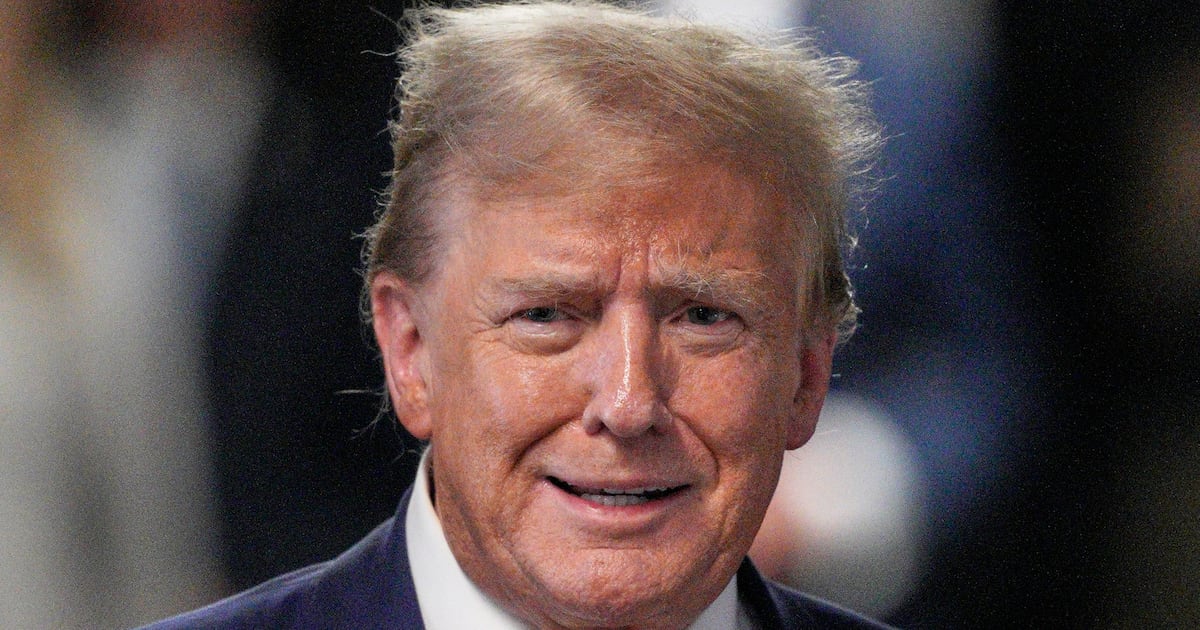

A critically inexperienced candidate, running on an “America First” platform, who isn’t supposed to be his party’s nominee, goes on to win the presidency. Moving into the White House, he begins immediately upending tradition.

As allegations of cronyism and womanizing swirl about, he sets the nation on an isolationist course while inarticulately advancing confused and often discordant policies which will build his administration’s legacy of scandal and indictment...

Err... sorry. But that’s 1921.

Comparison between the current and previous Republican presidencies is inevitable. Unavoidable, actually, as Trump continues glorifying himself in unschooled comparisons to Reagan, Eisenhower, even Lincoln. The plain truth, however, is that in his first year, he has proven closer—far closer than anyone may care to imagine—to another Republican president, the incredibly underappreciated Warren Gamaliel Harding. Step by reactionary step, campaign promise by promise and character flaw by flaw, the two are uncannily matched.

Except, by comparison to the massive legislative record Harding rolled up in just nine calendar months, Trump has dick to show.

Trump’s freshman year in office produced scant legislative result. Pronounced intentions, the border wall and health care repeal, for example, proved elusive. Yes, there were countless presidential signatures concerning regulation rollbacks—but by the measure of enacting significant legislation, Trump’s major success amounts to one Supreme Court replacement and a struggled-up Hail Mary! It’s Christmas in December tax reform bill of partisan support. Harding, in contrast, was the very model of one-party expedience and within months of his March 4 inauguration, Congress had completely remade America's immigration policy, passed historic tax reform, re-monopolized the telecommunications industry and funded a substantial national infrastructure program—all before December recess.

Harding’s Republican administration mostly refuted the progressive anti-monopoly, interventionalist policies which had arguably dominated American politics since Theodore Roosevelt. In May, for example, Harding signed the Johnson Quota Act (The Emergency Immigration Act of 1921) which was, in effect, the most significant piece of immigration legislation in U.S. history to date. Johnson redefined America's immigration policy, formally establishing quotas on historic immigration patterns. Largely limiting entry to 3 percent of any nation’s resident U.S. population (as established in the 1910 census) Johnson favored immigration patterns from European nations and as a result, in the following year, U.S. immigration fell approximately 60 percent to slightly over 300,000 entries.

In 1924, the Republican-led Congress tightened these draconian limits even further, establishing a 2 percent limit on an even older census.

As far as huge tax cuts meant to spur economic expansion, Harding was the original poster boy. Dramatically reducing taxes on higher income brackets, the Revenue Act of November 1921 also established a 10 percent percent rate on net corporate income and provided preferential treatment to capital gains. These substantial “reforms” did not, in fact, go as far as then Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon had proposed. Eight years later, still secretary of the Treasury, serving his third consecutive Republican president, Mellon presided over the Wall Street crash of 1929. As consistency had become a Republican trait, Mellon remained in charge of the Treasury until February 1932, when—threatened with congressional impeachment—he accepted appointment as ambassador to Great Britain.

In terms of infrastructure, unlike many, Harding effectively achieved innovative infrastructure legislation in his first year. The National Highway or The Phipps Act, signed in November 1921, established the groundwork for a national highway system, creating the initial gridwork for roads and bridges still in use today.

Concerning effect upon the judiciary, Trump and Harding are at a technical draw over major judicial appointments. The advantage however would have to go to Harding whose nomination of former President Taft as Chief Justice in Spring, 1921, arguably trumps Trump’s naming of Neil Gorsuch as an Associate. Similarly, Trump has a high hill to climb to even approach Harding’s accomplishment of four Supreme Court appointments in a single term. Doubly impressive, if you consider that Harding survived in office just 29 months.

Where Trump and Harding seem irreparably twinned is their respective lack of qualification for higher public office, their somewhat darker personality traits, and perhaps most sadly, their shared inability to articulate themselves.

Neither was supposed to capture their party’s nomination. Trump beat a field of known challengers with an unorthodox axe-handle-like bullying style. Harding, a first-term Ohio senator, was a machine candidate, famously emerged from a “smoke-filled room” at a deadlocked convention. Harding finally secured the nomination on the tenth round.

In the words of Ohio boss turned campaign manager turned Harding’s U.S. Attorney General Harry M. Daughtery, he “looked presidential.”

Both Harding and Trump’s appeal was undeniably populist. The 1920 election was historic. Harding first pledged the idea of “a return to normalcy” at a Boston campaign rally in May, 1920. (Equally unproven in national politics, Trump rode an escalating promises to “Make America Great Again” before notably reviving Harding’s original campaign slogan of “America First.”) While argument persists whether “normalcy” is correct usage (as opposed to “normality”) it reverberation has done little since to enhance Harding's reputation as a public speaker. In an era before radio, talkies and Tweets, we know Harding sounded presidential from wax cylinder recordings, possessing a deep stentorian voice and a polished oratory style. By general agreement—including his own—he had precious little to say of any real consequence. Harding himself called his use of regional colloquial, the practice of “bloviation.” A stump style of speech-making he described “the art of speaking for as long as the occasion warrants, and saying nothing.”

Grown before microphones and public address systems, it was the style which fired up evangelical campgrounds and inspired assemblies under canvas tents—a style which Harding first developed as a Chautauqua speaker, beginning in 1908 when he first supplemented his salary as Ohio’s Lt Governor, lecturing on Alexander Hamilton. Effectively impressive to the throng, it drove his opponents and critics batshit crazy. Democrat William Gibbs McAdoo, Wilson’s Treasury Secretary (and son-in-law)—hoping to run for the presidency—decried it a “big bowwow style of speaking.”

Indeed, the most often-cited summarization of Harding’s speaking ability (which has appeared on the White House’s own website since George W. Bush) remains McAdoo’s description of “an army of pompous sounding phrases moving across the landscape in search of an idea.” (The phrase concludes: “sometimes these meandering words would actually capture a straggling thought and bear it triumphantly as a prisoner in their midst, until it died of servitude and overwork.”)

No less a writer than H.L. Mencken made Harding a franchise. Regularly aghast at Harding’s pronouncements, which he dubbed “Gamaliese,” Mencken was responsible for a quote which has been in great revival these past 13 months. “On some great and glorious day,” he wrote in the Baltimore Evening Sun on July 26, 1920, ”the plain folks of the land will reach their heart’s desire at last, and the White House will be adorned by a downright moron.”

The first presidential election after the World War, the 1920 election was a bellwether. Hallmarked as the first in which the 19th Amendment, allowing women the vote, went into nation-wide effect, it was also held under the imminent arrival of Prohibition. Harding fought the election largely from his Ohio front porch—a revival of McKinley’s campaign style—where silent cameras recorded his image. On occasion, enthusiastic crowds of supporters were brought in by trains to hear him speak at a local stadium.

On Election Day, having outspent Democrats by four-to-one, Harding took office with over 60 percent of the popular vote. An unprecedented mark and one achieved since by only Roosevelt, Johnson, and Nixon.

Morality plagued both candidates. Twice-divorced in tabloid headline circumstance, Trump continues to heatedly deny allegations of sexual harassment and scabrous behavior prior to his election, even as victims, witnesses, and enablers parade steadily forward.

Again though the advantage clearly goes to Harding, who somehow managed to conduct a long-term affair with one mistress while fathering a daughter with another woman at the same time and while in the White House, and somehow managing to keep everything concealed until, as the White House website concedes, “the summer of 1923 when he died unexpectedly in California, shortly before the public learned of the major scandals facing his administration.”

A death, many historians entertain was a poisoning by his extremely pissed-off and “I’ve had just about enough of this” wife.