The U.S. Senate has rebuked the Trump administration, the Pentagon, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates by voting to end U.S. involvement in the war in Yemen, one of the world’s most catastrophic conflicts.

Though it is unlikely to become law during the final days of the current session of Congress, opponents of the nearly four-year war have delivered a vote of no-confidence in a campaign President Donald Trump’s key lieutenants have portrayed as crucial to containing Iranian aspirations for the Middle East.

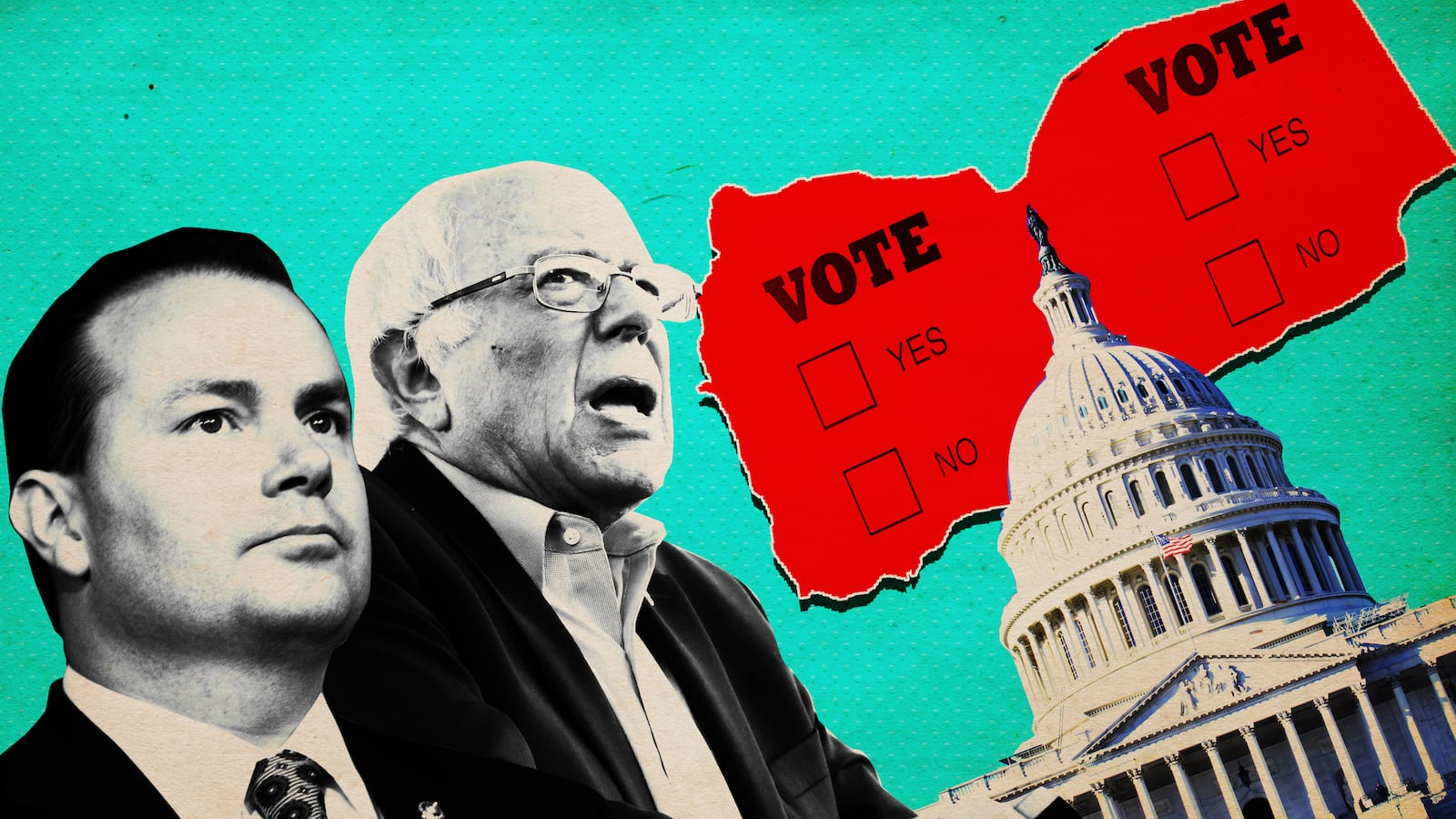

“As a result of the Saudi-UAE intervention, Yemen is now experiencing the worst humanitarian disaster in the world,” Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) said on the Senate floor, standing beside a massive poster of a severely malnourished Yemeni child. “The United States should not be supporting a catastrophic war led by a despotic regime.”

The vote for the anti-war resolution, which passed 56 to 41 on Thursday, has implications beyond Yemen. The Senate, for the first time in history, exercised its authority under the 45-year-old War Powers Resolution reasserting legislative control over war and peace—an unprecedented move since the post-Vietnam measure was enacted to rein in executive authorities over war-making. And it came despite Pentagon protests that the U.S. should not consider itself to be at war in Yemen at all.

“It is a historical moment... 45 years ago, members of the Congress passed the War Powers Act because they understood that the constitutional responsibility for war had slipped away from the Congress into the hands of the White House,” Sanders told The Daily Beast after the vote. “And they said that that’s wrong. But it’s taken us 45 years to finally act on that legislation in a positive way and to pass a resolution which ends U.S. participation in an unconstitutional war.”

All 49 Democrats voted for the resolution, and the handful of Republicans who backed it—Sens. Mike Lee (R-UT), Rand Paul (R-KY), Jerry Moran (R-KS), Susan Collins (R-ME), Steve Daines (R-MT), Jeff Flake (R-AZ), and Todd Young (R-IN)—put it over the top. The resolution would force the Trump administration to halt all U.S. military support to the Saudi-Emirati war in Yemen, although U.S. drone strikes and counterterrorism raids against al Qaeda targets would be unaffected. Lee and Sanders co-authored the resolution.

“There is no decision that is more fraught with moral peril than the decision made by a nation to go to war,” Lee said.

Outrage in the Senate over the brazen murder of Saudi dissident journalist and U.S. resident Jamal Khashoggi intermingled with a smaller bloc of legislative disgust over the devastation in Yemen. With U.S.-provided bombs and intelligence support, the Saudis and Emiratis have for nearly four years bombed civilians, blockaded ports and brought 14 million Yemenis to the brink of starvation. A cholera outbreak there is believed to be the world’s worst. The Trump administration argues that supporting its Saudi and Emirati allies is worth it because the Houthi rebels they are fighting are supported by regional enemy Iran. Last year, a State Department report found that beneficiaries of the chaos brought by the war include al Qaeda and the so-called Islamic State.

Hours before the Senate vote, the conflict’s combatants agreed in Stockholm to a U.N.-guaranteed ceasefire for the critical port of Hodeidah. The Houthi-held port is a major transit point for humanitarian goods, and it’s the scene of substantial, inconclusive combat. Negotiations on a political settlement for the war are expected next month.

“I think this resolution was going to pass even if Khashoggi was never murdered,” Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT), a longtime co-sponsor of the resolution, told reporters. “The momentum was just growing towards getting the United States out of this war. It was the [29] kids being killed in an intentional bombing of a school bus that flipped the few remaining Democrats to our side.”

Yet the Sanders-Lee resolution won’t pass this year in an obstinate House.

House Republicans on Wednesday used an unrelated piece of legislation to ensure that the war-powers resolution will not see the light of day this calendar year. The House adopted a rule in the annual farm bill that would prevent Democrats from forcing a vote until they re-take control of the House come January. The rule narrowly passed the House, 206 to 203.

It would be the second time in the wake of the Khashoggi slaying that House Republicans acted to neuter efforts to cease U.S. involvement in the war. Last month, House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI) used a legislative maneuver on another unrelated bill—this one to remove a category of wolf from the endangered-species list—to block Rep. Ro Khanna’s (D-CA) bipartisan resolution that complemented Sanders’ effort.

Accordingly, Sanders and his allies acknowledge that they wouldn’t be able to pass their resolution in the House—let alone override a presidential veto—meaning they wouldn’t be able to compel the end of the U.S. contribution to the Yemen war. Their immediate goal is to keep legislative momentum going into the next Congress, when they expect the likely next speaker, Nancy Pelosi (D-CA), to shepherd it through a Democratic-controlled House and hold enough Senate Republicans to clear the upper chamber, sending the proposal to Trump’s desk.

And they see a substantial victory in what they accomplished on Thursday. On Nov. 28, their resolution to get out of the Saudi-Emirati war coalition received an eye-opening 63 Senate votes to proceed to final consideration just hours after the secretaries of state and defense had implored senators to reject it. Thursday’s passage of the resolution represents a vanishingly rare instance of the Senate rejecting a war, a message the anti-war bloc believes will resonate in the White House, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi.

Even before the votes, the Pentagon ended an aspect of its contribution to the coalition, the refueling of Saudi warplanes in mid-air to permit them longer flight times. The Atlantic this week revealed that the U.S. wasn’t getting paid for the fuel.

The Senate’s rejection of a brutal war it has largely ignored for more than three years was prompted by the Trump administration’s embrace of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman—an architect of the Yemen war as defense minister—even after the CIA reportedly concluded that he ordered the grisly execution of Khashoggi. Senators briefed by the administration and eventually the CIA sounded incredulous over the administration’s studied agnosticism over the crown prince’s role.

“There’s not a smoking gun, there’s a smoking saw,” Lindsey Graham (R-SC) observed last week, a reference to Khashoggi’s dismemberment. The Yemen votes have been the only opportunities thus far for senators to express their disapproval of the crown prince and the murder.

The Senate also adopted a more direct rebuke of Saudi Arabia on Thursday, this time for the murder of Khashoggi. Sen. Bob Corker (R-TN), the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, sponsored a joint resolution to formally condemn the crown prince. On Wednesday, McConnell called it a “responsible alternative” to the Sanders-Lee proposal, and the Corker measure passed unanimously in the Senate.

It is unclear if the House plans to consider the Corker resolution, but CIA Director Gina Haspel briefed House leaders on Wednesday about the agency’s assessments on the Khashoggi murder. If senators’ reactions to the CIA findings are any indication, it is likely that the House, too, will consider Corker’s proposal to name the crown prince complicit in the murder.

An amendment to the Sanders-Lee resolution created the prospect of a debacle for the Pentagon that stretches far beyond Yemen.

Young, Republican of Indiana, won 58 votes for an amendment stating that the Senate considers the refueling activities the U.S. provided to Saudi warplanes to constitute participation in hostilities relevant to the War Powers Resolution. It flatly contradicts Defense Secretary James Mattis and senior Pentagon lawyers, who have argued for a year that Senate disavowal of the Yemen conflict is irrelevant, because the U.S. ought not to be considered a party to the war. If it isn’t, then Congress, through the War Powers Resolution, has no authority to make the military stop.

“The Saudi crown prince has unfortunately been left with the impression that he can get away with almost anything, including murder,” Young said.

The Pentagon position reflects that the military provides assistance worldwide to partner militaries, some of whom are involved in active conflict. Young’s amendment sets a potential precedent for expanding congressional authority over activities the Pentagon considers a step short of war. Corker estimated on the Senate floor that it might apply to “30 to 40 instances” of U.S. military activity abroad, though Corker and Young attempted to state for the record that they weren’t trying to set a precedent.

“It is a really big deal. The U.S. is engaged in activities like refueling and other seemingly lower level activities around the world,” said Andrea Prasow, the deputy Washington director of Human Rights Watch. “It participates in ways that certainly [the Department of Defense] doesn’t consider make it a party to armed conflict. If the Senate says it is, and engages in hostilities by refueling, that would mark a significant shift in both DOD’s and the public’s understanding of where the U.S. is potentially at war.”

As senators took to the floor on Thursday to debate the future of the U.S. contribution to the Saudi-Emirati war, Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-VT) said the Saudi military was “guilty of war crimes” and noted that the Trump administration had “lobbied hard against” the Sanders-Lee resolution. But “the outrage over Mohammed bin Salman,” Leahy contended, “finally boiled over.”