The shooting incident at the White House is a reminder that the presidential security bubble is often put to the test.

Of course, the White House is a tough target. There is the bulletproof glass, the barriers, the fence, the sensors. Secret Service officers are standing guard, walking patrol, riding bicycles, driving cars, or leading bomb-sniffing dogs. It’s been reported there’s an antiaircraft system ready to take out planes that might try to launch 9/11-style suicide attacks.

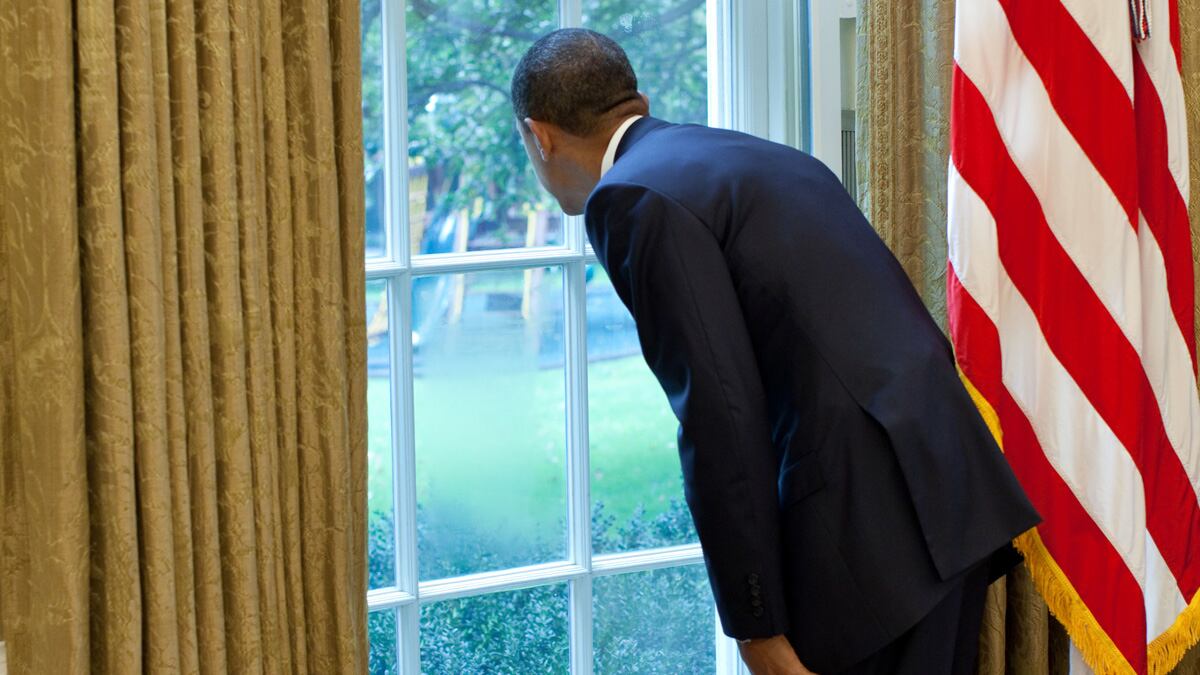

But none of that, of course, stopped the alleged shooter last week, Oscar Ramiro Ortega-Hernandez, a 21-year-old student. Officials say he managed to hit, though not to penetrate, a White House window with a rifle shot from Constitution Avenue. Ortega, who seems unbalanced, has allegedly referred to President Obama as “the Antichrist” or “the devil,” and on tape he called himself a “modern-day Jesus Christ.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Secret Service spokesman Edwin Donovan emphasized in an interview with The Daily Beast that the shooter was about 800 yards away: “It’s important to realize that this individual was half a mile from the White House.” The president wasn’t even in the White House at the time. And Donovan pointed out that security responded quickly: “When the incident occurred, within a couple of minutes the car was recovered, the weapon was recovered.” Still, it took days to get Ortega into custody after the shooting.

Stopping anyone from shooting anywhere near the White House does seem fanciful. “At any given day some lunatic may fancy themselves Jesus and may fancy the president the Antichrist,” said John Adler, national president of the Federal Law Enforcement Officers Association. “We can’t control that.” Since 2010, new funding has helped the Secret Service uniformed division stay staffed adequately, he said.

But the shooting might be a reminder that even if this gunman didn’t do much damage, trained and dedicated attackers might be more of a threat.

Security breaches at the White House have taken all forms over the years. There have been attempted air assaults, like a 1974 incident with a stolen U.S. Army helicopter. In 1994, a man who had used alcohol and crack cocaine crashed a stolen Cessna on the South Lawn. Attackers have come with guns, with knives, with bombs. There have been the fence jumpers and gatecrashers. There have even been party crashers, like the notorious Salahis, the couple who popped up at a state dinner in 2009.

But the thing that makes the White House potentially vulnerable is what is rooted most strongly in its history: it was never designed as a fortress or a palace. Instead, the plan for the White House, and indeed the city around it, was for it to be accessible to Americans who were interested in their government.

“It’s always a balance between access and security,” the Secret Service’s Donovan explained. “The White House is an iconic structure in the United States.”

For most of its history, the White House was open to ordinary Americans to a degree that is now unimaginable. A 1995 review by the Treasury Department provides an intriguing historical insight into the White House as seen through the distinct prism of security experts. “It was President Jefferson himself,” the report says, “who began the liberal practice of throwing open the doors to the Mansion each day so that visitors might freely browse the State Rooms.”

Things stayed open for almost a century and a half. “It was not until World War II,” the report says, “that free public access to the White House grounds during daylight hours was finally ended. Security measures would never again be as relaxed as they were before the war.”

The security buildup evolved quickly after that against the backdrop of the Cold War, the Kennedy assassination, and then the evolving terrorist threats. In 1983, the Beirut Marine Corps barracks bombing prompted the Secret Service to install concrete barriers around the perimeter.

Then, in 1995, after the bombing of the Oklahoma City federal building, and the plane crash on the South Lawn, the federal government shut down car traffic on Pennsylvania Avenue in front of the White House.

The move seemed intolerable at the time to civil libertarians. The Washington Post called it “a concession to terrorism that should not be made permanent…The avenue stayed open despite a British invasion, and despite street riots in the 1960s. But now, because of the devastation in Oklahoma City, the history of Pennsylvania Avenue may be erased by bulldozers.”Some in Congress denounced the move. “Dismantle the barricades, Mr. President,” demanded then-Senator Rod Grams (R-MS), “and may the souls of the patriots who founded this nation in freedom’s name take pity on us if we don’t.”

Over 16 years, the outrage over the security measure has disappeared, and despite all the lofty rhetoric, things have tightened up since then.