When Rep. Carolyn Bourdeaux was gearing up last spring for a primary battle against Georgia Democratic incumbent Rep. Lucy McBath, Bourdeaux’s campaign team flagged an alarming article in Politico for her to read.

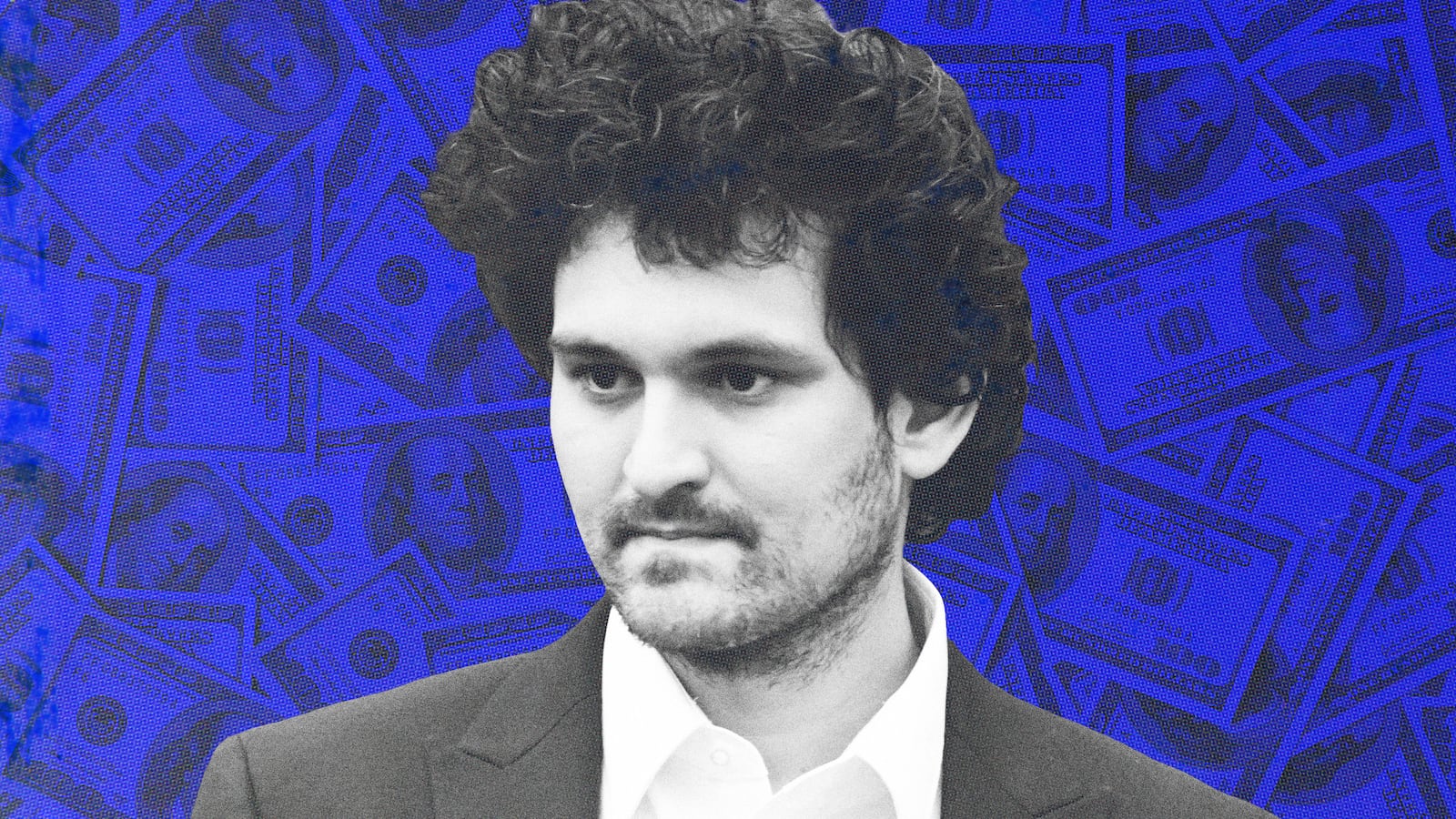

It reported that Sam Bankman-Fried, a twentysomething cryptocurrency billionaire, was making his foray into politics as a Democratic big-money player—and he was starting with a seven-figure campaign to re-elect McBath and defeat Bourdeaux.

“We had no idea until we saw that story. It is a huge shock to see that kind of money come in against you,” Bourdeaux told The Daily Beast. “For a candidate like me, who raises money doing call time, that is equivalent to one year’s worth of labor that he’s able to match with a stroke of his pen.”

Soon after, nearly $2 million worth of TV ads from Protect Our Future PAC—which touted McBath’s inspirational personal story and positions on health care and Social Security—began blanketing the airwaves in suburban Atlanta. The ads, among the first of the race, helped introduce McBath to a newly drawn district that was home to few of her prior constituents. Bourdeaux, already considered an underdog in the race, struggled to pick up traction. She lost in a landslide.

Six months later, McBath is preparing for a third term, Bourdeaux is leaving Congress, and Bankman-Fried is in federal custody, likely facing a number of criminal charges.

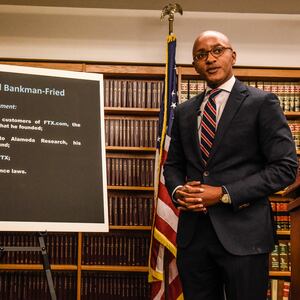

The collapse of Bankman-Fried’s company, the cryptocurrency exchange FTX, has revealed that his deluge of campaign cash wasn’t just shady—it may have been stolen. Federal prosecutors for the Southern District of New York allege that Bankman-Fried directed “tens of millions” in illegal campaign contributions using the money customers had deposited in FTX’s platforms to grow their savings, not fund political campaigns.

Among the charges federal prosecutors are pursuing against Bankman-Fried are campaign finance violations. Court filings have suggested evidence that he spearheaded an illegal “straw donor” scheme where other individuals contributed his money in their names.

In response to the news, many entities that received checks from FTX have either donated those funds to charity or set them aside in the event they are reclaimed in some kind of legal proceeding. FTX executives gave tens of millions of dollars directly both to Democratic and Republican candidates and organizations, with Bankman-Fried himself claiming that he obscured his contributions to the GOP in order to evade scrutiny.

But when it comes to Protect Our Future PAC, that money is long gone. The TV ads his money funded ran months ago, but their impact will long endure. In the 2022 cycle, the PAC spent over $24 million in 18 House Democratic primaries around the country, and 14 of the candidates it backed will be serving in the House next year.

The list includes Rep. Shontel Brown (D-OH) and soon-to-be Reps. Robert Garcia (D-CA), Jasmine Crockett (D-TX), Maxwell Alejandro Frost (D-FL), and Morgan McGarvey (D-KY), all of whom received at least $900,000 in outside spending from Protect Our Future PAC.

Ironically, the Democratic candidate Bankman-Fried spent most to elect, the crypto-adjacent Carrick Flynn, ended up losing his primary in an Oregon district. Protect Our Future PAC dropped more than $11 million on that race.

In many of these races, it’s impossible to quantify exactly how much Bankman-Fried’s spending contributed to their endorsed candidates’ victories. But it’s clear he had a significant impact, through strategically timed ad buys, slick messaging, and—in at least one alleged case—backchanneled threats to a rival candidate.

“In a House primary, a million dollars is a tremendous amount of money,” said one Democratic campaign consultant, who was not authorized to speak publicly on Bankman-Fried’s efforts. “It immediately sets you apart.”

Come January, there will be a caucus of lawmakers on Capitol Hill who, if they don’t owe their seats entirely to Bankman-Fried, at least saw their paths to power paved with stolen, illegal campaign contributions.

“It’s hard to think of a historical parallel where there was not only massive amounts of political spending, but some or all of that spending was illegal under campaign finance law and it was all done with stolen money,” said Adav Noti, senior vice president of the Campaign Legal Center. (CLC, a nonprofit, received a $2.5 million donation from Bankman-Fried, and has since put the funds into a separate account to be accessed in FTX-related legal proceedings if needed.)

Given that it is illegal for super PACs and candidates to directly coordinate or communicate, there is plenty of room for candidates Bankman-Fried helped to distance themselves from his money, said Jordan Libowitz, communications director for Citizens For Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, a watchdog group.

“We don’t have a lot of precedent for people trying to disavow spending outside of their own campaign that’s helped by someone who’s now controversial,” Libowitz said. “As for grappling around it, that requires a certain amount of shame, which is in short supply with members of Congress.”

In two especially contentious Democratic primaries, the candidates who were on the other side of Bankman-Fried’s spending have watched with outrage—and a dash of validation—as the onetime crypto baron has spectacularly unraveled.

A former budget analyst for the state of Georgia, Bourdeaux had been skeptical about the crypto industry from the beginning. “Any time you see the words ’29-year-old billionaire’ and ‘chartered out of the Bahamas’ in the same sentence, it should raise some red flags,” she said. But she added she didn’t expect the “twist” that ultimately came.

After Bourdeaux learned of Bankman-Fried’s intervention—the second highest sum he would spend in any race—in favor of McBath, she and her campaign aides debated how to respond. “Within my team, they were like, ‘Oh God, don’t call this out, he’s got over $20 billion. The minute you start to make a stink about it, he’d drop $10 million on the race,’” she recalled.

But Bourdeaux did publicly criticize Bankman-Fried over his involvement in the primary. Afterward, she received a warning from the billionaire through a third party, according to a source familiar with the race. The person made clear Bankman-Fried would gladly spend more if the congresswoman continued speaking out against him. (Bankman-Fried did not respond to a request for comment for this story.)

In the end, Bankman-Fried did not spend more to unseat Bourdeaux. He did not need to: McBath was the beneficiary of another $2 million in outside backing from Everytown For Gun Safety, the organization where she previously worked. Bourdeaux, meanwhile, got $0 in outside backing. Beyond that, McBath—whose background and views are well known in the state—may have been a better political fit for the new district than the centrist Bourdeaux, given the increasingly liberal character of the Atlanta suburbs.

Ultimately, Bourdeaux lost by 33 points. In such a blowout, it would be hard to claim that Bankman-Fried’s involvement sealed the outcome. Bourdeaux makes no such argument, but she did explain how helpful the deluge of glossy introductory ads was for McBath.

“What [the ads] allowed her to do was get on TV one month before I could contemplate getting up,” Bourdeaux said. “She is a celebrity, but she was not known as being the congresswoman from that area, and this was helpful in establishing her early on in the race.”

McBath’s campaign did not respond to a request for comment, but when The Daily Beast twice confronted McBath about Bankman-Fried’s donations in November, McBath remained silent as we repeatedly pressed her about returning the $2,900 the crypto billionaire contributed directly to her campaign.

Meanwhile, in an open primary for a safely Democratic seat based in North Carolina, Protect Our Future PAC spent over $1 million to boost a more establishment candidate, state Sen. Valerie Foushee, over Nida Allam, a Durham County Commissioner and former organizer for Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign.

“It was pretty early on that we’d heard whispers of this crypto billionaire dude,” Allam said in an interview with The Daily Beast. “At that time, we were just hearing about them as the crypto bros, they had created a PAC and they’d started investing in some races.”

Later, they learned that Protect Our Future PAC’s stated focus was to elect candidates who would push for legislation to improve the country’s ability to prevent future pandemics, a popular priority within the “effective altruism” movement Bankman-Fried moved within. His brother, Gabe, led a nonprofit called Guarding Against Pandemics that advocated the same goals, and he also contributed hundreds of thousands of dollars to political candidates and committees.

Allam recalled her team was skeptical “at the very beginning” of that stated motive for Bankman-Fried’s deluge of spending. That skepticism deepened when they found out he had endorsed Foushee. While Foushee had favored COVID-19 response measures while a state legislator, Allam served on Durham County’s public health commission who was vocally on the front lines of the local effort to respond to the pandemic.

“It just didn't add up,” Allam said. “This work of mine is very public.”

In Allam’s camp, their thinking was that merely keeping the “crypto bros” out of the race would amount to a victory. When Foushee was ultimately endorsed, they expected to see heavy spending, but they weren’t sure how much.

Through the primary, Protect Our Future PAC spent just over $1 million on ads that were similar to those that boosted McBath. “Valerie Foushee has served our communities her entire life,” one spot said, touting her record as a public official and promising she would fight for voting rights, a woman’s right to choose, and expanding Medicaid access.

As was the case with McBath, Foushee also benefited from the involvement of other outside groups. Her biggest backer wasn’t Bankman-Fried but instead AIPAC, the powerful pro-Israel organization, which spent over $2.1 million supporting Foushee through a PAC called United Democracy Project.

Ultimately, Foushee won by nine points. Allam argued that it might have been much closer had Bankman-Fried not spent so heavily. “The polling showed that this race was always very close,” she said. “We raised more money than our opponent from small dollar contributions. We spent less per vote than our opponent had to spend for this election.” Foushee’s campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

Like many Democrats, both Bourdeaux and Allam are grappling with the implications of Bankman-Fried’s impact and what it means for the party and for the political system more broadly. Those who benefited most from Bankman-Fried’s largesse will be under the most pressure to support whatever measures Congress takes to hold him accountable. McBath and Foushee have made no public statements so far on that front.

But others have: Maxwell Frost, the 25-year old congressman-elect who was a beneficiary of the former billionaire, tweeted that it “seems clear that Sam Bankman-Fried cheated and conned over a million people out of their money” and argued he “should be held accountable.”

Allam suggested Democrats should have thought more carefully about Bankman-Fried’s influence, even if it wasn’t clear yet the extent of his potential wrongdoing.

“Not just with my race, but all of the races he was involved in, we’re seeing that people are now going to Congress through the use of stolen money that was laundered through super PACs,” Allam said. “That’s what sent people to Congress all across this country. I think as a Democratic Party, we should have been better.”

“Anyone who had taken his support, and accepted it, and didn’t condemn it during their campaigns, they do have that obligation to the people of their district, to the people of this country, to the people who were defrauded,” she said.

Bourdeaux made a similar point. “There’s no way someone can pay back millions spent on their behalf by a super PAC,” she said. “But acknowledging that you are heavily supported by what was really shady money would be important, and then laying out what you’re going to do to make sure that kind of thing doesn’t happen again.”

“The bigger picture here is,” she said, “this is very challenging for your democracy if you have lots and lots of members who owe their careers to very wealthy businessmen.”

Unless Congress backs campaign finance reform to rein in unlimited outside spending, more scandalous episodes like Bankman-Fried’s will happen, experts say. But shady corporate money is leveraged to back lawmakers all the time, CREW’s Libowitz says—they just don’t “crash and burn so epically” as the former crypto baron.

“There are a significant amount of members of Congress who are there because they had major financial backers that you never hear about,” he said. “There are probably a lot of people breathing a sigh of relief in Congress that the people backing them, who put them in office, have a little more discretion.”