In the spring of last year, investor and entrepreneur Bill Panagiotakopoulos got in a pickup truck in Cusco, Peru, and rode three hours up bumpy mountain roads to a tiny town near Machu Picchu. The sight of men in business suits was so unfamiliar that villagers in the rural town assumed he was part of the production crew for a movie that had just finished shooting. But Panagiotakopoulos wasn’t there for the scenery. As he looked out over the endless fields of coca plants—the plant most commonly used to make cocaine—he saw another kind of green.

“The fields are incredible,” he said in an interview this week from his hometown of Toronto. “The people are super friendly, and warm, and very progressive in their thinking—they want to make this a real business.”

“They want to evolve this farming that they’ve had for countless generations into the mainstream,” he added. “And we see the opportunity there.”

Panagiotakopoulos, 49, is the founder and CEO of Safe Supply, a Canadian company that invests in the future of the legal drug trade. The company, which has raised about $4 million in venture capital and went public last year, believes that the global surge in legalization policies will create a market worth hundreds of billions of dollars—one they plan to get in on at the ground level. Panagiotakopoulos and his backers are sizing up investments in drug-test strips, rehabilitation centers, laboratories, and any other product that may boom in a legalized drug market.

Bill Panagiotakopoulos in Peru.

Courtesy of Simply SafeUltimately, they want to own the supply chain for those drugs, too.

“There is going to be a day—probably sooner than later—where you can go buy drugs retail and actually not have all these poisons and have to deal with the underworld and the criminals,” he said. “That’s where the jump is from here to there.”

Panagiotakopoulos’ thesis—that widespread drug legalization is coming, and entrepreneurs should capitalize on it—is based on a global shift toward more liberal drug policies, and on his belief that our current system isn’t working.

A father of three, he insists that he’s not trying to get anyone hooked on drugs. (“I’m of the opinion [that] if you don’t do drugs, don’t do drugs,” he said. “And If you’re doing drugs, try to stop.”) But he also believes that prohibiting them is a waste of time—and of capital.

“The truth is, any 15-year-old in any major city—quite frankly, any city—in North America can go and get drugs anytime they want,” he said. “We’re just sending them to the criminals to go and get it.”

“Money’s being made every single minute of the day on drugs,” he added. “Just the wrong people are making the money.”

This business model is obviously controversial, and experts who spoke to The Daily Beast said creating a legal drug market is not as simple as Panagiotakopoulos suggests. But it has attracted attention from investors like Noel Biderman, the former CEO of the infamous affair website Ashley Madison.

Biderman, an expert in edgy business models, told The Daily Beast he was drawn to Safe Supply in part because of his experience watching friends and employees struggle with addiction. He said he grew frustrated with the stigma they faced and the lack of treatment options.

“It feels very reactionary, it feels very after the fact,” he said. “And so I’m always thinking about, ‘Isn’t there a better way to get out in front of this?’”

“So when someone comes to me with an investment thesis around, ‘These are the kinds of problems we want to solve,’ I’m interested,” he added. “Because I know it’s an incredibly difficult problem, but it can be solved. I believe that.”

—

Safe Supply is not Panagiotakopoulos’ first foray into the drug market. A serial entrepreneur, he said he founded a medical marijuana company called Beleave in 2015 after witnessing the drug’s effects on people with pain and anxiety. In 2018, when Canada legalized recreational weed, it became the 44th licensed marijuana producer in the country.

That same year, the British Columbia Securities Commission launched an investigation into Beleave for claiming to have raised $10 million in funding when it allegedly paid $7.5 million back to the investors through “prepaid consulting fees,” even though no consulting took place. In a 2019 settlement with the commission, the company admitted it had “participated in conduct that is abusive to B.C.’s capital markets” and pledged to change its ways. (Panagiotakopoulos noted that he was not named in the investigation and that it was “concluded to the BC securities satisfaction.”)

Bill Panagiotakopoulos inside a cocaine processing plant in Peru.

Courtesy of Simply Safe/Courtesy of Simply SafeBut the resolution of the securities investigation couldn’t save the company. Later that year, Beleave sold off a 23,000-square-meter, $6.7 million greenhouse in London it had bought just one year before. A month later, the company’s CEO, Jeannette VanderMarel, quit after just two months on the job, later explaining on a a podcast that she tried to focus on “ensuring that things were done properly and ethically,” but it “wasn’t received as well by some of the current people.” Asked to elaborate, she said: “Let’s just say there are shadows there.” (Panagiotakopoulos said VanderMarel was let go from the company and left “not on good terms.”) Beleave filed for bankruptcy less than a year later.

The experience did not dull Panagiotakopoulos’ enthusiasm for legal drugs. Even as Beleave was breaking down, he was throwing money into the latest drug to be decriminalized in some areas: psilocybin. He invested “heavily” in experimental drug companies like MindMed and Cybin, and launched his own mushroom-based startup: Rekemend, a “Mushroom MultiVitamin Superblend” that claims to aid in weight loss, hair growth, and seasonal allergies. (The product is available for purchase on Amazon, but the company’s website has been suspended and has not posted on Instagram in over a year.)

He launched Safe Supply in 2022 and the company went public late last year, in an attempt—as Panagiotakopoulos loftily described it in an email—to “democratize access to investing in ending the war on drugs.” Like Beleave, its trajectory has been less than smooth: Following an initial valuation of $8.6 million in October 2022, the stock price plummeted to less than half its original value within a month. As of press time, it hovered around 25 percent of its original price. Panagiotakopoulos attributed the decline to an overall contraction in the Canadian venture market and said he believed it would be “corrected by this summer.”

There have been a few successes: The company recently acquired a 7 percent stake in Safety Strips, which manufactures test strips to check for fentanyl in recreational drugs. Panagiotakopoulos is fond of noting that, mere months ago, simply carrying a fentanyl test strip in the United States could get you arrested. Today, more than 40 states have legalized the product—a development Panagiotakopoulos hopes will make using street drugs safer, and help prove his investment thesis.

Vending machines in Brooklyn disperse fentanyl test strips and naloxone as well as hygiene kits, maxi pads, Vitamin C, and COVID-19 tests.

Spencer Platt/Getty ImagesThe company also recently touted what it called a “landmark” shipment of decocainized coca powder and extract from Peru to its offices in Canada, which it hopes to study for possible medical benefits. Its website pitches a variety of uses for the extract, from energy drinks to pharmaceuticals to “functional foods.”

But Panagiotakopoulos doesn’t want to linger in the land of test strips and coca extracts—he wants to deal in the real thing. That’s why he’s invested in CannaLabs, a startup with a dealer’s license in Canada, which allows him to order and perform research on otherwise illegal drugs. He’s seeking similar licenses in the U.S. and South Africa and is looking into selling MDMA in Australia, which started allowing doctors to legally prescribe the drug for PTSD and depression last year. Asked if his ultimate goal is to sell cocaine legally, he replied: “Of course!”

“If I had a contract to supply Amsterdam and Bern and British Columbia with cocaine—which by the way, we do have a track for it out of Peru—it would be a multibillion-dollar company,” he said.

Not everyone is excited by this proposition. Jonathan Caulkins, a professor of operations research and public policy at Carnegie Mellon, said that prohibiting substances does in fact decrease usage—a trend that holds true whether you’re talking about alcohol, marijuana, or personal fireworks. The liberalization of laws around cannabis in the last 30 years led to a tenfold increase in the number of daily and near-daily cannabis users, he said. And opioids are far more dangerous drugs than marijuana.

“We had a lot of people overdosing and dying when the opioid of choice was prescription opioids,” he said. “And that was about as regulated as you were gonna get.”

Keith Humphreys, a psychiatry and behavioral sciences professor at Stanford, also referenced the opioid crisis to point out flaws in Safe Supply’s model.

“I think the Sackler family proved through Purdue Pharma that if you can dramatically increase the supply of addictive drugs, you can make an extraordinary sum of money,” he said, referring to the makers of the painkiller Oxycontin. “You have to addict and kill a lot of people in the process, but you do make a lot of money.”

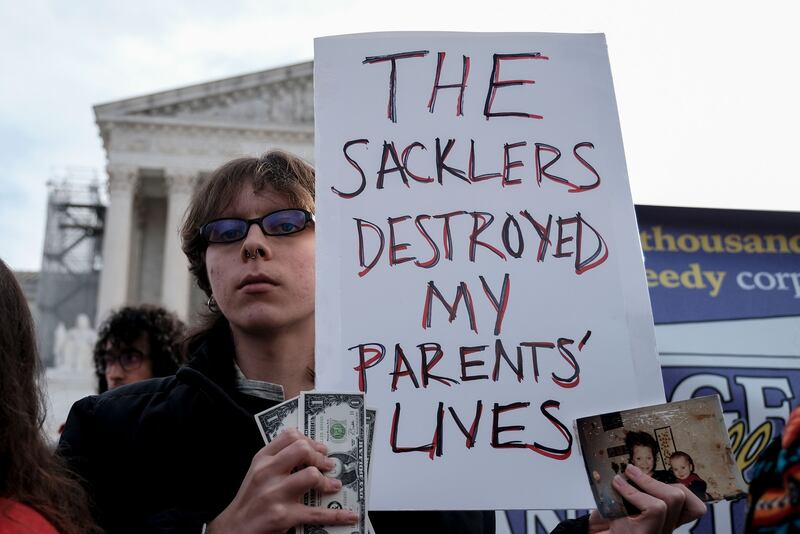

Aden McCracken Tyrone of Pennsylvania outside the U.S. Supreme Court as the court hears arguments regarding a nationwide settlement with Purdue Pharma, the manufacturer of OxyContin.

Michael A. McCoy/For The Washington Post via Getty ImagesHumphreys said it was not uncommon for the investor class to favor drug legalization because they see it as another way to make money. He pointed to tobacco, which before the 1900s caused only seven recorded cases of lung cancer. Then businessmen figured out how to cure the tobacco to make it taste sweeter and able to inhale more easily, causing a faster dopamine hit to the brain. Cigarette addiction skyrocketed.

If drugs like cocaine, heroin, and MDMA are legalized, he said, there would be nothing stopping savvy businessmen from making them even more addictive, driving down the price through mass production, and spending billions on advertising.

“[Drug] legalization means corporations, marketing, lobbying, all the things the tobacco industry does,” he said. “And that dramatically increases use, which increases death and addiction.”

“No customer like an addicted customer,” he added.

Despite all this, the biggest risk Safe Supply poses may not be to consumers, but to its own investors. The legal drug industry is nascent and, despite what Panagiotakopoulos may believe, not guaranteed to take off. Backlash to the legalization movement has already started, and some jurisdictions are choosing to roll back their policies rather than push forward.

Lawmakers in Oregon, for example, voted earlier this month to rescind some decriminalization efforts, making possession of a small amount of drugs a misdemeanor once again. Drug deaths in British Columbia have continued to rise since the province decriminalized some drugs last year. Even Portugal, the country long touted as a prime example of the benefits of decriminalization, is experiencing a surge of drug use and drug-related crime.

Caulkins, the Carnegie Mellon professor, said investors in Safe Supply may be too far ahead of the curve.

“Their risk is that the movement towards opening up these markets happens so slowly that they don’t really have enough investment opportunities for their partners,” he said.

That seems to be a risk Panagiotakopoulos is willing to take. He ended our interview this week abruptly at the scheduled end time, with several questions left to go. He had yet another startup to meet with.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to reflect that Jonathan Goldman and Steve Arbib and not current investors in Safe Supply.