a private French intelligence portal, the field marshal was in Moscow just weeks ago, from Aug. 20 to 24, possibly to endear himself to those who clearly neither admire nor trust him.