The impeachment trial of President Trump began in earnest on Tuesday—and the historic proceedings kicked off not with opening arguments in the case but with a bitter fight over the rules that will govern the process.

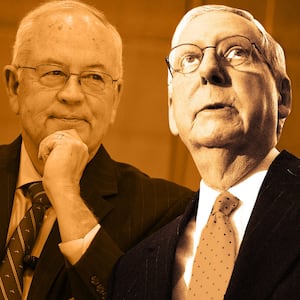

After weeks of private negotiations and public squabbling with Democrats, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) introduced his proposed rules for the trial on Monday night that, among other things, offered each side up to 24 hours of argument spread over the course of just two days each, stipulated that a vote was needed to enter the House’s body of evidence into the record, and mandated that additional witnesses and evidence could be voted upon only after the opposing sides finished outlining their cases.

“This is the fair roadmap for our trial,” McConnell said in his opening remarks on Tuesday, explaining they were modeled after those adopted by the Senate during the President Bill Clinton impeachment trial. “Fair is fair, the process was good enough for President Clinton and basic fairness dictates that it ought to be good enough for this president as well.”

But that “fair roadmap” hit a speed bump quickly after its unveiling, when it became clear that McConnell’s own members were “concerned” at the prospect of sitting on the floor of the Senate for 12-hour stretches for four days in a row.

In the hours leading up to the start of the trial, several Republican senators lobbied McConnell’s office for the changes. The two-day time period, which would have resulted in very late nights, were of particular concern to senior lawmakers who were worried how they would fare, according to two individuals familiar with those requests.

One GOP aide confirmed that senators expressed concern with the schedule at the party’s Tuesday lunch and McConnell responded to them.

Sen. Susan Collins (R-ME) applauded McConnell’s decision to alter the rules.

“Senator Collins and others raised concerns about the 24 hours of opening statements in 2 days and the admission of the House transcript in the record,” her spokesperson said in a statement. “Her position has been that the trial should follow the Clinton model as much as possible. She thinks these changes are a significant improvement.”

Democrats, however, claimed it was public pressure that forced the change. It is evidence, claimed Senate Minority Leader Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-NY), that Republican lawmakers would respond to public pressure and not obey the GOP leader at every turn.

“This idea that Mitch McConnell, whatever he does, every one of them will go along with,” Schumer said of his Republican colleagues, “doesn't seem to be happening.”

Asked about whether Democratic push had initiated the change, the GOP aide shot back, “If Democrats think they had anything to do with that, they should check with Justice Garland.”

Either way, those schedule tweaks are likely to come as a relief to members on both sides. Indeed—when the sun was still up and the trial just barely underway—several members of the chamber appeared to visibly nod off during Rep. Adam Schiff’s lengthy opening statement.

In that opening statement, Schiff (D-CA) decried the GOP comparison to the Clinton-era rules and the suggestion of fairness that comparison implies. Democrats point, for example, to the fact that under these rules, Republicans can file a motion to dismiss the trial at any time—even before a vote on whether to admit new evidence and call new witnesses.

With that concept still at the heart of McConnell’s rules, Democrats are set to vote against them in a vote to take place later Tuesday. In his speech urging a no vote, Schiff implored the Senate jurors to place fairness as their top concern and framed the rejection of McConnell’s rules as the first step toward fairness.

“Right now a great many, perhaps even most, Americans do not believe there will be a fair trial,” said Schiff. “They don’t believe that the Senate will be impartial. They believe that the result is pre-cooked, the president will be acquitted. … Let’s prove them wrong.”

The 11th-hour fine-tuning of the rules package reflects McConnell’s need to lock down the support of at least 51 of his 53 GOP senators in order to advance the trial’s ground rules without any Democratic input. He is still poised to earn that support.

Schumer's goal, however, is to make that vote as painful as possible for Republicans by first forcing votes on subpoenaing new evidence at the beginning of the trial. Schumer introduced an amendment on Tuesday afternoon to subpoena the White House for documents that were withheld during the House’s impeachment inquiry. He may introduce additional similar amendments later on.

However, even the handful of Republicans who are leaning toward voting for new witnesses and evidence, such as Sen. Mitt Romney (UT) and Collins, have said they only want to take that vote after House Democrats and the White House have completed their opening arguments.

When the Democrats’ amendments fail, the final vote to approve McConnell’s rule package is likely to take place late on Tuesday—setting up House Democrats to begin presenting their full case against Trump on Wednesday.

As they began what will be the first of several long days, lawmakers on both sides filed into the Senate chamber on Tuesday with various approved materials to pass the long hours. Democrats carried with them identical binders filled with reading material related to the trial—the only kind of material permitted in the chamber during the proceedings.

Republicans’ approaches varied by senator. Some took their seats only with small notepads; others took volumes of material—such as Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX), who brought with him a massive binder piled high with papers.

Despite the scorched-earth political warfare of the past few months, both sides opened the trial with a whiff of civility. Standing before Chief Justice John Roberts’ perch on the Senate floor, the president’s defense team met the Democratic impeachment managers in the middle and shook hands. The friendliness ended when Roberts inaugurated the Senate “as a court of impeachment.”