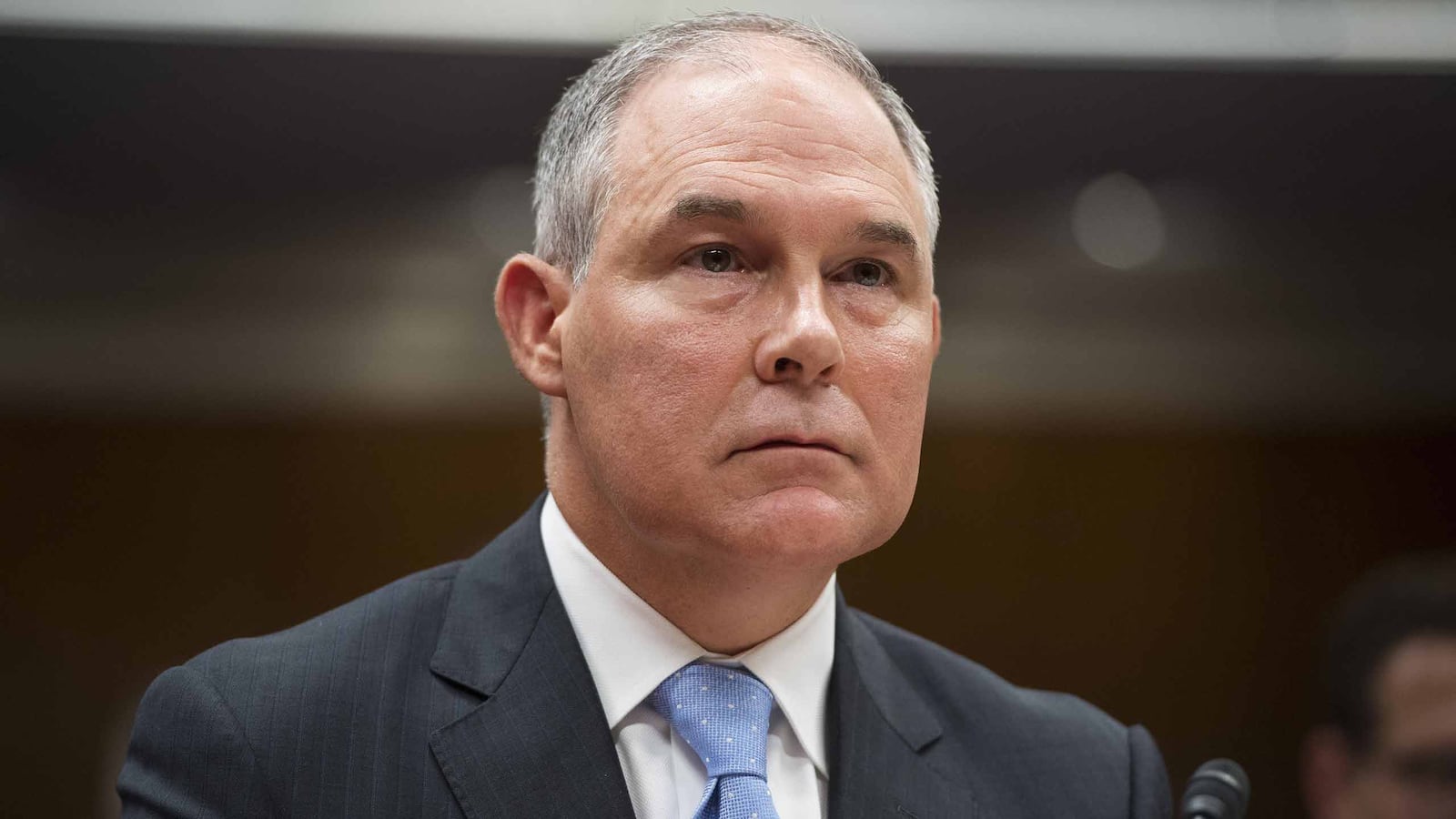

As he doggedly tries to save his job amid a mounting ethics scandal, Environmental Protection Agency chief Scott Pruitt has insisted that there was no formal or informal conflict of interest when he rented a room from high-profile Washington D.C lobbyist, J. Steven Hart.

“Mr. Hart,” Pruitt claimed in an recent interview with Fox News on Wednesday, “has no clients who have business before this agency.”

A review of lobbying disclosure forms and publicly-listed EPA records, however, suggests that Pruitt is either lying or is woefully unfamiliar with the operations of his own agency.

Far from being removed from any EPA-related interests, Hart was personally representing a natural gas company, an airline giant, and a major manufacturer that had business before the agency at the time he was also renting out a room to Pruitt. One of his clients is currently battling the EPA in court over an order to pay more than $100 million in environmental cleanup costs.

The New York Times previously reported that Hart’s firm, Williams & Jensen, represented a company that got a pipeline expansion project approved by the EPA. But that only scratches the surface of Hart’s deep involvement in the energy industry—and advocacy on behalf of clients with business before the agency that his one-time tenant leads.

Hart himself was part of a team of four Williams & Jensen lobbyists that has reported lobbying Pruitt’s EPA. They did so on behalf of Owens-Illinois, a glass bottle manufacturer that paid $39 million in 2012 to settle EPA allegations of widespread Clean Air Act violations by a subsidiary. In June 2017, while Pruitt lived at Hart’s DC condo, another of the company’s subsidiaries settled additional EPA allegations that it violated the same law.

“We know that Steven Hart’s firm had clients before the EPA,” said Craig Holman, Government Affairs Lobbyist for the good-government group Public Citizen. “So his insistence that there is no conflict of interest is just off the wall.”

Even clients of Hart’s who didn’t enlist him to lobby the EPA directly had at least tangential business before the agency.

Among them is industrial equipment manufacturer Stanley Black & Decker, which is currently in litigation with the EPA over its own environmental liabilities. In 2014, the EPA ordered the company to pay $104 million in cleanup costs at a superfund site in Rhode Island. Black & Decker disputed the ruling, but estimated in its most recent annual shareholder report, it expects that it may eventually have to pay between $68 million and $140 million in remediation costs at the site. The case is currently working its way through federal court, an EPA official confirmed to The Daily Beast. And Pruitt himself has directly weighed in on the matter, elevating the superfund site as a target for immediate and intense attention.

Hart’s other clients include Cheniere Energy, which as Fox’s Ed Henry noted operates liquified natural gas terminals on the Gulf Coast and is reportedly one of the best positioned companies for Pruitt’s American gas export campaign. “Steve has never represented them,” Pruitt insisted to Henry.

In fact, lobbying disclosure records show that Hart has personally represented Cheniere since Williams & Jensen signed the company as a client in 2004.

In a separate interview with The Daily Signal, the news arm of the conservative Heritage Foundation, Pruitt claimed that “[Hart’s] firm represents these [energy industry] clients, not him. There has been no connection whatsoever in that regard.”

In fact, Hart represents numerous firms in the energy space, in addition to Cheniere. Black & Decker subsidiary Stanley Oil and Gas “provides world-class pipeline services and equipment in more than 100 countries, offshore and onshore,” according to its website. Another Hart client, Smithfield Foods, manufactures energy through the use of animal waste collected at its hog production facilities. Hart’s lobbying on behalf of the company routinely includes advocacy on energy policy issues.

Other Hart clients have had business before the EPA on either ceremonial or non-energy related matters. Hart represents the Coca-Cola Company, which has landfill and bottling operations that have fallen under the EPA’s purview. Hart represents United Airlines, which is involved in an aircraft drinking rule program for which the EPA—while Pruitt was staying at Hart’s condo—issued self-inspection requirements. And until December 31 of last year, Hart represented the American Automotive Policy Council, a trade group formed by Chrysler, Ford Motor Company and General Motors; automakers that have numerous policy interests the overlap with the chief environmental protection agency in America.

A request for comment to Hart was not returned seeking clarity as to what, if anything, he did to advance his clients interests before the EPA. In some cases, however, it is clear that his clients fared poorly. This past week, for example, Pruitt announced that he would be rolling back Obama-era car emissions standards, a policy that both Ford and GM have been vocal about not supporting, as one plugged-in Hill source explained.

The EPA did not return a request for comment.