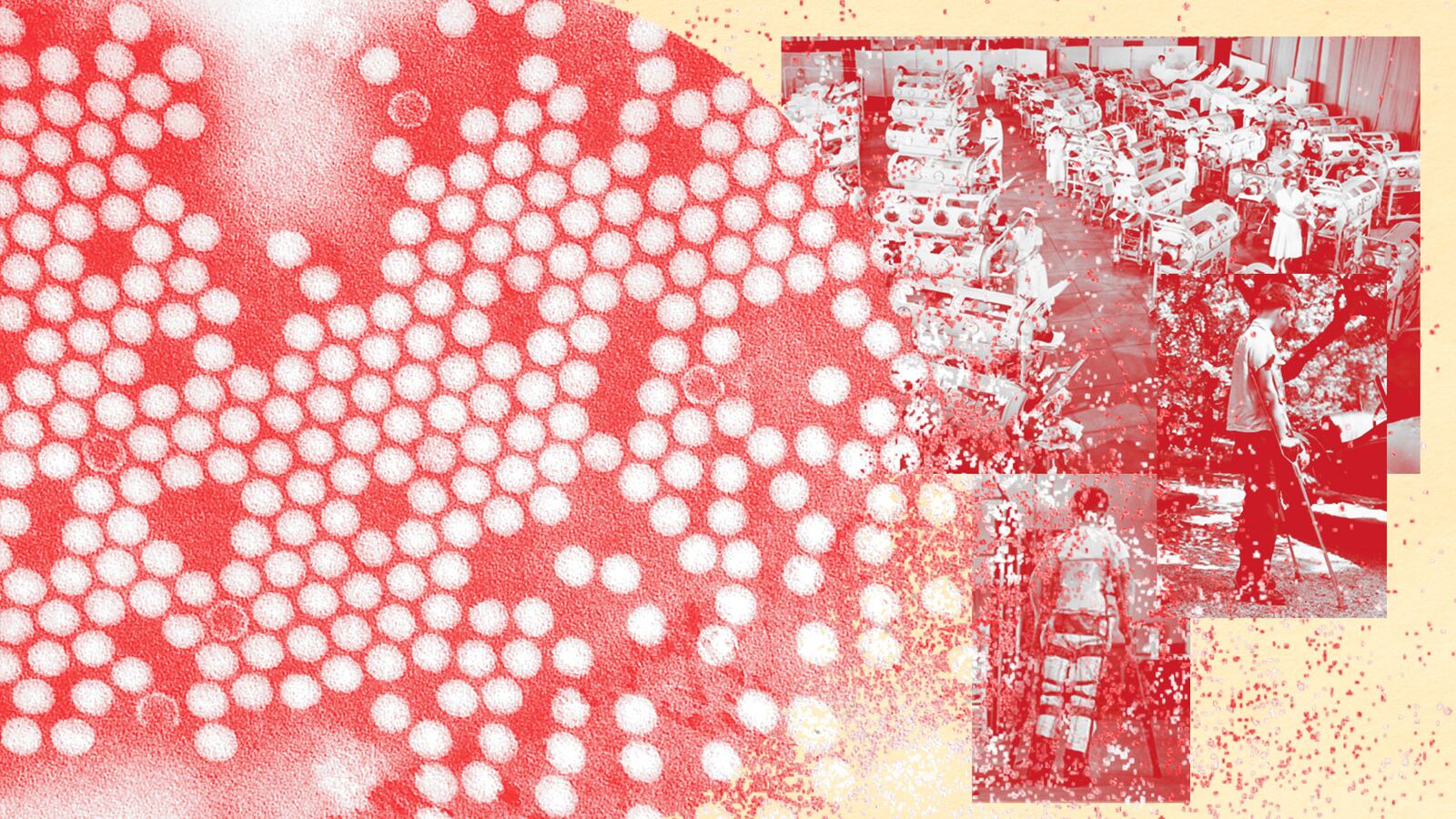

Polio has reappeared in the United States for the first time in a generation. On July 18, the New York State Department of Health told the U.S. Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention it had detected the poliovirus, which can cause paralysis or death in a small percentage of cases, in a young adult from Rockland County outside New York City.

New York authorities subsequently detected the virus in sewage in Rockland and neighboring Orange County—evidence of transmission in the local community.

That first case prompted authorities in the U.K. and Israel to increase their surveillance—they found polio too.

A polio crisis could be brewing. But despite describing polio as “one of the most feared diseases in the U.S.,” the CDC is trying to maintain total government control over testing for the poliovirus. Only the feds and certain states that already do polio testing would be equipped to monitor for the pathogen.

In withholding the testing materials and protocols, private labs—such as Massachusetts-based surveillance startup BioBot—would need to detect and track the virus, the CDC risks allowing the virus to spread unnoticed in some communities, while also limiting study of a potential outbreak.

“They want to do it themselves,” Vincent Racaniello, a professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at Columbia University, told The Daily Beast. “Just as they wanted to control the COVID tests at the beginning of the pandemic.”

The thing is, even the CDC admits that it botched the initial response to COVID. Last week Rochelle Walensky, the CDC director, told the agency’s 11,000 employees that the CDC needed a top-to-bottom overhaul. “To be frank, we are responsible for some pretty dramatic, pretty public mistakes, from testing to data to communications,” Walensky said.

The CDC might be about to repeat some of its mistakes. Amy Kirby, an Emory University epidemiologist who heads the CDC’s National Wastewater Surveillance System, did not respond to a request for comment.

The poliovirus spreads through direct contact with fecal matter. Before the invention of an oral vaccine in the early 1950s and a sweeping campaign of childhood vaccinations, polio outbreaks caused more than 15,000 cases of paralysis in the U.S. alone every year.

Vaccines squashed polio. By the 1970s, the disease had virtually disappeared from all but a handful of the poorest and most remote countries, such as Afghanistan. When it reappeared, it was usually as a result of international travel—and local health authorities quickly isolated the infected and halted further spread.

The CDC tracked the poliovirus in a U.S. community just once between 1979 and 2022. In 2005, the Minnesota Department of Health identified poliovirus in an unvaccinated infant girl in a largely unvaccinated Amish community. Three other kids got sick before the virus was contained.

Today 90 percent or more of people in the richest countries, including the U.S., are vaccinated against polio. But childhood vaccination rates have been slipping as anti-vax attitudes take hold in a growing minority of people. It’s no accident that Rockland County, where the CDC detected the poliovirus last month, has a lower vaccination rate than the rest of the country: around 60 percent.

“The occurrence of this case, combined with the identification of poliovirus in wastewater in neighboring Orange County, underscores the importance of maintaining high vaccination coverage to prevent paralytic polio in persons of all ages,” the CDC stressed in a report it posted last week.

The public-health stakes couldn’t be higher as the world copes not only with the ongoing COVID pandemic, but also with an accelerating outbreak of monkeypox. But potential looming disaster hasn’t motivated the CDC to release to private labs the DNA primers they would need to detect polio. “Essentially no one is allowed to do it except public [i.e. government] health labs,” Rob Knight, the head of a genetic-computation lab at the University of California, San Diego, told The Daily Beast.

Without the primers and other materials, private labs—and researchers associated with those labs—can’t help the government find polio in other communities. Racaniello compared the CDC’s reluctance to widen polio testing to the agency’s equally tight control of COVID testing during the early months of the novel-coronavirus pandemic. “Which did not work out well,” Racaniello noted in a tweet.

The worst-case scenario is that polio spreads for weeks without anyone realizing it—much in the way monkeypox spread unnoticed at first, as many doctors mistook it for herpes or some other sexually transmitted disease.

The CDC’s recalcitrance appears to be bureaucratic. From a technical standpoint, detecting the poliovirus in sewage isn’t any harder than detecting SARS-CoV-2 or any other virus, Knight explained. Take a sample from sewage, run a PCR test.

But in the U.S., the regulations regarding polio are stricter than for other diseases. “From a regulatory standpoint, you have to account for every single sample that might contain polio,” Knight said. Polio surveillance, he added, is a “paperwork nightmare to get set up.”

There’s also the cost factor. Ramping up polio testing at private labs could cost millions of dollars. And the labs might want the government’s help paying for it. CDC leaders may have noted the growing reluctance of the U.S. Congress to pay for COVID testing and concluded that it’s just easier for the CDC to keep polio testing in-house.

But easier doesn’t necessarily mean better, not when public health is concerned. With some effort and a little money, private labs could reinforce the government’s surveillance system. “[It] should not be hard to do wastewater testing,” James Lawler, an infectious disease expert at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, told The Daily Beast. “BioBot and others who are doing surveillance already could stand up quickly.”

Speed and comprehensive surveillance both matter when it comes to infectious diseases. A little effort on the part of the CDC, and some government funding, could make the difference between a once-in-generation polio outbreak that stalls out in a pair of smallish New York counties, or a much wider outbreak potentially affecting the entire U.S.

Or even the whole world.