Richard Mosse’s photographs capture the darkness of war in vivid color: warlords and rebels armed with AK-47s are tinted with bubble gum and magenta pinks. Stripped skulls lie in the blood-red grass of rolling hills and the haunting stares of huddled women are framed with dusky purples. It’s an uncomfortable yet magnetic paradox, which resonates through Mosse’s work. Quite literally, he’s depicting the conflict in Africa’s Democratic Republic of the Congo in a whole new light.

The secret behind the surreal color palette is Mosse’s use of the discontinued Kodak film, Aerochrome. Developed by military surveillance during the Cold War to detect enemy camouflage, the film registers the invisible spectrum of infrared light, tingeing portraits and landscapes with psychedelic hues of pink, red, and lilac. “It made sense to me metaphorically. This war is a hidden tragedy, and in that sense it’s invisible,” Mosse explained. “Making the conflict visible for ordinary people to see is at the heart of this project.”

From June 1 to November 24, 32-year-old Mosse will represent his home country of Ireland at the 55th-annual Venice Biennale with his latest work, The Enclave. Anna O’Sullivan, director of the Butler Gallery in Kilkenny and Ireland’s commissioner curator for Venice 2013, describes the project as a “highly ambitious six-channel multimedia installation on the subject of the ongoing conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.” Mosse says that the exhibition will blend film, photography, and sound to create a hauntingly immersive experience of the eastern region’s devastated villages.

The International Rescue Committee estimates that 5.4 million people have been killed or have died of war-related causes in the conflict in the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo since it first began in 1996. Though the war officially ended in 2002, fighting is still rife, especially within the mineral-rich eastern region. Rape, looting, and massacres are frequent tactics of intimidation among the different factions. UNICEF reported that, to date, 20 percent of the country’s children still die before the age of 5 and hundreds of thousands of women have been raped. “The cancer of conflict is getting more and more problematic. It’s really very convoluted, very incomprehensible,” says Mosse, who has made six journeys to the region, each for about two months. “Corruption has really undermined any sense of a civic identity.” He adds, “It’s truly a Hobbesian state of war where everyone’s out for himself.”

Mosse is no stranger to photographing conflict; since graduating from Goldsmiths in London and Yale School of Art, he has traveled to Iraq, Iran, Gaza, the former Yugoslavia, and Pakistan. But Congo has dominated his work for the last three years. Mosse’s initial Congo project “INFRA” garnered a viral hype within months of its first opening in New York. Aperture Foundation and Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting went on to publish a monograph of the work, which was rated one of the top photo books of the year.

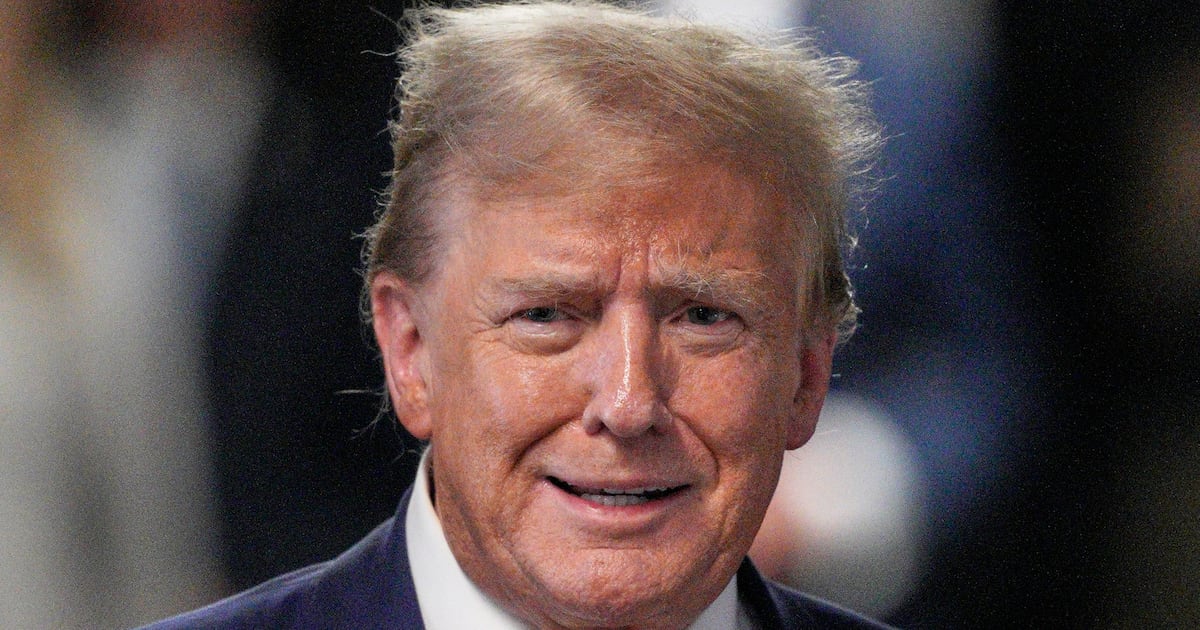

With his sandy blonde hair, blue eyes, and lilting Irish tones, Mosse clearly stuck out as a foreigner in the Congo region. Embedding with the rebels was a delicate process that took months of research and work with different fixers. “Often they’re very suspicious at the beginning,” says Mosse, who has photographed notorious militia groups such as the M23 rebels, the CNDP, and the FDLR. “But essentially everyone wants to tell their story, because they’re all fighting for something.”

“I think this whole project is about dreams underwritten by nightmares,” said Mosse, recalling a harrowing scene he had encountered driving up to a small Congolese town named Masisi. It was bad weather and the roads were almost impassable, but upon arriving at the camp he and his translator were met by crowds of people, standing in silence. They had walked for two hours from their village, carrying the bodies of six massacre victims to show to the town’s governor.

“They were all women and children. The women had been raped before being killed with machetes,” recalled Mosse. “The youngest was a boy of 3 years old who had been killed with a spear through his face, leaving his brain exposed. His eyes were still intact and they were staring back at me.” He went silent before continuing. “It’s something that I’ll never forget—it’s worse than nightmares.”

The surreal quality of Mosse’s photographs allows the viewer to take a step back into a more reflective space. Rebels and villagers stare out from the psychedelic images with unfiltered defiance. “They have a very unusual response to the lens,” Mosse said. “They’re very suspicious of the camera, so it becomes a kind of face-off situation. Its very different to the glib self-conscious reaction to photography that we have in the West.”

Mosse is careful not to label himself as a photojournalist, despite taking documentary-style photographs. “I’m an artist who works in war zones,” he said. He has received his fair share of reproach for the controversial nature of his images, critics questioning both his right to tell the story of the Congolese and his unsettling distortion of realism. Mosse, however, remains defiant. “Political correctness is a real disease. I’ve learned not to be scared of offending people,” he said. “I don’t want to lock down what you’re meant to feel.” Art critic Christian Viveros-Faune of Art in America Magazine writes that the photographs are “essentially vibrant, gorgeous pictures of hell on earth,” and Mosse encourages the audience to explore the contradiction further. Many of his photographic titles are references to Jimi Hendrix, Bob Dylan, and Steve Reich song lyrics, a jarring link to the Kodak film’s popularity on album covers back in the ’70s. Mosse argues that this gives space for imagination and frees up people’s interpretations, allowing them to focus on the questions as opposed to the answers.

Representing Ireland at the Venice Biennale has been a lifelong dream for Mosse. “I couldn’t believe it when we got selected—my heart broke,” he said. “Now I’m a man without dreams,” he added with a laugh. He’s quick to acknowledge that his Irish heritage has played an integral part in shaping his fascination with conflict. He recalled the impact he felt as a child from rural Kilkenny when visiting Northern Ireland in 1980s during the Troubles. “I found it very powerful—it was haunting” he recalled slowly. He described crossing the heavily guarded Belfast boarders into the bleak, gray city with surveillance cameras watching from every angle. “It’s easier to talk about yourself through other people’s problems,” he said. “I’ve tried to make work in Ireland and it’s impossible. It’s too close to the heart.”