JFK's brother-in-law fought to realize Camelot's promise all of his days. Adam Clymer on how Shriver helped shape a country—and never lost his enormous enthusiasm for it. Plus, George McGovern on Shriver's "boundless heart" and John Coyne on how Shriver built the Peace Corps.

Robert Sargent Shriver did more than any other New Frontiersman to heed his brother-in law's famous call: "My fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you. Ask what you can do for your country." In the Peace Corps and then the War on Poverty, he led thousands of Americans in taking up that challenge.

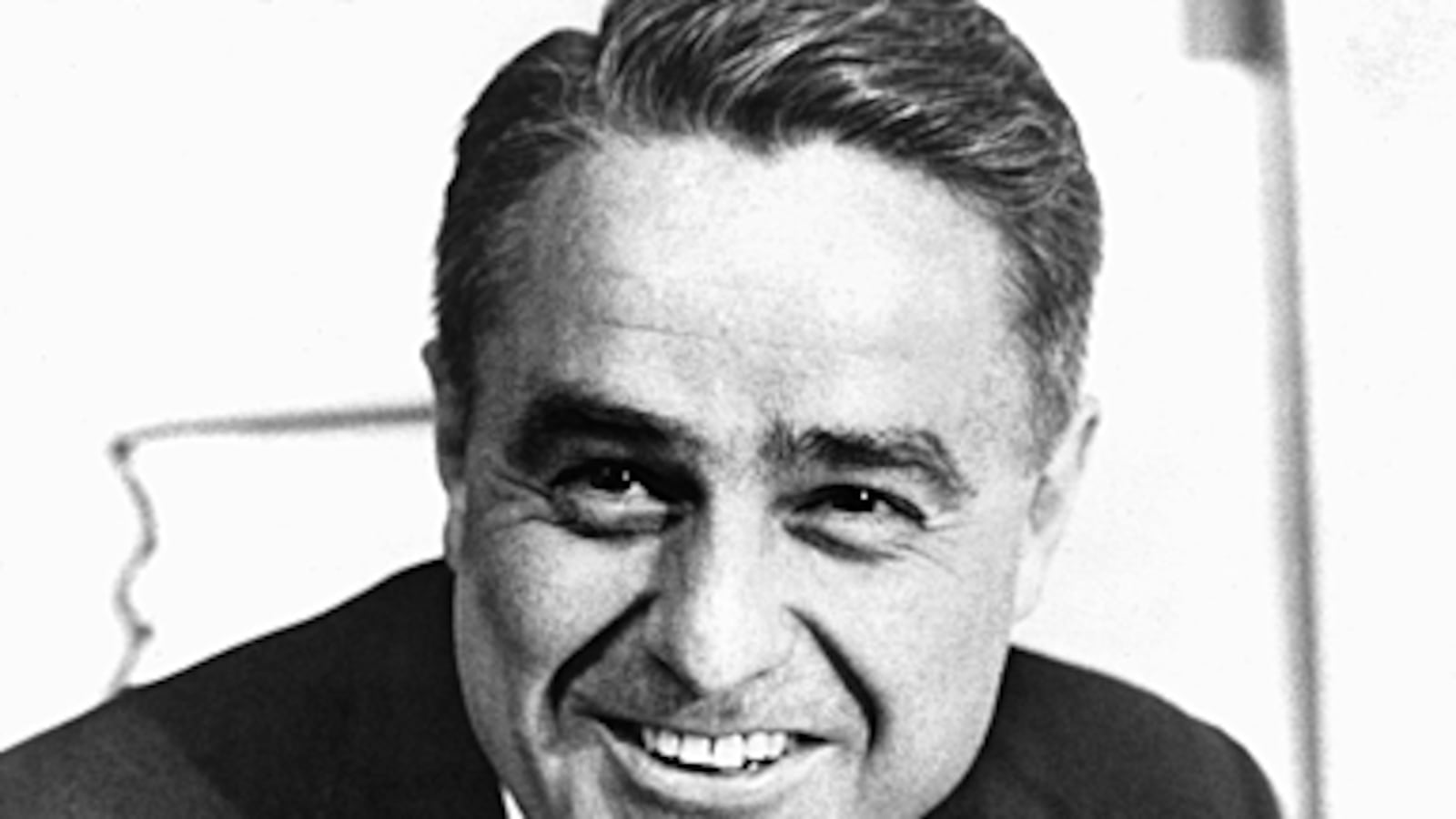

Photos: Sargent Shriver

Shriver's passing at the age of 95 comes as Kennedys, associates and admirers gather in Washington to celebrate the 50th anniversary of that exciting, hopeful moment, and leads them to reflect on something more than John Fitzgerald Kennedy, his accomplishments and his thwarted promise.

When they talk of Sarge, they recall his work in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, but dwell on his personality, his constant enthusiasm, the faith that made him a daily communicant at Mass, his commitment to social justice and his love for his wife, Eunice Kennedy Shriver.

Even before he came to Washington in 1961, Shriver had been a leader in his own right. He moved to Chicago to manage Joseph P. Kennedy's Merchandise Mart. Christopher Kennedy, Shriver's nephew and now the head of the Mart, recalls being told how important it was for the Mart to be a showplace for American innovation in industry. But he was a civic leader, too, president of the Chicago Board of Education and head of the city's Catholic Inter-Racial Council, pressing to desegregate the public and parochial schools before his in-laws ever focused on civil rights.

"He had enthusiasm to the hilt," said his niece, Kathleen Kennedy Townsend. "That's really who he was, with a real vision of service and making a difference and he had that enthusiasm, all the time I have ever known him, even with his Alzheimer's, he was enthusiastic."

As the first head of the Peace Corps, he joked that he had been chosen because he would be easy to fire if things worked out badly. But he plainly loved the work. In 1964 he called it "the best job in Washington" because of the dedication of volunteers—"a committed generation of Americans who really care about the human condition and are dedicated to the quest for progress for all mankind."

Charles Peters, who functioned as an in-house inspector for the Peace Corps then, said Shriver succeeded in communicating his own "glorious, infectious enthusiasm" to volunteers, who needed the boost because in the early days it took courage to volunteer and assignments didn't always work out well. Lyndon Johnson thought him such a success that he insisted in 1964 that he add to his Peace Corps duties with another, harder job. Johnson got him to run the War on Poverty, even though Shriver had little experience with the subject in America. His optimism led him to compare ending poverty to eradicating scarlet fever and diphtheria. He predicted that in a few years, perhaps less than a decade "the number of people mired permanently in poverty will be almost eliminated in America."

"He had enthusiasm to the hilt," said his niece, Kathleen Kennedy Townsend. "That's really who he was, with a real vision of service and making a difference."

That hasn't happened of course, and in later years Shriver would say that war had not been lost; it had just not been fought hard enough, with enough money, to win. But the remains of the War on Poverty still help poor Americans through Head Start, the Job Corps, and the Legal Services Corporation, among others.

Shriver gained prominence from his association with his in-laws, but that did not bring political success. In 1972, he was George McGovern’s eventual choice to replace Thomas Eagleton as the vice presidential candidate on the Democratic ticket. In fact, McGovern said this week, he probably would have chosen instead of the ill-starred Eagleton at the Miami Beach convention, but Shriver was traveling in Russia and could not be reached by phone to be offered the nomination. Once he was the belated nominee, McGovern said, Shriver “never lost that enthusiastic, optimistic attitude” even though the campaign by then was 20 points behind Nixon and Agnew.

His earnest effort that year can be explained by a story Tip O'Neill liked to tell. Tip recalled suggesting to Shriver that the route to popularity in a South Boston bar was to buy a round. Shriver took his advice, but when the bartender finished taking orders for beer or "beer and a shot," he asked what the candidate would have. As Tip told it, shaking his head, the reply was "Courvoisier with a twist." His own 1976 campaign for the presidency, focused clearly on his brother-in-law's legacy, went nowhere.

Bob Shrum, the Democratic consultant and a longtime friend, tells a more upbeat story. One afternoon he and Shriver arrived at the Shriver home as Eunice was running a Special Olympics event. She had put out a wine punch for the athletes' parents. Sarge sampled it and asked what wine was used. A servant said Eunice had told them to just take anything handy. They had opened a case of Chateau Lafitte Rothschild '48, a gift from Giscard d'Estaing, president of France when Shriver served as ambassador. Shrum reports that Shriver was momentarily nonplussed, but then smiled and said, "Then we'd better drink a lot of it."

That is just one of the stories friends tell about Shriver and family. Mark Shields, who worked on that 1972 campaign, said, "I've never known any candidate with a better relationship with his children and his family than he did."

Vicki Kennedy said Eunice and Sarge "raised remarkable children. Every one of them is involved in giving back. Every one of them is an achiever. Every one of them learned by the example of their parents."

And Townsend said their 56 years of marriage "was really one of the first great partnerships. He was absolutely successful, as we know, first head of the Peace Corps, head of the poverty program. But he just was enchanted by Eunice. He loved her. He loved everything about her. He appreciated her, and he supported her work."

After Eunice died and the family assembled in Hyannisport, she said, "Sarge put his arm on her coffin and said 'We did it, Euni, We did it. We fought the good fight. We fought for America. We did it. I love you Euni, I love you.' "

Adam Clymer is a former chief Washington correspondent of The New York Times and author of Edward M. Kennedy: A Biography.