On Nov. 17, 1948, police were called to the home of society matron Idella Thompson on tony Deer Creek Drive in the heart of the Mississippi Delta. The house was quiet, but as they made their way further inside, they discovered a grim scene.

Idella was lying dead in her bathroom, which was “as bloody as could be,” Leland police chief Frank P. Aldridge said. Next to her lay a pair of pruning shears, the kind home gardeners everywhere use to cut roses and manicure their flower beds. It was the obvious weapon responsible for over 150 small, bloody cuts that covered Idella’s body.

What happened next shook the community, and has echoed through the generations. When Beverly Lowry began to report on the murder that colored her childhood in Greenville, Mississippi, for her latest book Deer Creek Drive: A Reckoning of Memory and Murder in the Mississippi Delta, she found a town still hesitant to speak of what happened even though over 70 years had passed. But perhaps even more surprising than the murder is what the town did about it.

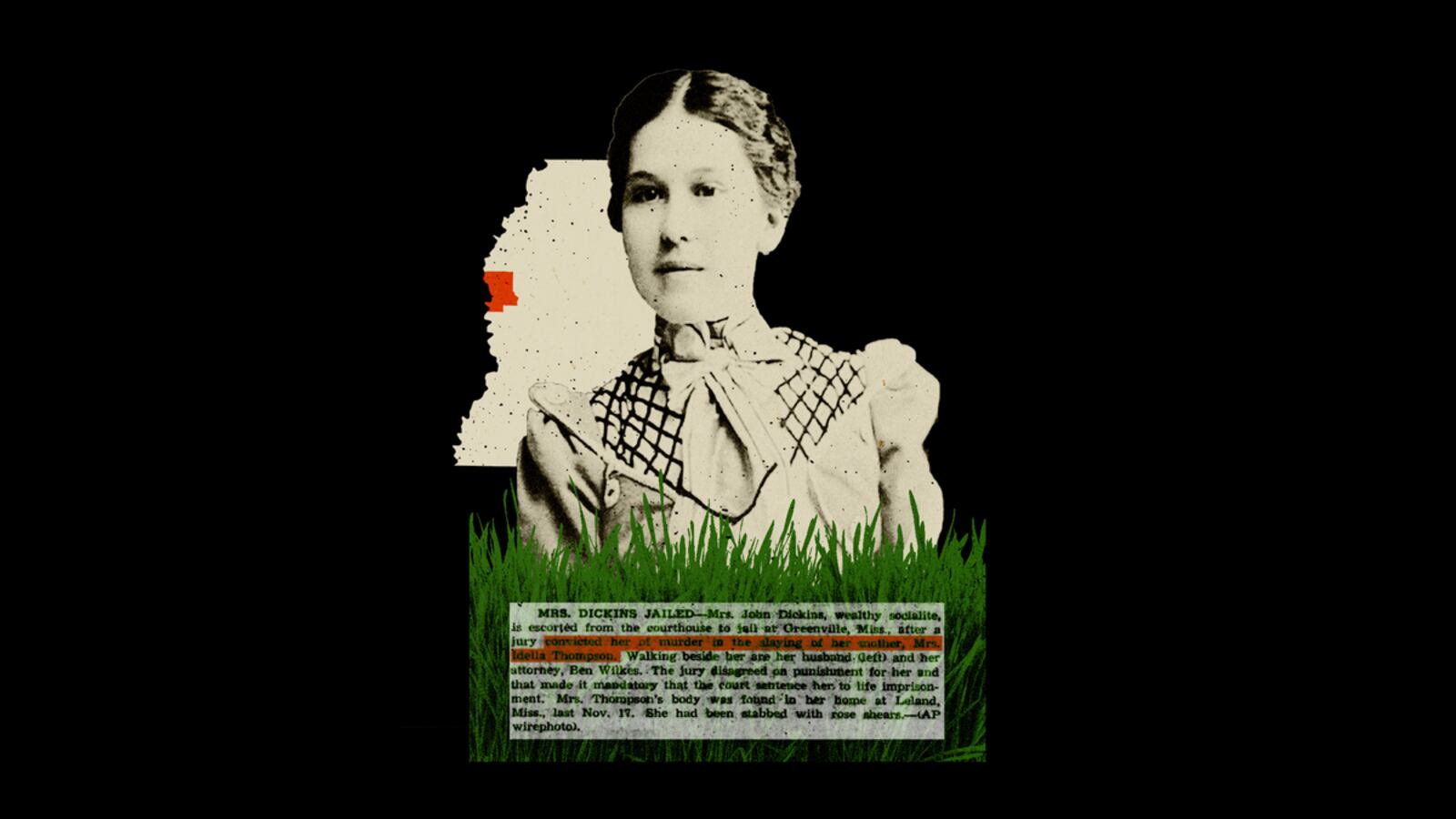

Earlier this week, a grand jury in Mississippi decided not to indict the white woman responsible for the accusation that led to the lynching of Emmett Till. But seven years before that horrifying murder took place and only an hour away, the very white and very segregated powers that be in Leland, Mississippi, investigated the death of a prominent planter family matriarch and came to a single conclusion: Idella’s daughter Ruth Thompson Dickins, the only eyewitness, may have pointed her finger at a Black man, but that accusation was clearly false. Instead, they tried and convicted Ruth, a mother, socialite, and respected member of society, for killing her own mother.

“It was both horrifying and exciting”

This is the “story that had been waiting for me to write all these years,” Lowery, 84, says. She was 10 years old when the murder happened and she remembers following every beat of the investigation and trial in the local newspaper.

“We all knew that it was the biggest thing that had ever happened. And it was both horrifying and exciting in the way that those things can be, I think particularly to girls of that age,” Lowry tells The Daily Beast. “You're wondering, what is out there, what sex is, and this comes along, and it's terrifying.”

From the moment police arrived on the scene, the investigation was a mess, as can happen in a small town where everyone has a personal relationship with nearly everyone else and many of the players involved are related. As word quickly spread about what had happened—thanks in no small part to the loud sirens and nosy switchboard operator—the white members of Leland began to converge on the scene, which had not been properly secured.

The door was left wide open and too many people were allowed to walk around inside, tracking blood around the house. The investigators took Ruth’s word for what had happened and saw nothing wrong with allowing the messy crime scene to be cleaned up soon after. They also allowed Ruth to return to her home just a few doors down without thoroughly questioning her. It was only later that they realized it might have been useful to preserve her bloody clothes, now washed clean of any evidence.

What Ruth told them before she took to her bed was that a Black man she didn’t recognize had come into the house and attacked her mother. Idella was known to be “right difficult” and very protective of the pecans that grew in her backyard. Ruth said maybe what happened was Idella started going off on the man for picking her pecans, something that happened regularly. Maybe Idella grabbed the pruning shears Ruth had left behind earlier that day, and the man in an act of self-defense-turned-rage grabbed the “snips” from her and began to attack.

At her words, a posse of white men on horseback rode into the Black part of town to try to find a man fitting Ruth’s description. Before the night was over, a few suspects had been rounded up for questioning, but they were all released the next day. It was pretty clear even then that no one matching Ruth’s description was going to be found. One woman remembers her father coming home from the search party and immediately saying, “There’s no Negro. It’s somebody in the family.”

Given the time period and how things were so often done in the Jim Crow South, “It is a remarkable part of this story that they didn't come up with somebody, get rid of him, and the story would have been over, except for the family of the person who didn't do it,” Lowry says.

Instead, less than two months later a grand jury indicted Ruth for the murder. On Jan. 8, 1949, Ruth was taken into custody.

In small towns, in towns who’s most prominent members “came there at the end of the 19th century, the families built huge houses, and they're [still] there now,” as Lowry says, it’s hard to completely bury family secrets. While polite society may overlook them for a while, the rumors never truly die.

The Thompson family was among the top echelon of Leland society, but their past was just as colorful, their quirks just as plentiful, as any family. The whispers that swirled around them got louder after Ruth’s arrest.

This was not the first mysterious death in the family. Idella’s husband had died nearly a decade earlier in a suicide that had been covered up to avoid the shame. But even after the suicide came out, questions lingered. Could a man really shoot himself twice in the head? Then, there were rumors of the strange death of another husband in the family, possibly the first husband of Ruth’s sister? Lowry was never able to confirm that such a man existed, much less died, but that didn’t keep the town from talking.

Ruth’s oldest brother, Jimmie, was “disturbed—there was something about him” as Lowry characterizes it. And then there was Ruth herself, a woman who refused to conform to convention. Sure, she got married at an early age to a husband who was devoted to her, had two children, and was by all accounts—especially those of the defense—the perfect daughter.

But in other ways she lived well outside the norm. She wanted to be more than a wife and mother, which is why she took over running the family land with one of her brothers after her father’s death. When the business began to flounder, she took loans from several banks and friends around town, always requesting that her husband not be informed. And then, there was her appearance (when is it not with women who go against convention). Much talk around the trial surrounded her “mannish bob” hairstyle, and the fact that she dressed more practically than femininely.

If the Thompson family thought the justice system would go easy on Ruth because of her prominence and her most sacred of southern identities—a white mother—they were in for a big surprise. From the first day of jury selection, the trial was treated like a circus. Townspeople lined up early to get good seats, vendors sold refreshments inside and out of the courtroom, and the crowd was so enamored with the prosecutor that they once clapped for him when he entered the courtroom. The overwhelming sentiment was: Ruth was guilty.

“I know people are saying that. That is terribly unfair and false. I believe you could search the country over and never find a person who could honestly say he saw me in a fit of temper,” Ruth told The Commercial Appeal ahead of her trial. “How could anyone who loved her mother as I did want to kill her?”

Despite her emphatic denial and her husband’s dogged belief that she was innocent, Ruth was found guilty of first degree murder. It was a harsh sentence—if she had killed her mother in a spontaneous fit of rage, probably over money though the motive is still unclear—the more appropriate charge would have been manslaughter. Instead, she received the lightest punishment possible for the charge: life in prison rather than death by the electric chair.

Ruth would go on to serve only six years and through her husband’s never-ending campaigning and political maneuvering, she would eventually not just get out of prison but also receive a pardon. While many—though not all—in Leland would come to agree that she had done her time and deserved to be home with her family, not many outside of her own family really questioned whether or not she was guilty. Or if they did, the finger didn’t move too far from the family tree.

If Ruth didn’t do it, then the runner up for most likely murderer is Jimmie. This theory goes that Jimmie was the one who killed his mother in a sudden fit of violence, and his sister Ruth, who had always taken care of him, covered it up, taking the suspicion under the assumption that a midcentury Mississippi court would go easy on a prominent white woman. While there is some compelling evidence that this could have happened, Lowry presents a persuasive argument that the more likely suspect was the one who did the time.

Deer Creek Drive is a rich and compelling read as Lowry deftly weaves the unraveling of her own family secrets with those of the Thompson-Dickens family in the wake of Idella’s murder, all set against the eve of the Civil Rights Era in the Mississippi Delta.

Lowry writes, “Small towns love to tell stories about a local boogeyman. In Leland, the boogeyman was, for many years, a woman.”

But, for her own part, she couldn’t help coming to admire Ruth.

“I just came to think of her as a special character. Really smart. Way too smart,” Lowry says. “I’ve known a number of women like that who come from the era before mine. And I think when you look at Ruth lying—well, not lying but saying, ‘Don’t tell John’ [about her debts]—she wants to be in charge. She wants to have her own life.”