A week ago, the House’s lead Democratic prosecutor, Rep. Adam Schiff (D-CA), opened the Senate impeachment trial by saying the most important vote for the 100 jurors deciding President Trump’s fate would be the one calling for a real trial—one with additional witnesses and documents—not the one deciding on his removal.

On Tuesday, after some 40 hours of speeches, countless eye-rolls, pages upon pages of notes and a smattering of stifled yawns, senators were left grappling with the same question they began the process with: not whether to convict or acquit the president, but whether to gather more information first.

For a moment in politics so massive in scope and so sprinkled with major news breaks, the result has been remarkably little political movement at all.

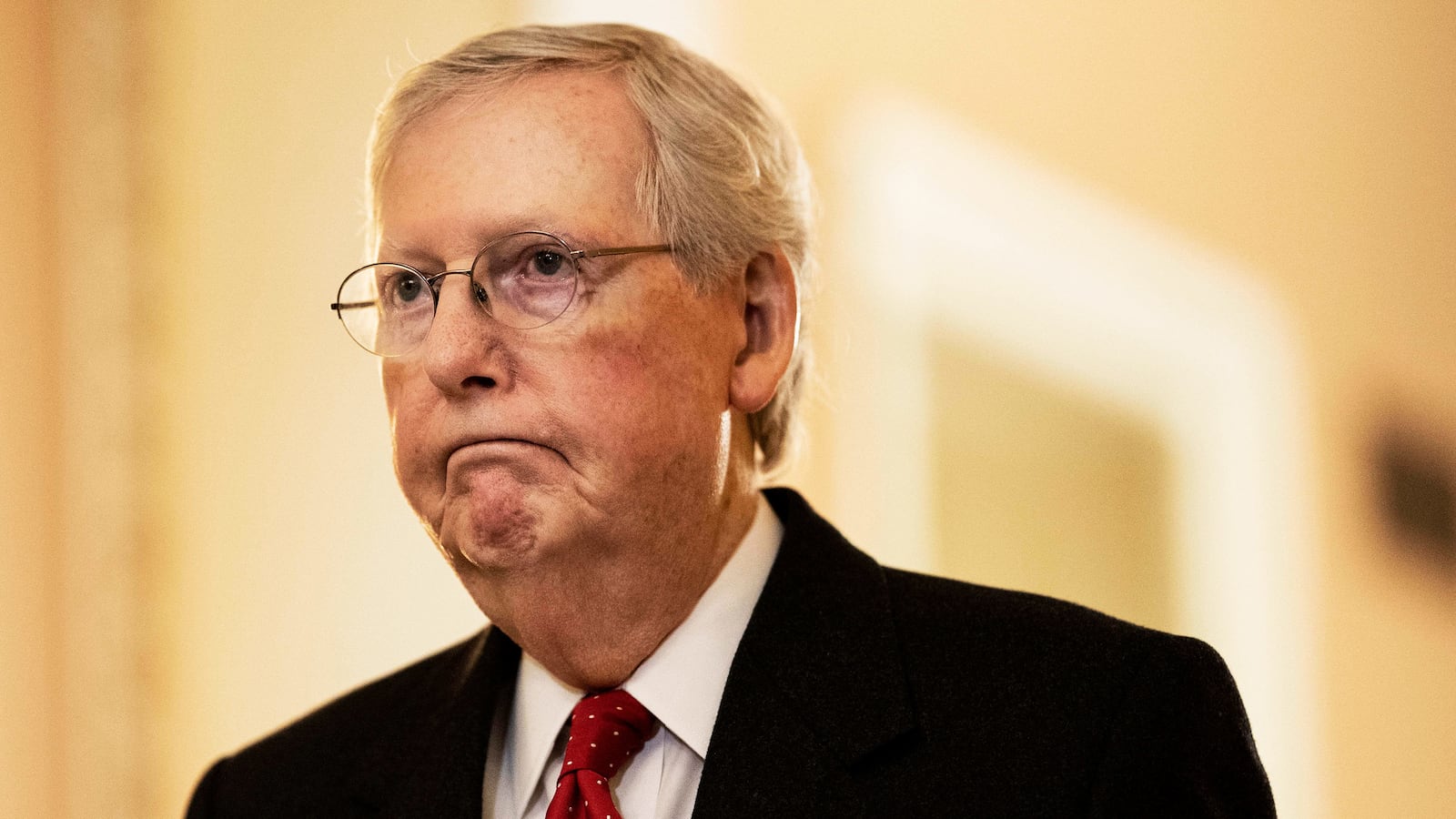

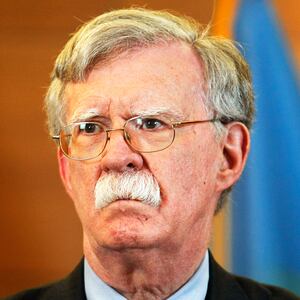

The latest evidence of a stalemate came this week after a pair of stories in The New York Times detailed that former National Security Advisor John Bolton’s upcoming book affirmed that Trump demanded a quid-pro-quo with Ukrainian counterparts. Such a revelation, bolstering the idea that the president leveraged military aid for domestic political gain, only increased the pressure on Republican senators to call on Bolton to testify. And by Tuesday afternoon, news had broken that Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) had told his conference he lacked the votes to defeat a witness request. But reaction to the admission seemed premature, as other reports suggested that enough lawmakers simply remained on the fence about how to vote, not that they were in favor of calling Bolton.

Indeed, the actual movement among Republicans appeared geared towards looking accommodating while extracting some gains in exchange. Late on Monday, Sen. Pat Toomey (R-PA) tried to resurrect an idea first proposed by Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) to have witness “reciprocity” between the two sides—one Republican witness for one Democratic witness. The new package didn’t seem to inspire a new result, as members of both parties shot it down.

Then on Tuesday Sen. James Lankford (R-OK) proposed that senators get a classified review of Bolton’s manuscript instead of actually hearing from the former advisor himself. The offer appeared to be a concession of sorts: obtain Bolton’s book, have senators review it in their secure basement facility, and allow the jurors to arrive at their own conclusions.

Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL), the Senate’s number two Democrat, said that he “of course” would support the idea of looking at the manuscript. But the Illinois Democrat, like others, wasn’t overwhelmed with the prospect of not having Bolton’s actual testimony. And no sooner had Durbin opened the door than his superior, Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-NY) closed it, calling the book proposal “absurd.”

“I think they’re trying to come up with a procedural fig leaf,” said Sen. Brian Schatz (D-HI) about the Bolton book suggestion. “The first idea was to trade relevant witnesses for irrelevant witnesses, and now they’re saying, how about if we get to take a look at a book manuscript in a classified setting? They have no leg to stand on, and that’s what this shows.”

It wasn’t entirely clear if Lankford’s idea even carried support among his GOP colleagues, many of whom seemed hell-bent instead on denying Bolton any shred of credibility. Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY), as staunch a GOP foe of the hawkish conservative there is in the Senate, trashed Trump’s former National Security Advisor as “an unhappy, disgruntled, fired employee who now has a motive—a multimillion dollar motive—to inflame the situation.”

Other Republicans seemed to suggest Democrats should be careful what they wish for. Senator Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) warned that, “One witness would probably lead to a lot of witnesses” and added there were probably 51 votes in the Senate GOP to compel testimony from the Bidens, the anonymous whistleblower, and other figures.

After the trial adjourned, GOP senators huddled privately to discuss next steps, leaving the meeting tight-lipped: “People are just thinking,” said Sen. Kevin Cramer (R-N.D.).

For Democrats, the question that confronted them was what else would be needed to jar Republican votes loose. One top House Democratic aide conceded a sense of “frustration” inside the caucus that Bolton’s manuscript had not yet convinced four Republican lawmakers to demand that he appear before Congress.

“But it's also not surprising to some extent,” the aide said. “As soon as people start to break there is a cascading effect and no one wants to be the deciding vote.”

There is still time for opinions to change. The next phase of the trial is a question-and-answer period, during which senators take turns posing questions to the House impeachment managers and the president’s defense. A vote on whether or not to call for new evidence could take place as early as Friday.

Though they tried mightily on Monday, Trump’s defense team could not ignore the Bolton news as they wrapped up their case. White House counsel Jay Sekulow tore into what he called “unsourced” reports about Bolton’s manuscript, arguing it was “inadmissible” as evidence.

Throughout Sekulow’s presentation, Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) sat straight in his chair with a small smile on his face. Across the aisle, Schumer sunk deeper into his chair, so much so he resembled a pile of clothes with only a hand protruding out of the top, covering his face.

The president and his team seemed content to spend their time trying to trigger the Democrats rather than win them over. Lead White House Counsel Pat Cipollone ended the White House’s pitch with C-SPAN footage of the impeachment managers—along with sitting senators including Ed Markey (D-MA) and Bob Menendez (D-NJ), and Schumer—speaking during the Clinton impeachment, making similar arguments to the ones Trump’s defenders make now.

“You were right,” Cipollone said, prompting guffaws from the GOP side of the chamber and disbelieving smiles from the Democrats. “But I’m afraid to say you were also prophetic.”

-- With reporting by Sam Stein