When Allen King allowed the Farrell-Cooper Mining Company to mine coal from his land in 2003, he didn’t expect his 30 acres would end up looking more like the moon’s cratered surface than Oklahoma prairie.

“My whole property is destroyed,” said King. “I used to have flat grassland. Now I’ve got a mountain so steep you can’t even drive around to keep brush off, and a ditch so deep if a cow fell in you couldn’t get them out of it.”

He was promised his land would be returned to its original state but instead, like many landowners in the southeastern corner of Oklahoma, his property was left ruined by mines dug and abandoned by Farrell-Cooper. The Arkansas-based company has mined coal in the area for decades, running up numerous violations of federal reclamation laws in the process.

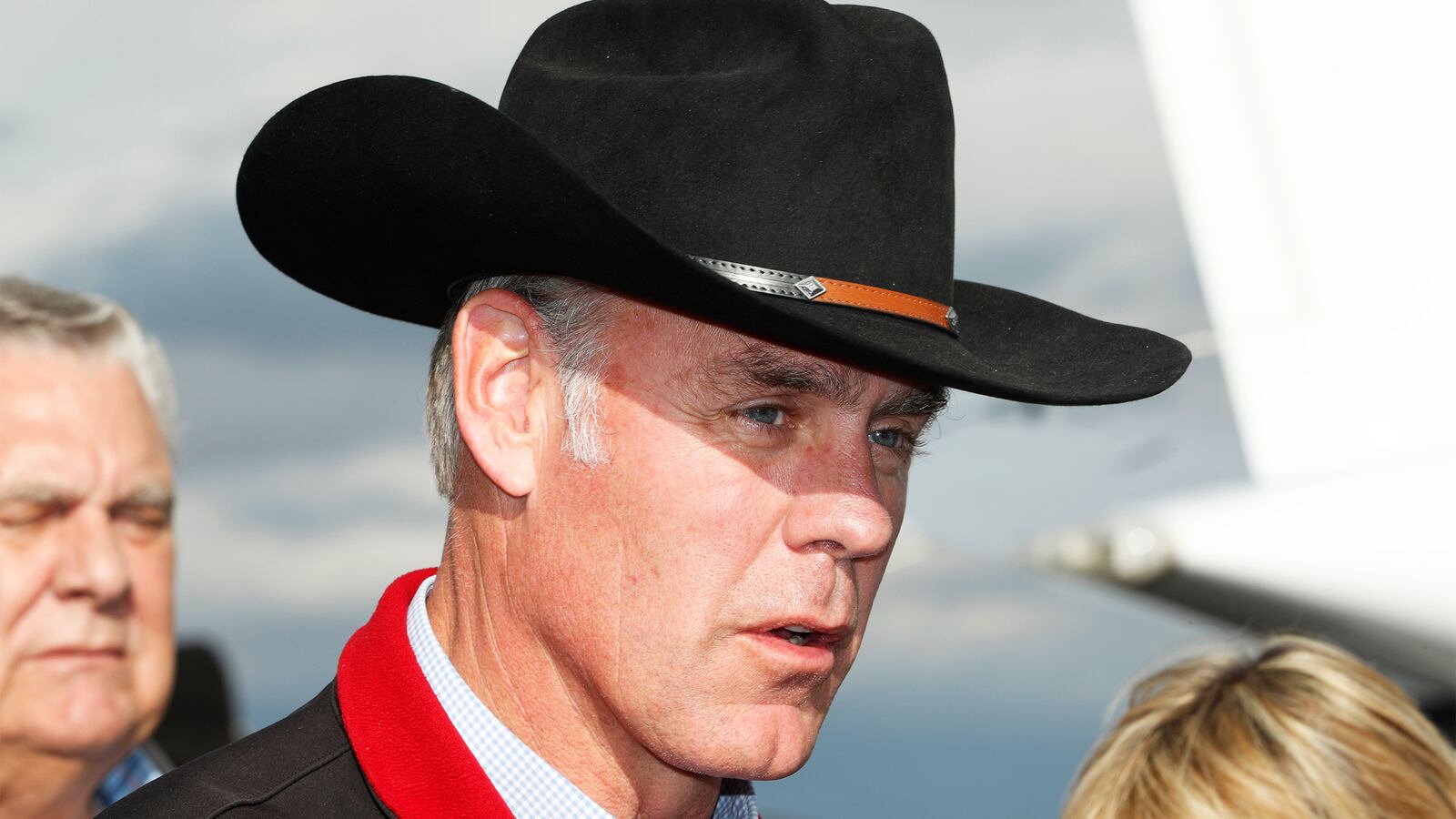

Now the landowners in this region who voted for President Trump overwhelmingly in 2016 must swallow the fact that the Trump administration—specifically, the Interior Department run by Ryan Zinke, represented in court by the Justice Department led by Jeff Sessions—has quietly dismissed violations that the last administration had levied against three of the company’s mines. The agreement comes after meetings involving several top Interior political appointees held specifically on the litigation in 2017, according to official calendars. The involvement of a number of political appointees, including many not in the department’s legal shop, in a long-standing, fairly low-profile legal dispute with a company is unusual, said former department insiders.

Farrell-Cooper’s long-standing battles with federal mining regulators culminated in a lawsuit filed against the Interior Department two years ago in retaliation for a 2013 violation for failing to rehabilitate the site of a mine. Farrell-Cooper’s prospects changed with the arrival of the Trump administration, however. In January, Robert “Bob” Cooper, the vice president of the company, told a Tulsa newspaper that a permit his company filed in 2010 with the Bureau of Land Management—another part of the Interior Department—to mine on federal land only moved forward after he met with Trump officials in April 2017. He said the officials asked how they could be helpful and that the mine permit followed soon after.

Cooper’s statement tracks closely with Interior leadership activity: In April and October 2017, Secretary Zinke’s political appointees met to discuss “Farrell-Cooper litigations,” according to schedules posted online. These appointees included Principal Deputy Solicitor Daniel Jorjani, previously an employee of coal company owners and Republican donors David and Charles Koch; Deputy Assistant Secretary for Land and Minerals Management Katharine McGregor, who worked as an oil industry lobbyist before serving several Republican offices on Capitol Hill; Associate Deputy Secretary James Cason, who has passed through the revolving door between the Interior Department and the energy industry since the Reagan administration; and policy adviser Landon Davis, who once worked for a pro-coal interest group.

Before the Trump administration, Cooper’s relationships helped the company garner support from politicians. In August 2012, then-Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt, currently the EPA administrator, wrote a letter to Interior Secretary Sally Jewell asking her to intervene on Farrell-Cooper’s behalf in its ongoing battle with Interior’s mining office. In June 2014, the Oklahoma congressional delegation sent a letter to Jewell demanding she look into whether the federal mining office asked the Oklahoma Department of Mining to sign a nondisclosure agreement keeping it from sharing information from others in the state, such as Pruitt’s office. In June 2015, four Republican committee chairmen from coal states, including Sens. Jim Inhofe and James Lankford, sent a letter to Jewell announcing an investigation of mismanagement at the mining office.

Interior press officials referred inquiries to the Justice Department, which declined to comment. Citing the advice of its attorneys, Farrell-Cooper declined to comment as well.

The decision to go easy on Farrell-Cooper appears to be one of the Interior Department’s latest moves in line with the current “Secretary of Interior’s Priorities,” referred to in a recent Interior Department watchdog letter to Congress. Those “priorities” were used to explain the sudden halt last year in funding of a study on health impacts from mountaintop coal mining.

A filing last month with the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Oklahoma shows the Interior Department and Farrell-Cooper agreed in March to settle the 2016 lawsuit. The settlement also dismissed two similar violations the company incurred with other mines in the area, including the one on King’s property.

Although the settlement requires Farrell-Cooper to make some minor changes to one of its mines, known as Rock Island, it essentially lets the company off the hook for the other violations, and some reclamation experts said it undermines laws requiring companies to clean up their mining messes.

“We had factual and legal proof that these were violations. That they should be vacated sort of makes me disgusted,” said Charles Gault, who represented the Interior Department against Farrell-Cooper for years before retiring in 2015. “There’s a race to the bottom with these regulatory programs. Once the snowball starts to roll down the mountain, it might get bigger and bigger.”

Farrell-Cooper, based just over Oklahoma’s eastern border in Fort Smith, Arkansas, has mined coal in Oklahoma for more than 20 years and generated federal violations for about as long, starting with a 1994 citation for leaving mountains of soil on privately owned land. Most of the violations charge the company with failing to fix the land it extracted coal from, a process called “reclamation.” Federal and federally approved state mining regulations say that after closing a mine, mining companies must leave the terrain around the mine in roughly the same state they found it in.

The company was founded by two families: the Coopers, Bob Cooper and William Cooper, who serves as the president of the company; and the Farrells, represented Charles and Patrick Farrell, who serve as company vice presidents.

At least one of its leaders is politically savvy. Bob Cooper donated more than $10,000 over the past decade to Oklahoma politicians at the state and federal level in addition to political action committees such as CoalPAC, the committee of the National Mining Association.

Federal regulators issued violations on two more Farrell-Cooper mines around 10 years ago. The company challenged the citations, which alleged that it with violated federal and state law for failing to reclaim the mining lands. In 2012, Farrell-Cooper was again charged with reclamation violations. This time, the Oklahoma Department of Mines (ODM) joined Farrell-Cooper in challenging the government, saying federal action overrode the state’s authority.

Federal regulators didn’t back down, and several judges backed the federal mining office’s decision. A 2013 Interior Department Inspector General report also found that reclamation law enforcement in Oklahoma “is not working as intended” and that federal efforts “have been met with strong resistance from the mining industry, ODM, and certain members of Congress.” Another Inspector General investigation that same year looked at allegations that a federal mining official “made a deal with the company to stall” the federal government’s “enforcement of Farrell-Cooper’s mining violations,” and that “employees of the Oklahoma Department of Mines (ODM) accepted gifts from Farrell-Cooper and provided preferential treatment in return.” The investigation wasn’t able to confirm the allegations.

Regardless, many residents have felt abused by the company.

“Farrell-Cooper is the biggest crook I’ve ever seen,” said Gary Williams, who inherited land from his father that abuts the Rock Island Mine. When miners excavated the land with explosives, some blasts were so strong they threw his family’s water heater off its base and killed several of their chickens, he said. When the piles of earth rose up, rain rolled off their sides and into the Williamses’ property, turning it into a swamp. Company efforts to fix the problem were insufficient, according to Williams.

“They said, ‘I promise you when we get this hill up here your land will be in the same shape it was when you started or better.’ Now it’s the worst it’s ever been. I’ve been out in the back yard in knee deep water trying to pull out all the weeds that grow in there,” Williams said.

Although Oklahoma doesn’t produce large amounts of coal, the coal it produces is particularly valuable because it can be used to make steel and other products. Modern methods brought more disruption, however: The method of pulling a line of explosives along a seam of coal, called “draglining,” creates a deep crevice with piles of earth on either side that can reach 100 feet in the air, resembling a small mountain range. Moving all that soil back into the ground requires more expensive and sophisticated equipment than tractors, and some mining companies will do anything to avoid the costs.

Oklahoma has long had a tense relationship with the federal government on coal. The 1977 Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, created in response to the devastation mining had wrought, made mining companies responsible for reclamation. Faced with opposition from coal companies, the government compromised by allowing states to obtain primary jurisdiction for enforcement subject to approval by the Interior Department. Interior’s mining office actually repossessed Oklahoma’s mining program in 1983 because it said state regulators were failing to enforce the act, and came close again in 1994 and 2010.

The recent settlement states that in exchange for nullifying the citations, Farrell-Cooper must abide by the existing permits for the three mines. Since the Interior Department had originally found those permits inadequate, however, that means little will change on the ground. It also says it will “address remedies” for drainage problems on Williams’ property and lower the main ridge along the Rock Island Mine, but since the land still won’t be anywhere near its original state, the violations will essentially be dropped. The settlement also contains a clause that the agreement can’t be used in future legal cases, but lawyers like Gault said it will set a bad precedent anyway.

“That may be true from a legal standpoint, but from a program standpoint, if you’re a mining official you can say, ‘Well, look, see what happened in Oklahoma? We can sign off on this in our state too,’” he said.

The lopsided nature of corporate vs. public interests in Washington is not lost on Oklahoma landowners who see few options for obtaining compensation for their losses.

“You can’t go after [Farrell-Cooper]—it would be cost prohibitive,” said King, citing the cost of filing a lawsuit. “If the federal government can’t get anywhere, then how are you going to get anywhere?”

“I’m not against the coal industry,” added King, who is in the oil and gas business. “I’d just like to have my hole filled up.”