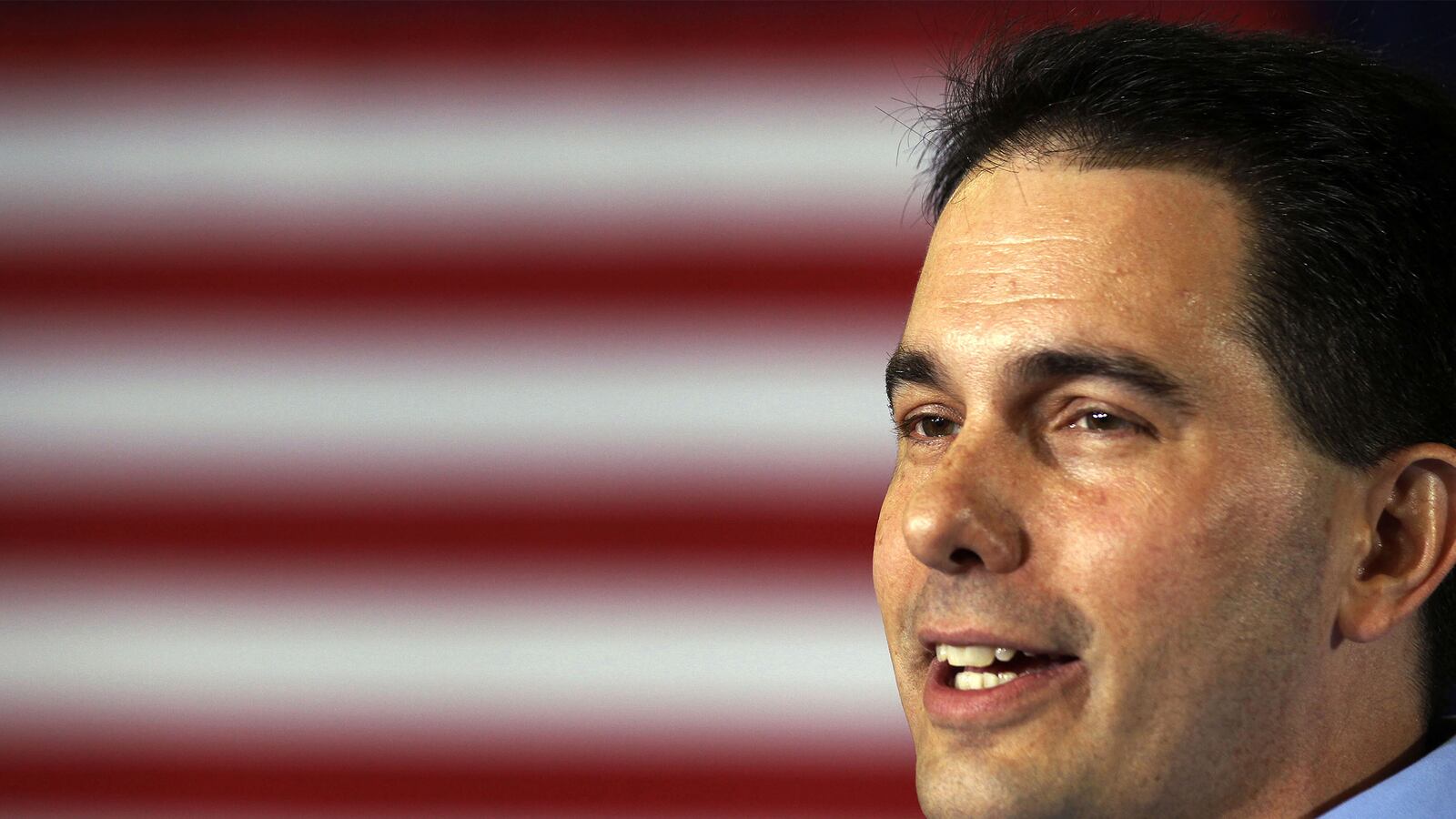

It has been more than a decade, but when David Riemer talks about Scott Walker, his voice still shakes with anger and exasperation.

“He thinks that God is on his side and so that gives him the right to lie, to dodge, to make promises and not keep them,” said Riemer, now a senior fellow a the Community Advocates Public Policy Institute, a think tank dedicated to reducing poverty in Wisconsin.

Back in 2004, Riemer ran against Walker, then a first-term county executive of Milwaukee who had ridden into office on the back of a pension scandal, pledging that any of his office’s hires would sign a waiver forgoing recently enacted lavish benefits and sweeteners.

Riemer, an adviser to two Wisconsin governors and a former budget director of the city of Milwaukee, filed an open-records request in an effort find out if that promise had been kept. Turns out, it hadn’t; in response to the open-records request, a handful of top staffers hastily added their name to a list stating that they had signed the waiver. The list didn’t have a date on it, though, and wasn’t an official waiver anyway, merely a piece of paper indicating that signatories had signed a wavier previously.

In a letter to the attorney general’s office after the election, and after Walker’s office had eventually complied with the open-records request, Riemer wrote that Walker’s intention had been “to fool me, as Mr. Walker’s primary opponent in the political campaign for County Executive; to fool the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel; and to fool the voters and the public. The deception worked. We were all fooled.”

The attorney general declined to prosecute but accused Walker of “chicanery.”

And that was not all.

In the course of the campaign, Walker’s team ran a radio ad accusing Riemer of engineering a pension settlement to a series of lawsuits that cost the county millions of dollars. In fact, the lawsuits predated Riemer’s tenure with the county, and his reforms helped save the city up to $25 million a year. When pressed, according to the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, Walker conceded that “the ad’s assertion is not correct as stated,” but he refused to stop running it.

“I have never in my life seen anything like it,” Riemer, who ended up losing the election by nearly 15 percentage points, said. “What kind of person admits that what they are doing is wrong but won’t change it? There is a fundamental character flaw here.”

Walker is now on the cusp of announcing a run for president, and early polls show him as a front-runner to become the Republican nominee. And part of his appeal to the Republican faithful is his record of success in political campaigns and in public office. This is someone, after all, who won four consecutive terms in the state legislature before winning three county executive races in the Democratic-leaning Milwaukee County and three races for governor in blue-hued Wisconsin. He also became the first governor in American history to survive a recall. And unlike some Republicans in Democratic territory who hew to the center after Election Day, Walker tacked sharply to the right while in office, winning him plaudits from conservative leaders as a true believer.

But longtime Walker-watchers in Wisconsin say that behind Walker’s success is a long record of bending campaign laws just to their breaking point.

“Scott Walker is politics incarnate, with an unslakable thirst for political power and an eye on the next election,” said Mike Browne, the deputy director of One Wisconsin Now, a liberal advocacy group. “Throughout his nearly quarter-century career running for office, he’s shown he’ll do whatever he thinks he needs to do to win, letter or spirit of the laws be damned.”

Most notably, Walker has been ensnared in a pair of so-called John Doe investigations. In the first, while looking into missing funds from a veterans’ charity run out of Walker’s county executive office, investigators discovered that his staff had set up a secretive Internet system in his government office to allow them to do political work on the taxpayer’s dime. Investigators also found that a railroad executive with business before the state had set up a straw donor scheme enabling his employees to donate to the future governor.

The investigation didn’t touch Walker, but a deputy chief of staff was sentenced to six months in jail. Another was convicted of embezzlement after it was discovered that he used funds stolen from the veterans’ charity to set up Walker for Governor campaign websites. Another top staffer received one year of probation and a $1,000 fine after cooperating with investigators.

The second John Doe investigation is ongoing and focuses on whether Walker’s campaign illegally coordinated with the Club for Growth during his 2012 recall campaign. According to heavily redacted documents released last week, Walker’s defense argues that such coordination was not illegal because Walker was not an official candidate until April of that year—a mere two months before voters went to the polls and while Walker was raising and spending millions of dollars to ward off his Democratic opponent.

Walker’s trouble with campaign rules began even before he embarked on a political career in earnest. As a sophomore at Marquette University in Milwaukee, he lost a bid for student body president in a race that was marred by allegations that Walker improperly campaigned before officially registering his campaign, that he failed to properly register his campaign workers, and that he went door-to-door to hand out fliers in violation of campus policy. More seriously, after the school paper endorsed Walker’s opponent, stacks of newspapers went missing, and the Walker operation was accused of engineering the theft.

Walker dropped out of Marquette just before he was set to graduate and promptly mounted a campaign against Gwen Moore, a one-term state assemblywoman. In an interview, Moore, now a member of Congress, said her Republican colleagues at the time told her that the reason Walker was running was that even though the district was majority Democratic, “the majority voting-age population was white.

“He would say his hero was Ronald Reagan. Lee Atwater, Ronald Reagan, that was the regime he looked up to, and he ran a perfect racial dog whistle campaign,” Moore said.

The campaign literature, she recalled, featured “guns, gangs, drugs, and urban unrest.”

“I cried,” she said. “I thought I was being associated with the worst elements of the community. I couldn’t believe what a jerk he was. I was new to politics. I didn’t think it was fair game for them to say anything about you whether it was provable or not.”

Walker lost decisively, moved to a new district, and served nearly a decade in the legislature before running for county executive. While in office, he was repeatedly dogged by failures to properly file campaign finance reports, including leaving off the occupation of more than 50 donors who gave more than $100 in violation of state laws.

Failure to list a donor’s occupation is a problem that Walker’s numerous campaigns have encountered frequently. When he first explored a run for governor in 2006, the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, a nonpartisan watchdog group that pushes for clean elections, found that 114 donations totaling more than $75,000 failed to list the occupation or employer. In 2008, Walker’s office stopped filing its campaign finance reports electronically, which made life harder for watchdogs, but still in 2009, One Wisconsin Now found that $170,000 worth of contributions were not listed properly, including two contributions of $10,000, the maximum amount allowed by law. The next year, the group found that more than $500,000 in contributions was improperly reported.

In 2005, two Democratic county supervisors filed an ethics complaint with the elections board against Walker for using his campaign arm, Friends of Scott Walker, to robo-call against them on behalf of his budget without disclosing who was beyond the calls.

The elections board ended up fining Walker $5,000, then the second-largest such fine in state history.

But it was not the first time Walker’s name would appear before the state elections board. Since 2010, when he first began exploring a gubernatorial run in earnest, the state Democratic Party has filed seven ethics complaints against him.

The earliest cites a series of motorcycle rides Walker would take around the state while county executive, ostensibly to promote tourism to Milwaukee but which critics said was little more than a way for Walker to introduce himself to voters around the state (or beyond—Walker twice traveled to Minnesota on his annual Harley ride and once to the early caucus state of Iowa).

Twice the ride was sponsored by AirTran Airways, a low-cost air carrier that at the time had a request pending before the county commission for concourse space at the Milwaukee airport. The sponsorship led critics to accuse the candidate of extracting an in-kind donation from a corporation. According to the complaint, “It was not Milwaukee County logos…that lavished and marked everyone of the three dozen stops on the tour. It was signs, flags and standards of Air Tran that dominated every single venue on Walker’s tour.”

The claim that the trip was just for Walker to promote Walker and not Milwaukee County was given credence, the complaint alleges, when in 2010 it was rescheduled to coincide with the date and location of the state Republican convention, allowing Walker to roar in to the convention on the back of his Harley. Plus, the complaint notes that Walker was accompanied by Tim Russell, a longtime Walker insider—and the one who ended up going to prison for stealing from the veterans’ charity—who frequently moved between campaign and governmental positions. At the time of the 2010 ride, Russell was the administrator of the county’s housing department.

“Any reasonable person would conclude that Housing has nothing to do with tourism—Russell’s presence indicates that the ride was in fact illegal campaign activity,” the complaint states.

Another complaint alleges that right-wing outside groups like the Koch brothers-backed Americans for Prosperity were illegally coordinating with Walker’s recall campaign. The CEO of one such group, the Bradley Foundation, was Walker’s campaign chairman, and the chairman of the board of the MacIver Institute for Public Policy, a conservative think tank, had given $16,500 to Walker’s various campaigns.

A third complaint asks the Government Accountability Board to look into Walker’s legal defense fund, one that he has poured $60,000 of his campaign money into, though state law says such funds can be used only for a candidate or public official who is being investigated or who has an agent who is being investigated. Walker has denied repeatedly that he is a target of the John Doe investigation.

A fourth complaint alleges that in the spring of his recall campaign, in the wake of a federal Bureau of Labor Statistics release that showed that Wisconsin was the only state to post “statistically significant” job losses in the previous 12 months, the Walker administration expedited the release of its own jobs figures, which used a different metric from the widely used BLS metric. Walker’s numbers showed that the state added jobs, and moments after releasing the numbers, his recall campaign launched a blitz of television and radio ads touting them—proof, the complaint alleges, of coordination between the government and political side of Walker’s office.

A fifth complaint, filed just this year, accuses Walker of dissembling when he claimed that his recent trip to the United Kingdom was for official business and used public funds to promote trade between Wisconsin and the U.K. The visit was widely seen as a chance for Walker to bolster his foreign policy credentials, and Walker refused to answer media questions while in the United Kingdom.

According to a Democratic Party official, five of the complaints are still pending. Two more were dismissed. One alleged that Walker brought Republican super pollster Frank Luntz into the state capitol during the protests against the governor’s efforts to end collective bargaining for public employees in the state. Another alleged that Walker tried to coordinate with the Koch brothers directly by discussing by phone how he was handling the protesters, including planting “troublemakers” within their midst. (That call turned out to be a prank.)

“The blatant disregard for campaign finance and ethics laws we’ve seen from Scott Walker over the entirety of his career in elected office is unprecedented in Wisconsin politics,” said Melissa Baldauff, communications director for the Wisconsin Democratic Party. “Never before has a Wisconsin governor required a criminal defense fund, the donors to which still haven’t been disclosed, or been alleged by prosecutors to be at the center of a nationwide ‘criminal scheme.’"

In a statement, Kirsten Kukowski, a spokeswoman for the governor, said, “Governor Walker has championed big, bold reforms that the left clearly doesn’t like, but he’s won three times in four years because of his results for the people of Wisconsin.”

Few in Wisconsin think Walker will somehow be brought down by any of the complaints. To the exasperation of state Democrats, none of these allegations seem to have much slowed his steady ascent through the political ranks. Now that he is running for president, Walker finds himself facing a new set of campaign finance regulations.

In a presidential campaign, many would-be candidates who are exploring a run take great pains not to admit that they are candidates for office. To do so would mean that they could run afoul of fundraising laws that forbid coordination between candidates and the outside groups supporting them. Jeb Bush, for example, has dismissed questions about what he would do as president by noting that he is not yet a candidate and wouldn’t want to suddenly trigger a campaign. When he did acknowledge that he was running, Bush promptly backtracked.

Walker has no such apparent qualms, referring to himself several times as “a candidate” and talking about how his sons may take time off from college to campaign with him, even though no such campaign officially exists.

Democrats have filed complaints to the Federal Election Commission. They are unlikely to go anywhere.