LAS VEGAS—Lee Goodman had a question to ask as he walked slowly in front of the Sands Expo Convention Center.

“When?”

When was the firearms industry going to address mass shootings?

Goodman balanced a sign stapled to a wood handle on his shoulder. The sign listed the mass shootings from Columbine to Sandy Hook and Las Vegas. On top of the purple sign in block letters was “If not now…” and at the bottom of the list of 11 shootings was his question.

“When?”

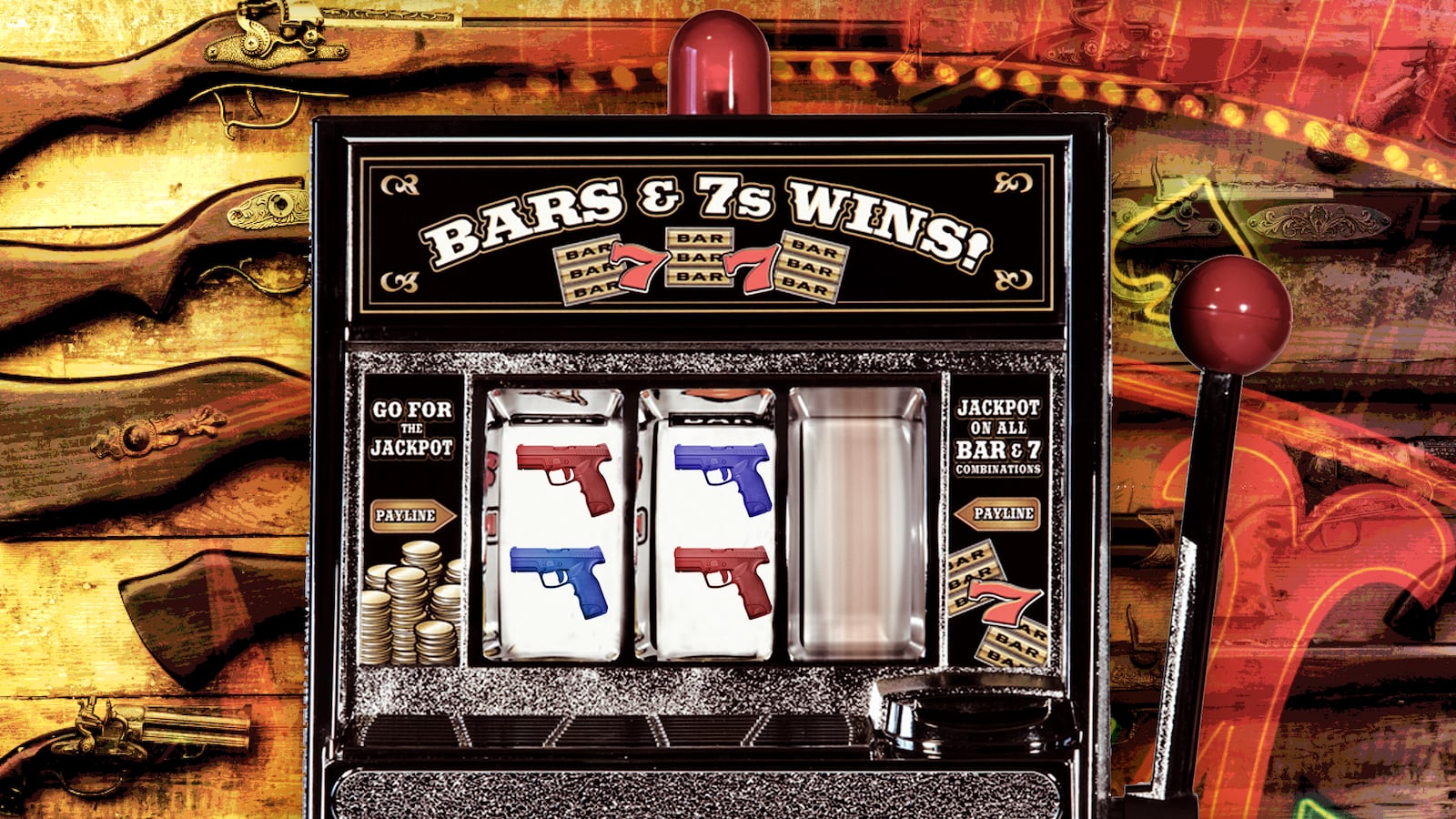

If there was ever a time and a place for the gun control community to ask that question it was at the annual SHOT (Shooting, Hunting, Outdoor Trade) show—America’s annual firearms trade show—in Las Vegas. This year it was held at the end of January about three miles from the Mandalay Bay hotel and casino where Stephen Paddock fired over a thousand rounds into a crowd of 22,000 people attending a country music festival. Fifty-eight people were killed and about 500 were wounded.

You’d think the SHOT show would attract protesters just three and a half months after America’s worst mass shooting. But for all the VegasStrong hashtags on signs and T-shirts on the Las Vegas Strip, only three protesters showed and Goodman, the organizer, was from out of town.

“I couldn’t stay away,” Goodman, a retired lawyer from Chicago, said as local TV cameras tracked his every move. “Even if I was the only guy, I was going to be there.”

Onlookers heading into the show either ignored Goodman or shook their heads.“Big showing for the protest,” one attendee said. “Good turn out.”

For attendees like Jon Wayne Taylor, who describes himself as an “old school gun nut,” SHOT show isn’t political, it’s about business. A place for the gun industry to show off the latest and greatest in firearms and accessories.

But Taylor – who owns his own Texas-based firearms parts company and writes about guns for The Truth About Guns—said even if lawmakers followed Goodman’s lead and passed a law that somehow regulated the ownership of guns or ammunition, it is unlikely enforcement would work.

“I’m not going to comply,” he said.

Other gun owners echoed that sentiment. Fire arms are protected under the Bill of Rights and gun owners like Taylor won’t accept any limitations on their rights.

Which takes us back to Goodman’s protest. If gun control wasn’t possible after Sandy Hook or Mandalay Bay, when will it ever be possible?

If the SHOT Show proves anything, firearms are and always have been woven into the fabric of American culture. Be it your grandfather’s shotgun or your mother’s Modern Sporting Rifle (MSR), guns are as American as the flag.

Lean with a salt-n-pepper goatee, Taylor leads the way into the show with a green Yeti coffee cup in hand. He seems to know everyone, stopping to talk with passersby and reps at the booths.

Taylor comes to the SHOT show wearing two hats. He is looking for fabrication machines for his gun parts business and the latest news from the industry for his readers.

To the untrained eye, most of the displays show off the MSR—an AR-15 style rifle that looks like a slicker M-16. The gun is by far the top-selling rifle in the United States. The National Rifle Association estimates Americans own more than 8 million MSRs.

Because of the rifle’s availability, it has been used in several mass shootings including Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012, the Pulse nightclub in Orlando and the Mandalay Bay, and the Texas church shootings last year.

Walking through the show it was easy to spot several versions with varied sizes, colors, and even custom paint jobs. Taylor called it a “Barbie doll for grownups” because there are dozens of ways to customize the rifle from the length of the barrel to the caliber of the bullet. A rail system lets gun owners mount flashlights and lasers for increased accuracy. Taylor says his mother owns an MSR. She is only 90 pounds, but the rifles are easy to use and have little recoil.

Taylor’s first stop is Daniel Defense. The Black Creek, Georgia based firearms company’s booth dominated one row of the show. Displayed on the booth’s walls were different variants of the MSR. Some with long barrels. Others had shorter barrels and looked more compact. Taylor set his coffee cup down on the booth’s thick carpet and broke down a few of the weapons showing how the same looking rifle can shoot different caliber rounds.

Two years ago, Taylor said demand for MSRs hit its highest just before the election. Everyone expected Hillary Clinton to win and Democrats sell guns.

“We’ve hit the bottom (of demand,” Taylor said. “Everybody made tons of them and now they’re sitting on tons of inventory.”

But guns sales have lagged since President Trump’s victory last year. With no fear of new gun control measures from a Democratic White House on the horizon, there was little motivation for buyers to stock up.

"The hunter doesn't care who's president,” Tom Jenkins from Nova Firearms in McLean, Va., told NPR last year. “The revolver shooter or the target shooter or the competition shooter really didn't care who was president. It's the self-defense market and the people think certain guns may be tied to politics."

The myth of the government coming for a private citizen’s guns doesn’t work anymore. One SHOT show veteran said last year the firearms industry was spending money like a drunken sailor.

“This year is the hangover,” he said.

But don’t tell Zev Technologies, whose booth was set up near Daniels Defense.

When Gerald Handl, the company’s trade show coordinator, joined the Zev Technologies, there were only three other employees. Now the company has 100 employees in two states.

“I only see us expanding more and more,” said Gerald Handl.

Handl said sales are strong and the industry continues to attract new and old buyers. Handl said the show is a good place for manufacturers and distributors preview the next generation of guns and accessories and book sales for the first quarter, Handl said.

“This is the all in one place release party,” Handl said.

SHOT is not open to the public. Only dealers, manufacturers and the firearms trade press have access, but the National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF)—the trade group that represents firearms manufacturers—granted The Daily Beast access to the show.

David Chipman, a former federal agent turned senior policy adviser with former Rep. Gabby Giffords’ gun safety group told the Associated Press last week the “sheer scope and the vastness” of the show would shock the public.

He has a point.

The booths and exhibits stretch for 13 miles over three floors with almost 2,000 companies in attendance. Few of the companies only made guns.

“Everybody is making guns,” Taylor said as he showed me the different parts of the rifle. “The real money is in gun parts.”

The evidence was the countless booths hawking everything from custom rifle stocks to specialty optics . One booth had goggles for hunting and police dogs. Every type of ammunition maker was on hand. The newest hunting lines from Under Armour and Mossy Oak were on display. The latter had a huge spread made to look like a hunting cabin with several meeting rooms, thick carpet and free beef jerky (a welcome snack since the in-show snack bars were grossly overpriced).

The top floor of the SHOT show is where the bigger companies live. It’s prime real estate with two-story booths—most have meeting rooms at the top where deals are struck—with slick displays, thick carpet and flat screen TVs playing promos in a loop.

There are over 350 million guns in America, according to a Washington Post estimate in 2015. Firearms ownership is hard to pinpoint. Estimates come from the total number of guns made, imported and exported. A 2012 report to Congress estimated the number of guns in the United States at around 310 million in 2009, President Obama’s first year in office. But the SHOT Show is the only the sixth most attended show in Las Vegas.

This year’s show attracted an estimated 64,500 attendees with an overall economic impact of $127.2 million, according to the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority. Compared to the Consumer Electronics Show, which tops the list with 175,000 estimated attendees, the SHOT show is better than most, but on par with the World of Concrete show (about 60,000 attendees) held the same week.

On the floor, every sex, race, and creed are at the show. A man dressed in black loafers decorated with sequins and a pink sports coat presses past a guy wearing camouflage from head to toe. Women were well represented as both industry reps and buyers. There was no stereotypical gun owner.

Taylor grew up around firearms in a small town of goat ranchers about 40 miles from Austin in central Texas.

“My family stored guns under my crib,” Taylor said.

By 6 years old, he was hunting. He has hundreds of guns—everything from black powder rifles to an AK-47 he made by hand and uses to hunt pigs on his ranch in Texas.

“I grew up knowing a gun was a powerful tool,” he said. “It was a means to not get bitten by a snake and maybe get a deer to eat.”

When he joined the Army after the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, he was already a good shot. He joked that the M-16 he qualified on was less powerful than some of the rifles he grew up shooting.

“It felt like a toy,” he said.

Taylor deployed for almost two years to Afghanistan where he worked as an adviser with Afghan forces.

Taylor shoots about 2,000 rounds a month. For him, it is a Zen moment. He meditates daily, but shooting is different.

“I want all my focus solely on the target until the bullet appears there,” Taylor said. “That is my goal. The bullet is a thought propelled.”

Taylor called the “angst” about guns in society “purely emotional.” He fights the angst by hosting a Sunday shoot at his range in Texas. It is open to the public and Taylor teaches marksmanship and gun safety. Most leave with less fear of guns, he said.

A big surprise was the lack of politics at the show, despite a massive NRA booth on the first floor. There were no rallies supporting the 2nd Amendment. Little talk publicly about the mass shootings at either Mandalay Bay or the Marshall County High School in Kentucky, which happened the week of the show. For every one hundred people at the show, you might see a political t-shirt—one shirt had “I prefer dangerous freedom over peaceful slavery” printed on the back—but it never reached a level of trolling.

The gun owners I spoke with—most wanted to speak on background —didn’t come to the show to talk politics. That was the difference between Goodman, protesting outside, and those attending the show. Guns weren’t something to be feared. They weren’t inherently evil. Guns were a hobby, a tool or a legal commodity to be traded. Police departments and the military were side by side with gun store owners buying firearms and equipment.

“People spend a lot of money to come here to do business,” Taylor said.

The only guy talking politics was outside.

After about 45 minutes of interviews with the Associated Press, a local TV station and a documentary crew, the protest broke up. Media members outnumbered protestors even after Goodman was joined by two ladies—one held his extra sign. The whole protest took less than an hour. Goodman’s two fellow protesters left as he started to walk the three miles to the outdoor festival venue near the Mandalay Bay.

For the last 14 years, Goodman has advocated for gun control. It became a calling after he met a woman whose pregnant sister and husband were murdered by someone using a gun.

Nothing fazed Goodman as he walked against the tide of SHOT attendees. He ignored the sideways glances or shaking heads. The two sides passed in peace for the most part. A bearded man in a truck shouted at Goodman as he walked down Sands Boulevard.

“Get a fucking job.”

Goodman kept his eyes forward.“I’ve heard that one before,” he said with a chuckle.

At the corner of Sands Boulevard and Las Vegas Boulevard, Goodman stopped to give the local Fox affiliate an interview. A homeless man using a straw to drink beer from a 22 ounce can of Pabst Blue Ribbon stood and listened. After a few minutes, the man with a ratty gray beard shrugged.“I guess it’s his right,” he said. “That’s what makes America.”

To the locals, the SHOT Show—held the same week as conferences for the concrete industry and Adult films—was just another trade show in a town overrun by folks in name badges on lanyards.

The Fox reporter filmed Goodman walking a couple of blocks and then left. After the filming, Goodman paused in front of the Venetian to take in the fountains and faux canals meant to mimic Venice. He looked more like a tourist than a protestor. If he was disappointed in the turnout, it didn’t show.

“Look, you always want 100,000 people,” he said, walking alone toward the Mandalay Bay Hotel and Casino. “But if you get the word out, the gun industry knows I am there.”

He came with a message, which he repeated in every interview.

“The gun industry made money off of every gun and bullet used in (the Mandalay Bay) massacre,” he said. “Stop opposing every effort to reduce gun violence.”

Goodman soon disappeared into the crowd walking down the Las Vegas Strip. He wrote later on Facebook about his inability to change minds and how an onlooker on his way to Mandalay Bay answered his question.

When will the firearms industry address gun violence?

Never.