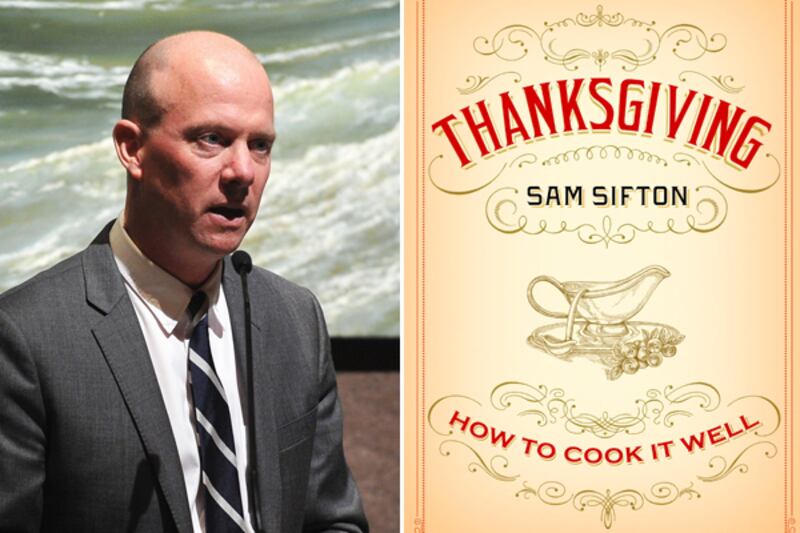

With November upon us, and Thanksgiving looming a mere three weeks away, it’s time to talk turkey. Professional chefs and amateur cooks alike will be poring over recipes, debating the finer points of dressing vs. stuffing and sweet potatoes vs. mashed, and agonizing over whether to serve pumpkin pie or pecan (correct answer: both). Crises are sure to arise. But this year, just in time to combat the pre-Thanksgiving jitters, former New York Times restaurant critic (and current national editor) Sam Sifton has released the ultimate guide to making a feast for the ages. Thanksgiving: How to Cook It Well—offering a wealth of favorite recipes and written in the erudite, sparkling style that won Sifton plaudits during his critic days—tackles the perennially thorny issues of how best to cook the bird, how to set (and seat) a proper table, and the secret to a really great gravy. Here, Sifton shares some Turkey Day tips, gleaned from years of holiday expertise and a stint on the Times Thanksgiving crisis hotline.

How many years did you spend manning the Times Turkey Day hotline?

I guess I did it for two years—it runs together, of course, because once you do it once, people are asking you about Thanksgiving all year long. I found it to be a really enjoyable experience, a pretty cool duty. It’s always been an important holiday to me, and I think it’s a hugely important holiday in America, because it’s our one shared, secular feast. We have other national holidays that are not religious in nature—the 4th of July, for instance—but the 4th of July … doesn’t have that kind of sacramental feel that most Thanksgivings do. And that really became clear for me when I was sitting at my computer taking e-mails and tweets and calls and messages from readers literally all over the globe, looking for help. And the help was sometimes modest—they didn’t know to make a gravy that wasn’t lumpy—and sometimes quite severe: how do you cook a turkey in Mumbai?

You mention that in the book—the tandoori turkey.

I was amazed they were able to get the turkey … [I told] them to think of it as a big chicken. That’s really all it is from a cooking point of view. And so having done this for a couple of years, it occurred to me that it might be helpful to have a kind of Hoyle’s book of rules—not for card games but for the holiday itself. And so I thought if maybe I could lay down some very basic rules and recipes for Thanksgiving, it would allow anyone—whether new to the country or familiar with the holiday—to create a meal that, in my mind, would be correct [and] would live up to the ideals of Thanksgiving … set down in our collective imagination by that Norman Rockwell painting Freedom From Want.

There should be a big, beautiful burnished golden bird and there should be copious numbers of side dishes and the table should be set and that the children should be spit-shined and polite. And it against that image that so many of us come up short and worry. And the overwhelming message that I took from my time on the helpline was that people worry about this holiday. And I wanted to alleviate some of the stress that accompanies the making of this feast.

We do worry about it—and it’s silly, because we do it every year. And yet we still worry.

Serving a dozen people or more in your home is something that most Americans are prepared to only experience on Thanksgiving. So it puts a lot of weight on the meal and I think a lot of people find themselves caught up in the throes of the thing and realize that they don’t know how to set a table, or that their bird is always dry, or that they don’t understand the principles of social dynamics that would occasion them to assign seats rather than just let people sit where they want. And if we can talk about that plainly and with a fair amount of comfort attached to it, I think the stress level can go down and we can get back to what the holiday is supposed to be about, which is the giving of thanks.

So what was the craziest Turkey hotline conundrum that you ever had to handle?

I got a lot of people, more than you would imagine, writing in on Thanksgiving morning to ask me what to do with their frozen turkey.

Oh no.

And the answer to ‘What can you do with a frozen turkey on Thanksgiving [morning]?’ is ‘Not much.’ There’s not much to do. You’re going to eat late. And it really struck me as an example of how ill-prepared some people are to create the holiday and how unfamiliar they are with the science of cooking.

How far in advance should a cook start?

I think that it’s never too early to start sketching out your plans. But for sure, the weekend before Thanksgiving—the Saturday and Sunday before the Thursday of the holiday—is a big and important part of preparing for the feast. There’s a lot you can do then, particularly if you have a freezer that can take a few things. You could make a stock ahead of time, you could make stuffing ahead of time, you could make pies ahead of time and freeze them. You could start laying in the supplies that you need to get—your turkey, for instance, might arrive on the Sunday and be ready for brining on the Monday. Or if you’re not brining it, it could just be defrosting slowly and getting ready. You gotta buy those potatoes, you want to lay in the butter. On that weekend, when you have a moment to run to IKEA or call your aunt or whatever, you want to determine, ‘Do I have the tools I need to pull this off?’

When you handled the Turkey hotline, were you still able to cook the big dinner or did you have to outsource it?

I didn’t really outsource it, because it was my family making the holiday, but the one thing I was sad about and wistful about was that I wasn’t cooking the Thanksgiving for those years. They were nice to me, they let me make the gravy when I got back—that’s generally the last thing that’s made—and I think I made a few things before going off to work. I made the cranberry sauce in advance, and a couple other things like that. But it was weird. And it was kind of marvelous in a way, not to cook for those two years. I think one of the things that I learned about us, as Americans, during those years was that there is this special group of people who work on Thanksgiving day.

I’ve been one of them—I used to work in a restaurant.

There are restaurant workers, and cops and firemen and nurses and doctors, there are newspaper people, there are the guys slinging coffee, and the conductor on the subway … It’s really kind of neat to be footstreaming through, in my case, New York City, on Thanksgiving day with purpose—to know that you’re going to go and help people get through. I mean, most people who are working on Thanksgiving Day are doing so because they’re providing a service to others—whether that service be food in a restaurant, or news in a newspaper, or first response in the case of the ambulance driver or EMT, or firefighter or cop. And there’s a kind of fraternity that develops out of that, that isn’t spoken, but is understood on the street. And I kind of dug it. That said, now that I’m done doing that, I’m really looking forward to roasting a bird with my family and having a day off and really enjoying it.

I’m sure. In the book, you explore brined turkeys, butterflied turkeys, spit-roasted turkeys, grilled, deep-fat fried. What’s your favorite way to cook a turkey? Or alternatively, what are you going to do this year?

Well, we have a lot of people come. So oftentimes we make two turkeys. And because, like most people, my oven is too small, and I only have one of them, I’m not going to roast both of them. I’ll probably roast one of ‘em and fry one…the fried turkey seems like a parlor trick, a Southern gentleman’s parlor trick, but in fact it yields a really, really good turkey. And except for the initial problem of getting the equipment that you need to do it, and the perennial difficulty of how you dispose of the oil at the end of the process, I really think it’s a great way to cook a turkey. Not necessarily a giant, 20-lb. bird, but a good 15-16-lb. bird in peanut oil is just amazing. You know, just to put people’s minds at ease, there’s no absorption of oil—it’s not a greasy thing at all.

I would have thought that it would be greasy...

No—because where’s it going to go? And the fact of the matter is, what you’re doing is you’re putting a very dry bird—you gotta really let it get dry; I don’t want any moisture on that thing, there’s no batter, there’s no flour, there’s nothing on it, it’s just the bird—and I’m immersing it into incredibly hot oil, where it almost instantly seizes up. It creates a blister, essentially, around the entire bird, and that’s it. Where’s the oil going to go? It is just transferring its heat to the interior of the bird and it’s doing so in such a way that the juices of the bird have nowhere to go. So when you pull it out, and let it drip, and remove it to a sideboard to sit, as you would a roast turkey, for 20 minutes or half an hour, there’s nothing greasy about it at all. It just looks like this beautiful fried thing.

Are there specific Thanksgiving dishes that you think should always appear on regional tables in the South, or New England, or Texas? You mentioned that you serve oysters [at your family’s meal]. I’m a West Coaster, so to me that sounds very East Coast.

Where in the West Coast are you from?

I’m from Washington—though we do have lovely oysters there, too.

Oh yeah, I would definitely put oysters on that menu. Man, oh absolutely. Those are so beautiful up there. But Washington State, Oregon, you guys have a totally different larder from ours.

Very different—many people would do salmon for Thanksgiving, which may sound untraditional. But for the Northwest, it’s very traditional.

Absolutely it’s traditional, and there’s nothing wrong with it. I could see bringing, like, a salmon jerky into a stuffing or dressing, and just using a really kind of aggressively smoked salmon like we use bacon on the East Coast. I presume that everybody dries morels up there.

Yeah, the mushrooms are amazing.

The Pacific Northwest has a very involved and excellent mushroom scene, and that should show up on Thanksgiving tables [there]. You know, for such a doctrinaire, or apparently doctrinaire person, I really do believe that the traditions that you bring to your table, or that were brought to your table by your mother, father, grandparents, or cousins, or friends, matter, and they should not be banished. I think there are exceptions to this rule—I don’t think that there’s any time you should put a napkin in a wine glass, that’s just crazy talk. [But] I think cooking within the larder of your tradition, or the larder of the region that you’re from, is a good idea.

Can we talk about turkey stock? I loved that your book demystifies it. For a lot of people, they hear “stock” and they think of a long, simmering, French thing—and you reveal that it’s actually quite easy to make.

Literally the first thing you ought to do on Thanksgiving morning is put that [turkey] neck into a pot with water and some vegetables and let it go. Because it will create an okay turkey stock that will help you and will be invaluable—and indeed, will get better—throughout the day. That’s just standard operating procedure, and very simple. I would not enter that stock into a stock competition, but it is nevertheless an easy and excellent way of providing moisture to various things that you’re cooking throughout the day. Then, the very last thing that you’re going to do at the end of the whole Thanksgiving process is take the turkey carcass that remains from your feast and make that into what will be a much, much richer and more delicious stock.

If you believe, as many people do, that you ought to start the day with a stock of that quality, well, that’s another thing you can add to your weekend tasks. At the supermarket, you can buy a couple of turkey wings for not that much money, and you can throw those in the oven—I have a recipe for this in the book—and roast them and get them nice and caramelized and super-flavorful, and use that as the basis for a more serious turkey stock. I don’t want to over-complicate things for people. They get a little freaked out—like, ‘I’ve got to buy turkey wings, now? Turkey legs? The weekend before, to make a stock that seems to complicated and scary?’ That’s fine—do it with the neck on the day of. It will be perfectly acceptable.

In terms of a good gravy—we’ve talked about turkey stock. But what makes the difference? Is it the extra fat? Or the attention that you have to pay to it?

We can make a lot of hay about the loving attention. But … let’s say you’ve arrived from Mars, you’ve discovered that there’s this Thanksgiving holiday, you’ve seen this book (or better yet, you’ve purchased a couple copies) and you’ve roasted this turkey according to my specifications, and this turkey is resting on a board, and you’re looking at the pan that you cooked this thing in. And there, at the bottom of the pan, is everything you need to make a great gravy. There’s an enormous amount of funk, and turkey fat, what’s called fond, which looks like the crispy, brown, dark bits—and [you can add] that stock, a little flour, some salt and pepper, maybe some cream, maybe some booze—but the key is, you’ve got that funky, fat stuff at the bottom of it. And that’s going to make your gravy.

Would you describe yourself as a Thanksgiving purist?

Sure—I am a Thanksgiving purist. The fact of the matter is, if it’s my job to say “Here’s how to make Thanksgiving, and here’s how to cook it well,” then there’s going to be a turkey. And there are going to be some side dishes. And the side dishes are going to be mostly true to the American larder as we understand it. Which is of course made up of thousands of different experiences and hundreds of different national cuisines as people develop their own experience. But in my mind, let’s just keep it basic. You don’t need to make garlic mashed potatoes. That’s a step too far. Just make good mashed potatoes and everything will be great.

Don’t over think it.

Don’t over think it. Let’s make the traditional, classic, purist’s Thanksgiving. And then you can move on from there. But if the idea is “I’m going to step up to the plate and immediately do something different,” I don’t think that serves the holiday. I don’t think that serves your friends or family. I think that’s kind of experimentation for experimentation’s sake, and it forces people down into the trap of fashion. Most people are getting their ideas for Thanksgiving from us, that is to say, from the media. And if you’ve spent any time at all—and you have, and I have—working in food media, Thanksgiving arrives every year, and with it, the tyranny of hip. You have to come up with a new way of doing the turkey, a new way of doing the side dishes, a new way of making pie. And that kind of relentless pursuit of the new thing leaves a lot of people stuck without a real understanding of what the basics are. And the real freedom of writing this book … is that I’m not constrained by that need. I don’t have to tell you, ‘Here’s how to make wasabi-dusted turkey.’

Or a star-anise turkey.

Yeah, I don’t have to do that. I can say, “Here’s how to make a roast turkey. Here’s how to make mashed potatoes. Here’s how to make dressing and green beans. Here’s how to make butternut squash and sweet potatoes.” And that, I hope, will be something that people want. There are not a lot of outlets giving them that instruction. Because everybody else has to figure out the new way of doing it. Although if I were assigning right now, I would totally do the Pacific Northwest. I really would. It would be awesome.

It would be a beautiful meal.

I mean, seriously, we could do that right now. You’re on the Pacific Rim, they’ve got all that Asian stuff coming in. You could do fermented black bean sauce … I don’t think I would do a salmon at the center of the table, I think I would still have a turkey. But I might, as I said, use that salmon candy or smoked salmon in something.

Yeah, the salmon bacon is a great idea.

Yeah, man.

One of the chapters I found really touching was when you talked about a certain meal—you were out on Long Island, and you really had nothing [fancy], but there was that moment when the table was set, and people came in, and it was suddenly like, ‘Oh, here’s the holiday!’ In the restaurant business, we used call that “showtime”—you’re putting on a production for the people you love.

You are—and not to be too ridiculous or spiritual about it, but the analogy is not so much to restaurants… [but] more potentially controversial, which is to say, church. Or temple. Or the place of worship. The ritualized sharing of the meal—to the end of giving thanks for the bounty of the harvest, and the reality of your friendships and relationships—really means something. And is heightened in some way, in my mind, by the presence of a sacrament. The table is set in a particular way, for a particular purpose. And it can … almost take away your breath. There are candles glinting, and there are flowers, and there’s the expanse of clean, white tablecloth. And it’s pretty neat. And you shouldn’t deny yourself that. And you shouldn’t deny your guests that.

And part of the power of ritual is the comfort of knowing that you’ll get to experience it again, in a similar way to the way you did before.

People freak out about change. That’s the countervailing issue here. The food media is telling us, the media is telling us, culture is telling us every year: “You have to make it new and different.’ And your friends and family are saying everyone year, ‘I want it the same. I want it exactly the same.” And it may be that they’re saying, “I want it exactly the same as when I was eight, when my grandmother made it.” Or they’re saying, “I want it exactly the same as it was last year.” And it never will be exactly the same. The social dynamics will be different because your father is now dead … or because those people didn’t get married, they broke up … or because your kids aren’t two any more, they’re 11. And the turkey will be different because you decided to fry it this year, and that’ll tick off the people who like the roast bird. But maybe the mashed potatoes will be exactly the same. Or maybe the things that you put on the table will be exactly the same. And if you believe that that doesn’t matter, you’re nuts. It does matter. You may not know to whom it matters, but for sure it matters to someone at the table. And I think we owe it to the holiday to at least have these through-lines.

That’s a great way to put it. Speaking of rituals, one my favorite rituals is the Times wine panel. You mention in your book that your family has gone through all these different beverage phases—the Barbaresco phase, the hearty American Zinfandel phase. What’s the phase you’re in right now? What do you think will be the correct wine this Thanksgiving?

I think the most important quality in Thanksgiving wine is that there be a lot of it. I think we oftentimes get too tied up in whether Barbaresco is the perfect match, or whatever, and not enough time thinking, golly, this seems excessive, but it’s an excessive holiday. That said, I find myself this year thinking—I mean, it’s a little early to plan, but never too early to plan—and I’m thinking some Brouilly’s are probably going to be the way to go. Some Brouilly’s with some chill on them. That would be sick.