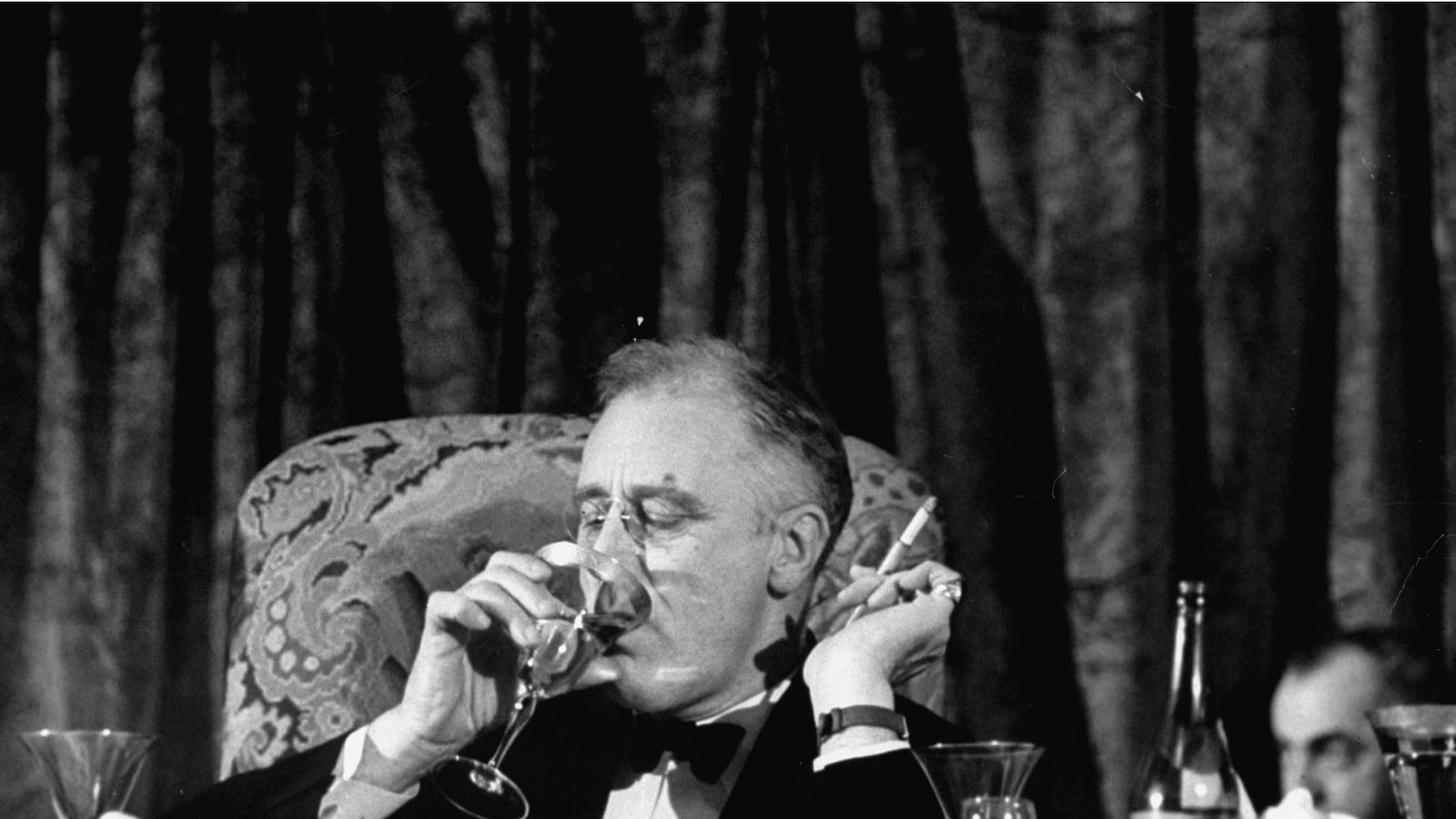

Given that the country was in the throes of the Great Depression and World War II was on the horizon, no one could blame President Franklin Delano Roosevelt for wanting a stiff drink.

In fact, dating back to at least his days as governor of New York, on most nights before dinner, FDR would host a cocktail hour for friends and associates.

For such occasions, he had a sterling silver cocktail shaker with a bamboo motif and six matching cups. (He even had a maroon leather case with a blue velvet interior for the set so he could take it with him when he traveled.)

“The President made quite a ceremony out of this daily cocktail hour, mixing the drinks himself from various ingredients brought to his desk on a large tray,” wrote Samuel I. Rosenman in his 1952 book, Working with Roosevelt.

“The President, without bothering to measure, would add one ingredient after another to his cocktails. To my unpracticed eye he seemed to experiment on each occasion with a different percentage of vermouth, gin and fruit juice. At times he varied it with rum—especially rum from the Virgin Islands.”

One of his infamous concoctions was mixing gin with herbal liqueur Bénédictine. (I don’t suggest trying to making that one at home.)

Generally he stuck to fixing martinis and old fashioneds. But even when it came to martinis he seemed to be constantly tinkering.

Grace Tully, his personal secretary, stated in her 1949 book, FDR, My Boss, Roosevelt liked three parts of gin to one part vermouth.

But the recipe for the FDR Special in The Val-Kill Cook Book, which contains family recipes and was edited by his granddaughter, Eleanor Roosevelt Seagraves, calls for two parts gin and one part dry vermouth. (Curiously, it also calls for the ingredients to be shaken with crushed ice and not stirred, which was the norm before James Bond decided otherwise.)

In addition, he occasionally introduced absinthe to the mix and had Pernod Absinthe in his White House stash.

Despite his fancy bartending set and his dedication to and enthusiasm for the craft “the drinks were notoriously bad,” says William Harris, deputy director at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park.

At his famous meeting with Joseph Stalin at Tehran he made drinks, and Stalin supposedly commented that it was “cold on the stomach.”

It was hardly a ringing endorsement for the president’s bartending skills.

Usually, FDR didn’t like to mix business with pleasure. Doris Kearns Goodwin described the jovial atmosphere in his nightly get-to-together in her Pulitzer-Prize winning book No Ordinary Time: “During the cocktail hour, no more was said of politics or war; instead the conversation turned to subjects of lighter weight—to gossip, funny stories and reminiscences.”

FDR, like Harry Truman, was more of an enthusiast than a huge imbiber.

“The President liked to drink, but seldom drank much,” wrote John Gunther in his 1950 tome Roosevelt In Retrospect. “Generally he had two cocktails, not more. They were fairly stiff.”

However, Gunther also tells the legend that FDR might have had gins of different quality “one for favored guests, one for the less favored.” He unfortunately doesn’t reveal who was on either list.

Even during Prohibition, according to Geoffrey Ward and Ken Burns The Roosevelts: An Intimate History, FDR had stocks of gin, rum, and scotch in a closet of his New York home and also at his retreat, Warm Springs, in Georgia.

His thirst for alcohol was at odds with wife, Eleanor, who didn’t drink and didn’t take part in his happy hours. It was understandable since her father and brother had battled alcohol addiction. “She’d seen up close and personal the impact of alcohol on her family,” says Harris.

Despite Eleanor’s views, FDR was a staunch supporter of repealing Prohibition. So much so, that while the Constitutional amendment to repeal Prohibition was being ratified, FDR made sure Americans wouldn’t go thirsty by legalizing the manufacture and sale of beer and wine that was 3.2 percent alcohol or less. (This past Tuesday was, in fact, the 83rd anniversary of the signing of this act.)

In a note to Congress urging them to pass this legislation he ended his note by saying, “I deem action at this time to be of the highest importance.” We couldn’t agree with him more.