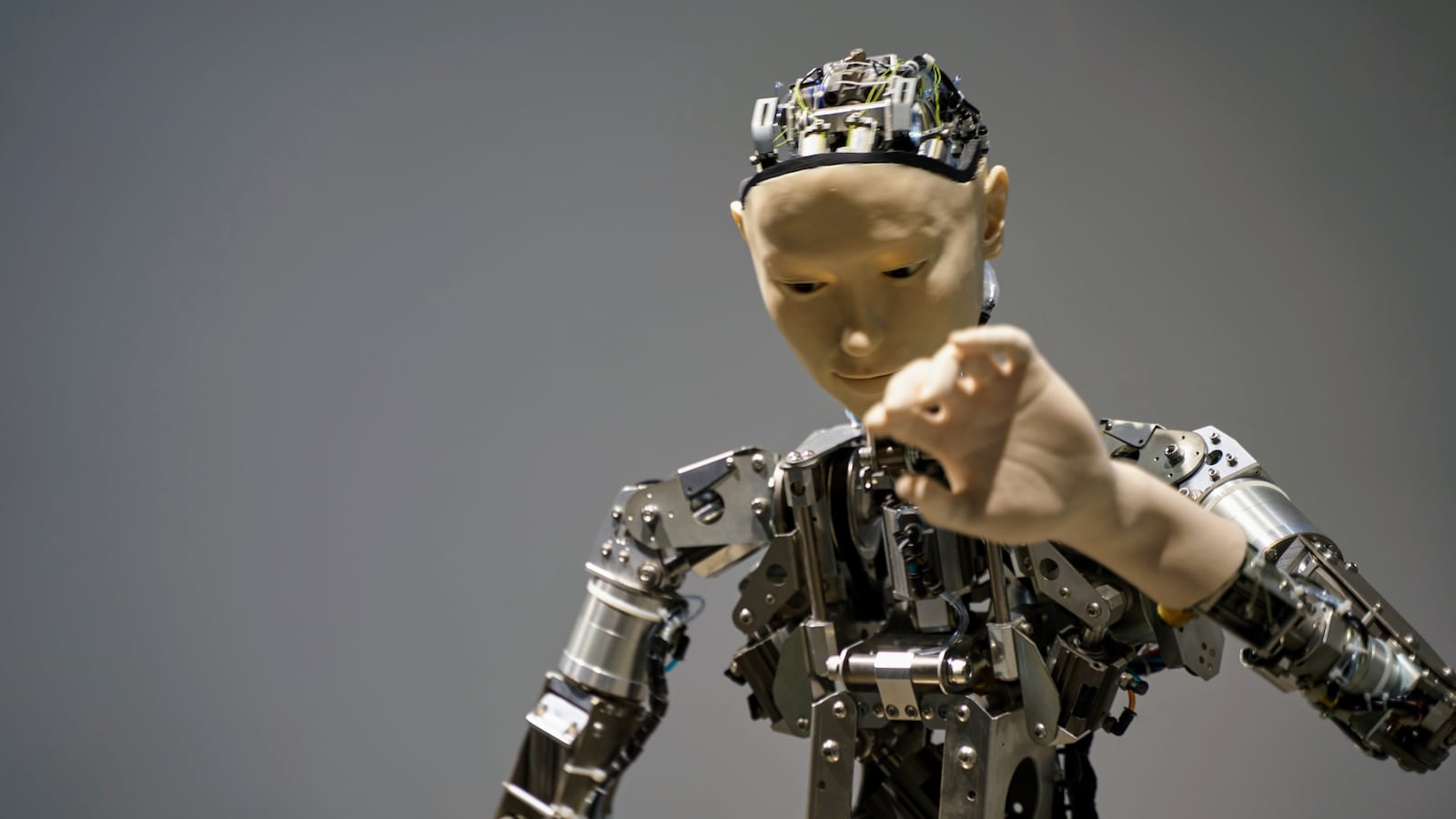

In the 1970s, Masahiro Mori, then a robotics professor at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, made an unsettling hypothesis: The more lifelike a robot became, the more creepy humans would find it. This theory of the “uncanny valley” hasn’t stopped scientists from making humanoid robots (like Sophia, who at one point claimed she wanted to destroy humanity) or endowing these hunks of metal with useful but terrifyingly powerful hands.

If that wasn’t enough, scientists have now blessed robots with a human-like sense of touch to help them grip better. In a new study published Tuesday in the Journal of The Royal Society Interface, researchers in the U.K. took an artificial robotic fingertip and dressed it up in 3D printed skin capable of tactile sensing and relaying electric signals much like human skin. Called the TacTip, this new advancement may create a generation of dexterous robots and even help improve prosthetics to resemble their flesh-and-blood counterparts.

“Many different technologies are being explored for tactile skin in robotics,” Nathan Lepora, a robotics engineer at the University of Bristol who led the study, told The Daily Beast in an email. “The TacTip is special because its design is based on the mechanical structures of human skin.”

A robotic hand with the new 3D printed tactile skin attached to the fingertips.

Nathan LeporaHuman skin is filled with embedded structures called papillae, which are rife with receptors that sense pain, temperature, pressure, or the stretch of the skin itself. These receptors help tell our brains how to pick up or handle objects.

While Lepora and his team didn’t recreate all receptors found in human skin, they mimicked one type called mechanoreceptors, which are the primary tactile sensors found near the skin’s surface. The synthetic skin has a stiff upper layer similar to the epidermis (the outermost layer of skin on the human body) followed by a softer layer studded with papillae-like structures. Inside each of the papillae, the researchers placed tiny cameras to image the movement of the papillae as they’re pushed by a surface. These images are then processed as a signal on a computer.

What really thrilled Lepora and his team was the fact that the 3D printed skin produced signal activity on par with real human skin.

Cross-section of the 3D printed tactile skin.

Nathan Lepora“When we compared these artificial receptor signals with real measurements physiologists have taken, we found a very close match,” said Lepora. “This is the first time that signals from an artificial fingertip have been directly compared with recorded neural activity.”

This new development is promising on two counts. First, it means engineers are closer to developing robotic limbs imbued with receptors that can sense the environment similar to the ones in the human body. And second, it could help us design prosthetics that restore a sense of touch for amputees, a challenge biomedical engineers have spent a long time trying to tackle.

The sensitivity of the creepy new robot fingertips is still limited (possible due to the skin being thicker than real skin). Lepora and his team are working on slimming down their synthetic epidermis to a quality and functionality just as good, or even better, than human skin. It can’t get more uncanny valley than that.