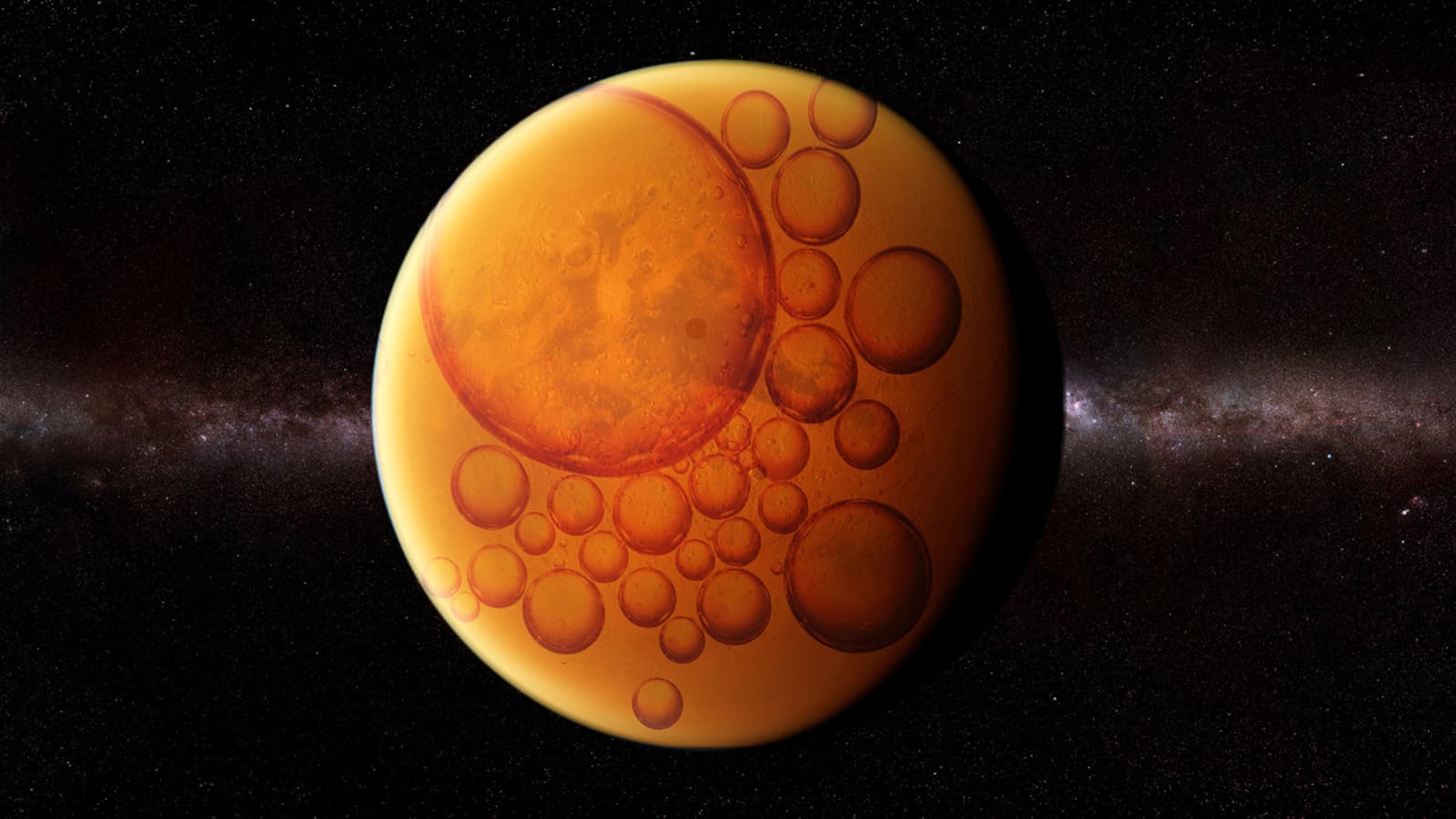

A pair of American and German astrobiologists has found oil on Mars. And where there’s oil, there’s usually life.

Technically speaking, Dirk Schulze‑Makuch and Jacob Heinz didn’t find oil. Rather, they found organic compounds called “thiophenes” that are also present in crude oil, coal, and truffles.

Thiophene molecules include four carbon atoms and a sulfur atom in a ring-like shape. There are lots of ways thiophenes get created. Not all of them are “biotic,” meaning they involve life.

But many of them are biotic. And if that’s the case with the thiophenes Schulze‑Makuch and Heinz found on Mars, then the discovery could be proof of, well, alien life.

“If they are biotic, it means that there was early life on Mars,” Schulze‑Makuch told The Daily Beast, “and that there is possibly still extant life in some ecological niches of Mars today.”

The thiophenes turned up in dried-up mud that NASA’s Curiosity Rover dug up in Mars’ Gale Crater. Curiosity landed on the Red Planet in 2012 and has spent the last eight years rolling around Mars, periodically pausing to scoop up samples, analyze them, and beam the raw data back to Earth.

Schulze‑Makuch from Washington State University and Heinz from Berlin’s Technische Universität studied the numbers from Curiosity and concluded the Martian dirt held thiophenes. They published their findings this month in the science journal Astrobiology.

The astrobiologists can’t say for sure what produced the Martian thiophenes. On Earth, thiophenes often result from the eons-long process of fossilization: plankton living, dying, sinking to the seafloor, getting buried and pressure-cooked into oil.

But thiophenes can also result from a non-organic process called thermochemical sulfate reduction, which involves heating up certain compounds to hundreds of degrees Fahrenheit. A meteorite impact could spark thermochemical sulfate reduction.

The best Schulze‑Makuch and Heinz could do was identify all the ways the thiophenes might have gotten into the Martian dirt.

“We identified several biological pathways for thiophenes that seem more likely than chemical ones, but we still need proof,” Schulze‑Makuch said in a statement. “If you find thiophenes on Earth, then you would think they are biological, but on Mars, of course, the bar to prove that has to be quite a bit higher.”

To prove that the Martian compounds came from some kind of alien life, Schulze‑Makuch and Heinz would have to find the parent molecule. In other words, tiny fragments of the Martian equivalent of Earth’s plankton tissues that, over millions of years, eventually became oil.

Just don’t count on Curiosity to do the heavy lifting. The decade-old rover doesn’t have the equipment to handle really delicate samples. Curiosity gathers a lot of its data by way of pyrolysis gas chromatography—in essence, it burns up samples and analyzes the resulting gas.

The extreme heat the process requires can wreck the very thing it’s examining. The sample in which Schulze‑Makuch and Heinz found their thiophenes reportedly was a bit damaged.

A better rover is coming. In 2022, the European Space Agency plans to launch its Rosalind Franklin probe. Named for an English chemist who helped define the molecular structure of DNA, Rosalind Franklin is a decade newer than Curiosity and boasts better instruments.

“If we want to find life on a planetary body, we have to get close and personal,” Schulze‑Makuch said. Rosalind Franklin is the way.

Of course, there’s no guarantee the ESA probe will make it all the way to Mars and safely deploy on the Red Planet’s dusty surface. “The next critical step is whether ESA manages to land their rover,” Schulze‑Makuch said.

But the astrobiologist said he’s optimistic. “With the instrumentation that the space agencies can put on the landers and rovers nowadays, we can look for organic compounds rather than just water, which is much more revealing.”

And he said he shares the increasingly popular notion in science circles that Earth’s space agencies are closing in on firm proof of alien life. A team at Harvard recently found proteins on a meteorite, possibly proving that life can evolve in the cold of space.

Meanwhile NASA’s InSight probe found evidence of seismic activity under Mars’ surface, which could point to ongoing volcanism on the Red Planet. Volcanoes can kick-start the evolutionary process.

NASA’s sending a probe to Jupiter’s moon Europa, which might contain a subsurface ocean capable of supporting life. The agency’s also eyeing Enceladus, a moon of Saturn that has its own saltwater ocean.

“And there are a lot more other exciting missions in the planning,” Schulze‑Makuch said. Maybe his and Heinz’s thiophenes turn out to be abiotic rather than biotic, meaning they resulted from, say, a meteorite impact. Maybe they’re not evidence of alien life.

But that doesn’t mean the evidence isn’t out there, just slightly beyond our ever-widening grasp.