Remember those undead pig brains from the Before Times? In 2019, a team of Yale School of Medicine researchers gave us all nightmare fodder when they restored some electrical function and cellular activity to pig brains that were decapitated and had been sitting at room temperature for four hours.

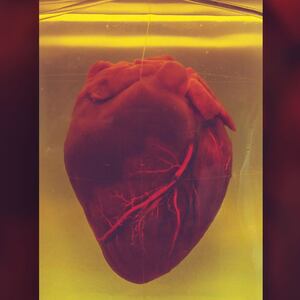

Now, the same group of researchers has applied its experimental treatment to the whole hog. By modifying their treatment for the entire body, not just the brain, the researchers were able to partially revive the organ systems of pigs after they had been dead for an hour. The team hopes its treatment, called OrganEx and detailed in a new study published Wednesday in Nature, will reshape scientific thought around death and expand the conditions under which life-saving transplants can be performed.

“The technology has a great deal of promise for our ability to preserve organs after they're removed from a donor,” study co-author Stephen Latham, a bioethicist at Yale, told reporters earlier this week. By hooking up a deceased person’s organ to this treatment prior to transplant, doctors could one day “be able to transport it a long distance over a long period of time to get it to a recipient who needs it.”

Much further down the line, Latham added, OrganEx could be used to bring people back to life whose hearts stop as a result of drowning or experiencing a heart attack.

This is only the latest in a rapid string of medical breakthroughs in the last year involving pigs. Last month, scientists reported successfully transplanting working pig hearts into medically deceased humans and keeping the organs functioning for three days. In January, another group pulled off the same feat in a brain-dead man using pig kidneys.

But this latest milestone goes a step further, in some unexpected ways. “The latest findings raise a slew of questions—not least, whether medical and biological determinations of death will need revising,” wrote Brendan Parent, a transplant ethics and policy researcher at NYU Grossman School of Medicine who was not involved in the research, in an accompanying essay in Nature.

When human cells go without oxygen, they die. Modern medical techniques that attempt to bring these cells back from the brink are imperfect—in other words, there is a point of no return beyond which cells, organs, and people die.

OrganEx combines two technologies to defy inevitable death: a device that mimics the effects of the heart and lungs by pumping oxygen-laden blood through the body, and a series of chemical solutions that are also circulated. These solutions include drugs, the blood thinner Heparin, and a special mixture that balances out electrolytes. In the study, the researchers compared their treatment to an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation system (ECMO), the standard treatment used in hospitals to substitute the function of a patient’s heart and lungs.

OrganEx trounced ECMO across the board. OrganEx-treated pig cells showed more signs of repair after being left without oxygen for an hour; meanwhile, ECMO-treated pig organs did not all receive enough oxygen, and many of the pigs’ small blood vessels had collapsed after six hours of treatment.

Importantly, these results do not indicate that OrganEx restored life to either the pigs or their organs, Latham said. In fact, the researchers purposely designed their experiments to inhibit any coordinated electrical activity in the brain that could lead to consciousness or the sense of pain.

The dead pigs that were treated with OrganEx exhibited one more startling difference, too. When researchers injected the OrganEx pigs with a contrast dye for a type of X-ray, the dead animals moved their heads, necks, and torsos “across multiple joints and muscle units,” according to the study. Neither the ECMO-treated swine nor a group of alive but heavily sedated pigs moved, raising even more questions that the researchers could not answer.

“We can say that animals were not conscious during these moments,” senior author and Yale School of Medicine neuroscientist Nenad Sestan told reporters. “We don't have enough information to speculate why they moved—it does implicate preservation of some motor functions,” but more research will need to be conducted to understand the eerie reaction.

“There's nothing about this motion that in any way implicates any kind of brain activity,” Latham added, comparing it to a reflex a person might trigger by touching a hot surface. “I do think it was quite startling to the people who were in the room, because pigs are strong and it’s a powerful movement of the head and neck of the pig.”

Wow, a new nightmare unlocked that is somehow even more terrifying than measuring electrical activity in decapitated pig heads. Thanks, science.