It should get our attention when a lone senator stops a popular piece of bipartisan legislation, blocking passage and opposing the prevailing opinion even in his own party.

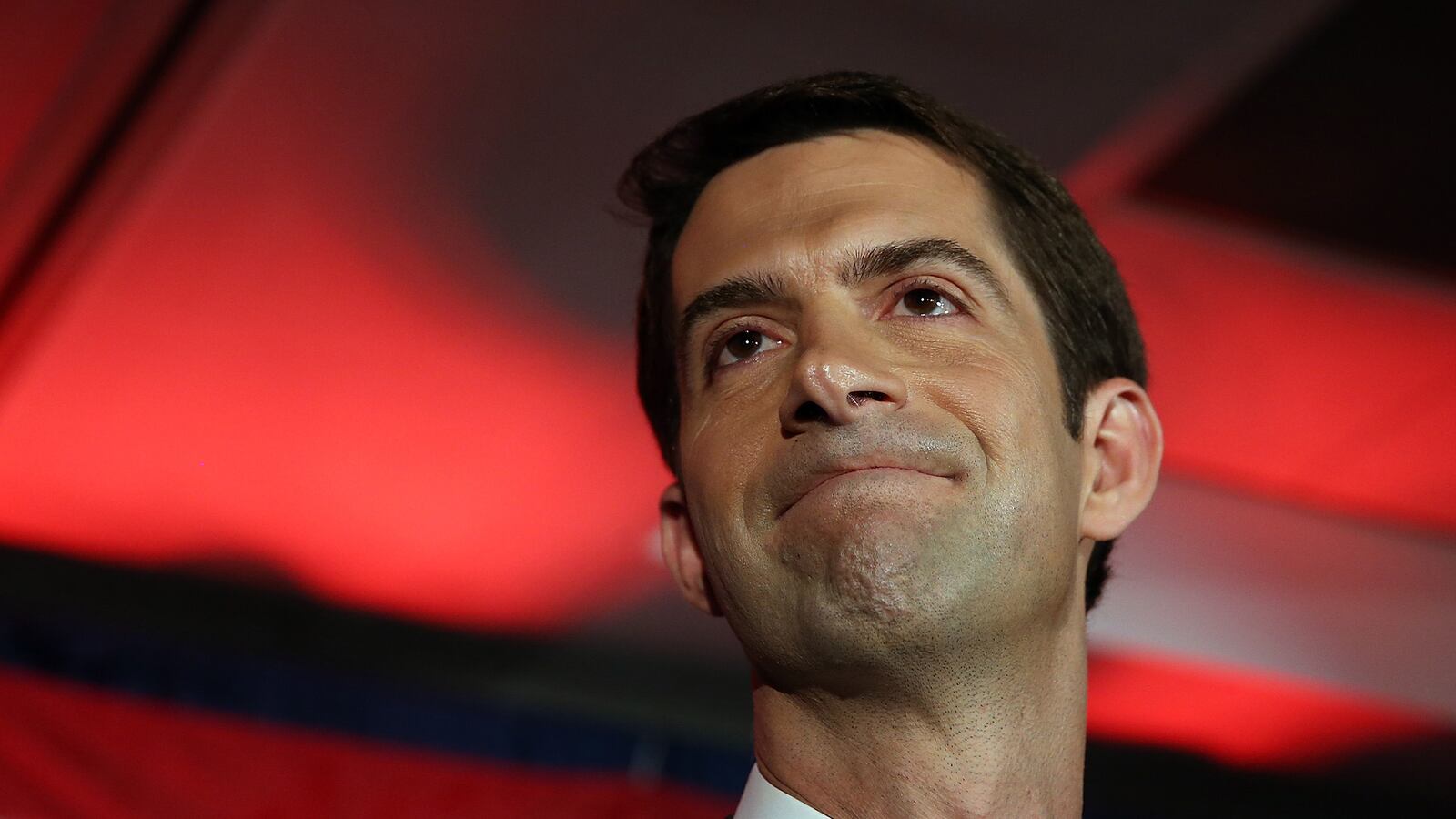

That’s what Republican Sen. Tom Cotton, a rising star in the GOP, has done and in a few weeks he’ll have successfully killed the much-needed and long overdue reauthorization of the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act of 1974. The law, which expired in 2007, banned states receiving federal money from jailing juveniles in correctional facilities where they would be in contact with adults convicted of criminal charges.

The law hasn’t been reauthorized since 2002, when George W. Bush was in the White House.

While many conservatives have joined with Democrats to embrace sentencing reform and other efforts to reduce a record prison population, Cotton is on a different path. He rails against the “criminal leniency movement,” and says he has nothing but “contempt” for those who want more “empathy” for criminals. He quotes Hillary Clinton’s comment from the ’90s about “superpredators,” for which she has apologized, saying she got it right.

“We’ve enjoyed 25 years of declining crime, which has allowed people to indulge in their wooly headed theories,” he said in a recent speech at the Hudson Institute, a conservative think tank, where he pronounced criminal-justice reform “dead” in this Congress.

His objection to the juvenile justice bill centers on its elimination of the Valid Court Order (VCO) that allows judges to lock up juveniles for “status offenses,” transgressions like running away from home, disobeying parents, underage tobacco use, or curfew violations, behaviors that would never land an adult in jail.

Greater knowledge about the science of the adolescent and teenage brain, together with data that shows incarceration doesn’t work, have led 24 states to phase out VCOs. Another 11 have it on the books, but don’t use it.

Cotton’s home state, Arkansas, has the fastest growing prison population in the country, and it is one of the most prolific users of VCOs, locking up children as young as eight for these status offenses. The state doesn’t separate juveniles according to their level of offense so kids detained for chronic truancy can be kept with someone charged with a serious crime.

“His state is among the top ten of the least safe juvenile centers in the country, with kids most likely to be assaulted,” says Naomi Smoot, a senior policy associate with the Coalition for Juvenile Justice.

When the juvenile justice reform bill first passed in 1974, one of its core protections was that status offenders not be held in confinement. In 1980, as the tough-on-crime ’80s and ’90s got underway, the “VCO exception” was added to give judges the option of jailing kids who violated a direct order from the Court, such as running away from home or refusing to attend school regularly.

Now the judges that wanted the VCO are lobbying hard for its elimination. Texas Judge Darlene Byrne, president of the National Council for Juvenile and Family Court Justice (NCJFCJ), told The Daily Beast, “Brain science has evolved, and it would be silly to think justice shouldn’t keep up with science and brain development.”

The NCJFCJ joined with over a hundred advocacy organizations, including the National District Attorneys’ Association and the Coalition for Juvenile Justice, to push for the reauthorization of the reform bill in Congress, an outpouring of support that crosses party and political lines.

The bill also has the backing of 5,000 law-enforcement agencies across the country, including dozens in Arkansas, and would have passed the U.S. Senate by unanimous voice vote this year if Cotton hadn’t stepped in with his “hold.”

Last week, the House “zeroed out” funds for juvenile justice, arguing that it made no sense to steer funds to a bill that has not been re-authorized since 2002.

“So he’s really hurting us,” says Marcy Mistrett, CEO of Campaign for Youth Justice. “This is a bill that has such extreme support, that I can’t believe it is being held up by one lone senator.”

Judiciary Chairman Charles Grassley doesn’t hide his frustration with the lone objector, noting in a recent interview that the other 99 senators have voiced no objections to Senate passage, and that if the objection is not lifted, “It could end our bipartisan effort to reauthorize JJDPA in the 114th Congress.”

Until recently a strong supporter of the VCO, Grassley now champions its removal. He told the Juvenile Justice Update newsletter that the latest research persuaded him that “locking up these young people is costly and not especially effective in reducing recidivism.”

Cotton stands alone in his opposition in Washington and in Arkansas, where a legislative task force is hard at work on prison reform, backed by Republican Governor Asa Hutchinson, a former prosecutor and Drug Enforcement Administration head in the Bush administration.

“This is not a soft-on-crime crowd,” says Bill Kopsky with the Arkansas Public Policy Panel in Little Rock. “Senator Cotton is out of touch with the reality here in the state. If we continue at the same rate (of incarceration), we will need $1.3 billion more over the next ten years than we’re currently spending, and that would require massive tax increases or cuts in everything else.”

Cotton is on the fast track in Washington. Forty years old and highly credentialed with two Harvard degrees, a coveted seat on the Armed Services, Intelligence, and Banking Committees, and multiple tours as an Army officer in Afghanistan and Iraq, “You don’t have to be a highly trained artillery officer to see a trajectory here,” enthused his introducer at the Hudson Institute last month.

The Coalition for Juvenile Justice spent two months meeting with Cotton’s staff searching for a compromise before recognizing it was hopeless.

“He’s not someone who can be persuaded,” says Naomi Smoot. “He’s looking to make a name for himself as a new law and order icon.”

With a presidential run likely in four or eight years, Cotton is betting that he can never go wrong with a hard line on crime. Juvenile Justice Reform advocates are left trying to steer around him legislatively to get a bill to the Senate floor, where they are convinced they have more than enough votes for passage.