At the end of Wednesday night’s season five premiere of Schitt’s Creek, the crows rise.

Catherine O’Hara’s fallen soap opera star Moira Rose thinks she’s landed her comeback vehicle: The Crows Have Eyes III: The Crowening, an “apocalyptic fantasy about mutant crows” directed by a hot young director named Blaire, no last name, who is only there for the paycheck. “I think we all know what we’re making here,” he says. “A timely allegory about prejudice,” she answers earnestly, not skipping a beat.

Moira throws herself into the role. She becomes Dr. Clara Mandrake, a half-human, half-crow figurehead to the mutant-crow community. Dressed in a lab coat adorned with a ratty plumage of black feathers and campy black makeup fashioning a beak, O’Hara-as-Moira takes her perch in a human-sized crow’s nest and caws her way through a rousing monologue that mobilizes the crows, flapping her arms like wings so maniacally it’s a wonder the actress didn’t actually take flight.

It is one of the funniest things I’ve ever seen.

As luck would have it, we’re sitting with the person who dreamed it all up.

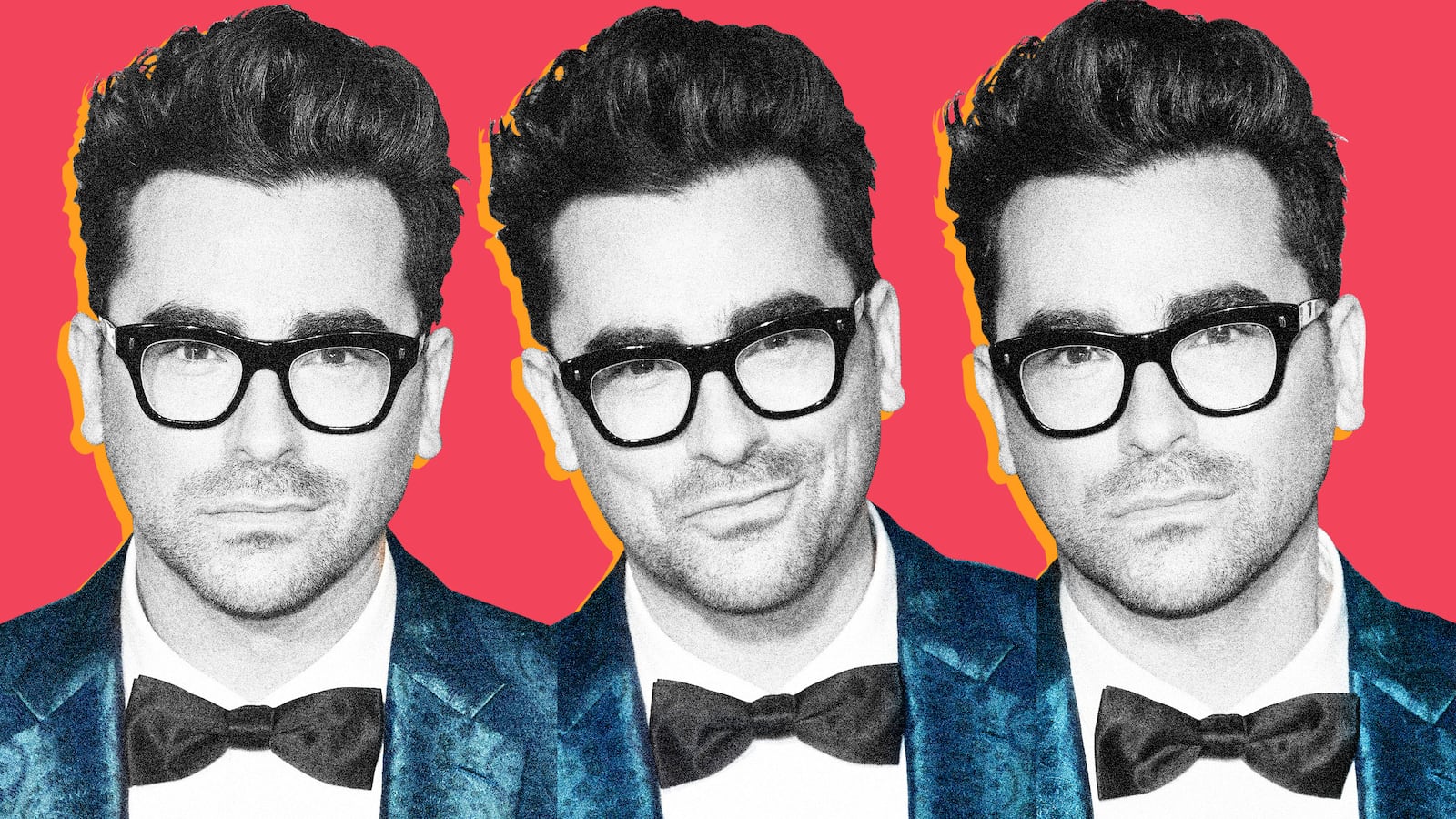

“A Christmas delight!” Dan Levy coos as red and green juices are placed on our table. The co-creator, writer, and star of Schitt’s Creek is half-heartedly pledging healthfulness in order to survive a busy press blitz in support of the show.

In a bit of a thrill, his lips purse in that way familiar to anyone who has seen his sitcom: a sort of pucker curled to the side and a glint of mischief twinkling from his eye, like he’s keeping a secret, or about to tell you something naughty, or bashfully pleased with himself, or maybe all three.

Then a third beverage is brought to him. “Wow…” He starts laughing and pitches his voice an octave higher, mocking how we might relay the situation in our article in a dramatic cadence that his character, David Rose, might use. “‘He sat down to 52 juices…’”

Assured of proper hydration, we return to the business at hand: Catherine O’Hara, the Hope Diamond of the comedy world, leading a mutant crow uprising.

“I can’t say when we were breaking that story that we didn’t think, ‘I wonder if we should run this by Catherine first…’” he says. “We didn’t. Fortunately, she was game for it. The look was all her own. The voice was her idea. So I wish I could take credit for all of that. We just wrote it and she ran with it.”

Levy has been very Canadian about the show’s surging success, passing off credit to his genius co-stars, Netflix, the marketing muscle of Pop TV. But the sheer volume of all the love, especially in the last weeks and months, is starting to wear this exquisitely coiffed maple leaf’s armor of humility down.

Much of the show’s run thus far has been defined by wails of “underappreciated!” from its fervent fans, a vocal group beguiled by the show’s wholesome peculiarity and punchy cocktail of tart zingers washed down with a tonic of unabashed warmth and love. That narrative, we can indisputably report, has expired.

At this moment in time, sitting at a café near Rockefeller Center where polite patrons stop to compliment him, Levy is in a wholly unexpected and surprising position. He is the most popular man in TV.

How Schitt Happened

For the uninitiated—and that’s a dwindling bunch—Schitt’s Creek was created by Levy and his father, Eugene, the comedy legend known for starring with O’Hara in a slew of Christopher Guest movies. It centers on the Rose family, wealthy socialites whose lives are upended when they are stripped of their fortune and lifestyle, forced to live in a motel together in a town they once purchased as a joke. A co-production of Canada’s CBC and the then-fledgling U.S. Pop network, it premiered modestly in 2015.

Things exploded once Netflix began hosting episodes in 2017. As audiences binged the library of its first three seasons, a fourth began airing on Pop that made noise for staging swoon-inducing romantic scenes between Levy’s David and his boyfriend, with outlets covering the show’s refreshing queer representation. The zany humor and performances from its core cast—the Levys, O’Hara, and Annie Murphy as Alexis Rose—was matched by a palpable emotionality. When season four debuted on Netflix months later, Schitt’s Creek’s popularity skyrocketed.

“It’s been a happy coincidence,” Levy says. The Netflix deal, the growing word of mouth, and the emotional subject matter of the fourth season all organically collided at the exact right time.

The series popped up on dozens of critics’ best of 2018 lists at the end of year. (The Daily Beast ranked it ninth.) Last weekend, Levy was a proud papa beaming in a shimmering blue tuxedo as the show celebrated its first-ever Best Comedy Series nomination at the Critics’ Choice Awards. They were beside the Sharp Objects table and the Killing Eve table. “We were In! The! Mix!” Levy cheers.

In recent weeks, the cast—Levy especially—has been omnipresent in TV and magazine profiles. The Advocate talked with him about queer relationships. New York magazine went shopping with him. Al Roker and Dylan Dreyer joked with the cast about not being able to say the show’s title out loud on the Today show without fear of fines.

Deeply felt, passionate love letters to the series appeared in Vanity Fair, Washington Post, Variety, and more. “It’s wonderful but it’s also in a way completely destabilizing because I’m thinking, we’ve been doing this for a very long time,” Levy says. “What’s going on?”

He found himself struggling over whether to continue sharing kind articles on social media out of fear that it might seem obnoxious, but ruled in the last week that there’s no need to overanalyze his enthusiasm for the success the series is having.

“I am so proud of the 147 people who work on the show and I will continue to promote hopefully without sounding arrogant or that I am reveling in the experience too much,” he says. “There will come a point where I don’t have the show. To look back on this experience and some of the wonderful things that have been written and feel like I didn’t share them or really embrace that because I was scared what people would think is really lame.”

That’s how he found himself weeping on a street corner outside the World Trade Center on a Tuesday afternoon.

The New York Times had just published a glowing review of the new season that hit on everything Levy had worked so hard to be sure the show represents. He got through two-thirds of the piece before totally losing it on the sidewalk.

“I think I had been pushing away a lot of that for a long time to sort of protect myself from it, and that really cracked it open.” He takes a pause. His shoulders start to shake while he tries to stifle one of those silent giggles that take over your entire body. He shakes his head: “And then I cried again in the next interview.”

He had also just received an email from a woman about her experience with her son coming out of the closet. She wrote that she was never unsupportive of her son being gay, but was fearful for what his life would be like as a gay man. Watching Schitt’s Creek made her feel like he was going to be fine.

“It just made me just completely fall apart in front of this young woman,” he says. “She was like, ‘Um, is everything OK?’”

These are unusually high emotions wafting from a show with a running joke about Catherine O’Hara wearing different wigs. The remarkable thing about the series at this point in its run is that all of its main characters are depicted in happy, healthy, intensely loving relationships. That said, it’s the romance between Levy’s David and Noah Reid’s Patrick that gets the most attention.

The way Levy has written David’s sexuality has always made news. The line, “I like the wine and not the label,” used to explain that he was pansexual has become so popular—Levy once repeated a version of it to Larry King—that it’s on tote bags and T-shirts.

But then Patrick serenaded David at an open mic night.

Simply the best

Levy always knew that he wanted to write something incorporating Tina Turner’s “The Best.” He couldn’t imagine the cultural moment it would become.

He scripted a scene in which Patrick reveals his true feelings to David by singing an acoustic version of the song at an open mic night, the kind of grand gesture that David would ordinarily have cringed at were it not so rooted in genuine emotion. Reid actually crafted the stripped-down arrangement of the song himself. A few weeks before the shoot, and nervous that Reid had forgotten his assignment, Levy texted him for an update. He sent back an MP3 recorded in his living room. It was the middle of the night, and Levy was in bed when he first listened to it. He began sobbing.

“I cried then, and I cried when we shot it, and I cry when I watch it,” he says. He tells me that the set was so emotional that day that they had to shoot around O’Hara because she was crying so hard.

It’s the kind of honest, romantic, pure expression of love that is never shown on TV between two men, not in that grand of a fashion. It transcended. Fans, gay fans especially, cherish the scene deeply. It’s often cued up in repeat viewings as some sort of TV comfort food, or when they need a good cry.

A bookend scene at the end of the season in which David dances for Patrick to the same song proved just as emotional, which surprised Levy. He talks about downing half a bottle of Prosecco before shooting and finding himself prone on the ground, exhausted from dancing when the director called cut, confused that he couldn’t hear any laughter on set from what was supposed to be a hilarious scene. The director was weeping. “I don’t think I expected it to resonate as deeply with people as it has,” he says.

There are purposeful decisions that Levy has made when it comes to how David and Patrick’s relationship would be depicted. They would kiss as often as real couples kiss, even though they are two men and that’s not normally shown on TV. Homophobia, or any judgment about sexuality in general, wouldn’t exist.

The result has been spectacular. LGBTQ fans of the show are reconsidering the kind of love story they deserve and deserve to display to the world, something that Levy says has affected his own life. And at a time when nearly everything in culture is polarizing and met with outrage, his storyline about a pansexual former socialite and his loving boyfriend has been met with nothing but warmth and joy.

“What we’re doing isn’t combative in terms of shaming people for their beliefs,” he says, attempting to analyze that accomplishment. “All we’re doing is putting something out in the world as it should be, according to me. I think in presenting something so casually, we have really allowed people the space to learn and not feel like they’re being pinned against the wall with a person’s agenda.”

The world Levy creates on Schitt’s Creek, in which love really is love, meanness is fleeting, and judgment isn’t a concept, is not so far from reality to be utopian. It doesn’t seem unattainable or out of reach, which is why it resonates with people.

In a recent interview with Out, Levy revealed that he has no plans to alter that, suggesting that David and Patrick will be together for a good long while. And as for how he sees the show progressing, in general, he tells me that he knows how it ends. After shooting season five, he’s confident in there being more story to tell on the way there, too. He estimates that the narrative is “halfway across the football field.”

“You never want someone who has stuck with your show for four seasons to suddenly feel taken advantage of because you’ve decided to cash in and make 400 more episodes when you really should make six.”

So take comfort, then. Season five, he says, is “simply the best” one yet.