Late in the afternoon of Dec. 5, 2007, the reception room in the National Archives Building on Pennsylvania Avenue was full and noisy. Maryellen Trautman wasn’t wearing her hearing aid, and she was having trouble making out what some at the holiday party were saying. As the host, Archivist of the United States Allen Weinstein, began his brief introductory remarks, Trautman sat down on a loveseat by herself. She wasn’t shy, she was just better in smaller groups.

When Weinstein walked toward her and said something, she wasn’t sure at first that he was addressing her. Weinstein, a diminutive, controversial historian of 70, spoke softly, attributed at the time to his Parkinson’s disease and his unassuming manner. He sat down next to her, still saying something that Trautman, a 64-year-old National Archives employee, couldn’t quite hear. She leaned closer.

“You’re the most beautiful woman in the room,” Weinstein seemed to whisper.

Trautman was certain she couldn’t have heard him correctly. “What?” she asked.

Weinstein invited her to talk in the hallway.

The Archives’ suite of high-level offices, known as Mahogany Row, is located along a hallway with reflective surfaces that make it even more difficult to talk, particularly when filled with guests spilling out of a reception. Weinstein’s faint words were bouncing around.

“Let’s go to my office,” he suggested.

Weinstein let her in and, without Trautman seeing, locked the door behind them. They were alone.

During the next few minutes, Allen Weinstein would sexually assault Maryellen Trautman. Federal investigators would later substantiate that Weinstein, the chief official overseeing the federal government’s most important documents, had created a “hostile working environment by having verbal and physical conduct of a sexual nature for multiple female employees.”

Weinstein, who died in 2015, claimed that his behavior was the result of medication for his recently diagnosed Parkinson’s disease. His family now says that he was later diagnosed with a form of dementia.

“Parkinson’s disease dementia is a terrible disease that crippled our father in his last years of life and turned him into a different person before he died,” Weinstein’s sons, Andrew and David, told The Daily Beast. “We would like to offer our deep apologies to anyone he treated inappropriately, either during the disease or before it.”

But medical experts found both these explanations dubious. And even though investigators documented a disturbing pattern of behavior going back more than a year, Weinstein appeared to use his position of authority and close political connections to escape responsibility.

Weinstein ultimately faced no charges, nor was any public notice made of his misconduct. Instead, a little more than a year after the holiday party, the George W. Bush White House permitted him to quietly resign. He then moved on to a major university, where he would sexually assault again.

Over the past few months, women in the worlds of entertainment, media, and politics have exposed prominent men who have committed sexual assault. Their allegations have upended industries and sparked society-wide introspection about workplace cultures.

But while perpetrators of sexual harassment are often in positions of power, they are not always household names. That’s certainly true in government.

An upcoming report by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board, Sexual Harassment Trends in the Federal Workplace, will show that while sexual harassment behaviors occur less frequently than they did two decades ago, 18 percent of female federal employees reported experiencing them over the past two years. According to the report, 1 percent of the federal workforce reported experiencing actual or attempted rape or sexual assault.

One percent of federal employees is around 21,000 workers.

Trautman was one of those 21,000.

Trautman is well known among librarians and archivists. The American Library Association has described her as “an activist documents librarian” and “a true life-long champion of government information.”

She worked in the library at Archives II, the large facility in College Park, Maryland. Attending the December holiday party brought her to Archives I, the National Archives Building. Though Weinstein had led the agency for almost three years, Trautman had yet to meet him. She felt complimented to have the chance to speak with him, even for a brief moment during a social event.

The account of what happened next has never been made public. It is the product of contemporaneous investigations and interviews over the past several years with Trautman, dozens of other principals and experts, and more than 250 pages of official documents released in response to public-records requests.

Once inside Weinstein’s office, Weinstein took Trautman by the arm and led her to the window, dramatically pushing back the curtain and declaring it, “The loveliest view in the city!”

Looking into her eyes, he added, “But no more beautiful than you.”

Trautman politely tried to change the subject, telling Weinstein about changes to that view over the years.

He said he’d noticed her on the loveseat in the reception room while he’d been speaking. Placing his hands on her shoulders, he told her, “You are the most beautiful young woman in the room, and I would like to get to you know you.”

Trautman nervously thanked him, stepped back, and suggested that his glasses be checked.

She had been happily married for 30 years. Weinstein’s advance was not just unwelcome, it was bewildering.

He pulled her closer and asked for a kiss. She was stunned.

She offered her hand instead. But Weinstein kissed her on the cheek, his “whiskers” brushing her face as she turned away. He told her he wanted more than that, then forcefully kissed her mouth.

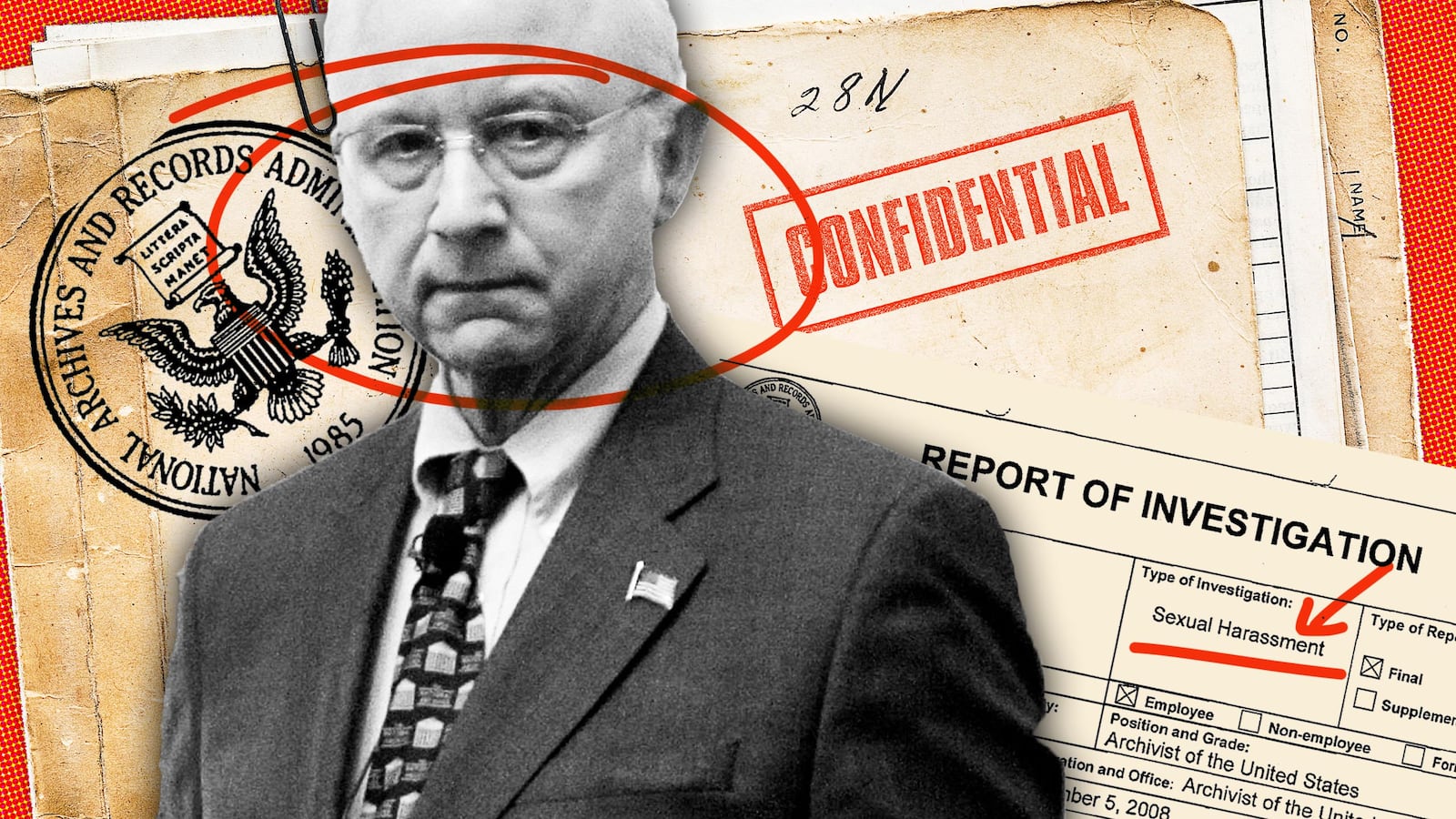

Maryellen Trautman told investigators she was assaulted by Weinstein at the Archives.

Photo Illustration by The Daily Beast/Chas DownsTrautman tried to step back further, but couldn’t. He then led her by the shoulders, more insistently this time, into his private bathroom. He positioned Trautman in front of the mirror, and, standing behind her, caressed her. She froze.

“What do you see?” he asked her.

She didn’t know what to say. “I… see… me,” she answered.

Moving his hands over her, he said, “I see the most beau...” There was a knock on the door.

Weinstein left the bathroom and went to open the door to the office. Trautman took that opportunity to get out of the bathroom and retrieve her purse, which she had left on a table when she entered. Recounting the assault in 2016, she said she doesn’t know why she didn’t leave his office in that moment. “It was so unexpected,” she said, “and it happened so fast."

A staff member gave Weinstein a message and he quickly shut the door. This time, Trautman saw him lock it.

Then the phone rang. Weinstein answered, curtly saying, “Not now,” and hung up.

He went to a pantry, returning with two glasses of red wine, offering her one. “It tasted cheap,” Trautman recalled. “It was cheap red wine.”

They sat in his office, he on a chair next to the table and she on a chair next to the door, drinking the cheap red wine. Weinstein asked Trautman about her position at the National Archives.

While she wanted nothing more than to leave the room, Trautman thought that making job-related small talk was preferable to what Weinstein had been doing. She replied that she had 40 years of experience as a government publications librarian, had won awards for her work, but had remained as a GS-12 for many years.

Weinstein suggested they go for coffee sometime.

Still trying to politely make clear she had no interest in Weinstein, Trautman told him she didn’t work in Archives I, but out at Archives II in College Park. He expressed disappointment, as he seldom went to Archives II. He told her to send him a résumé and he would “see what he could do.”

There was another knock, and when Weinstein got up and unlocked the door to answer it, Trautman used the opportunity to excuse herself. In her written statement, she said she “thanked him for the wine and conversation and disappeared down the hall” to her waiting husband, Darrell Lemke, who noticed her departure from the reception and had gone looking for her. Trautman told him about what had happened on the Metro ride home. He listened in silence.

“As soon as Maryellen appeared, she gave me a brief summary of what had happened,” said Lemke. “She was clearly upset by Weinstein’s advances. I was relieved that that she was otherwise all right but likewise disturbed by his unacceptable behavior.”

Trautman did not send Weinstein her résumé immediately. It would be nine weeks before she hand-delivered him a copy in that same office, while wearing a wire.

The morning after the assault, Trautman called her colleague Bernadine Abbott Hoduski, another recognized advocate of access to government publications, who worked for the Joint Committee on Printing.

“I’ve believed her since she told me about it the day after it happened,” Hoduski said in a 2016 interview recalling that conversation. “I would stake my entire reputation on it.”

That same day after the party, Trautman also called Sam Anthony, her former colleague in the Library who then worked directly for the Archivist (Anthony told investigators that the first call he received from Trautman didn’t come until six weeks later, though Trautman said she is certain it was the day after the assault). In an interview for this article, she said she briefly told Anthony what Weinstein did to her, and asked, “Who are the others he did this to?” She said that Anthony stammered, told her he didn’t know what she was talking about, and hung up.

Anthony did not respond to an interview request.

Trautman then requested help from her senator, Barbara Mikulski (D-MD). Trautman told investigators that a Mikulski staffer advised her not to report Weinstein, that since she “only had a few more years to work, getting involved in this would be more trouble than it was worth unless others speak up.” Mikulski, who retired in 2017, did not respond to a request for comment. A former senior staffer for Mikulski, who is not authorized to speak on the record, wrote in an email, “The senator’s office would contact the federal agency when the constituent asked them to. Sometimes there were unintended consequences. They left it to the constituent whether to pursue the matter or not.”

In the days following the assault, Trautman grew more angry. The manner in which Weinstein had assaulted her—smooth, confident, practiced—made her certain he’d done this to other women and would do it again.

“And,” she remembers thinking, “I’m 64! A married 70-year-old man does not, all of sudden, just pick a woman of my age to begin doing something like this.”

She didn’t know how to proceed. Veteran Archives employees knew that in the too-recent past, whistleblowers were punished even for identifying problems within the agency.

Complicating matters was that, at that time, the National Archives was desperate to avoid another public-relations fiasco. The agency was reeling from the 2006 revelations that it had entered into secret agreements with the CIA and the Air Force to reclassify previously open records. It was still defending its 2003 mishandling of former Clinton National Security Adviser Sandy Berger’s theft of classified documents (and the “sting operation” against him that some Archives officials conducted on their own).

The public was just beginning to learn of the failure of the Electronic Records Archive, which reportedly ended up costing more than $560 million. An audit of the artifact collections at presidential libraries showed a “near-universal” security breakdown, particularly at the Reagan Library, where officials could not account for 80,000 items. Then came the disclosure that 22 million Bush White House emails were missing and likely lost. To say that in 2008 the National Archives was extremely defensive of its reputation would be an understatement.

On Jan. 23, 2008, seven weeks after the assault, Trautman called Sam Anthony again, demanding to learn if he knew anything about Weinstein’s behavior. Again, Trautman says, Anthony claimed that he did not, promised to get back to her, and hung up.

According to one witness account in the investigation records, when Anthony told colleagues about the call immediately afterward, he was “white as a ghost.” An Archives official instructed Anthony to make a written statement about what Trautman had said. In it, Anthony wrote, “At this point, I do not believe she called to warn me of impending lawsuits or the like, but to see if this was a recurring problem with the Archivist, in hopes I or someone else could keep this from happening again.”

The records show that an Archives official and Anthony contacted Deputy Archivist Adrienne Thomas, who brought Anthony’s report to the National Archives general counsel, Gary M. Stern, that afternoon.

When reached for comment, the then-National Archives inspector general, Paul Brachfeld, said that agency procedure was to report such incidents to his office.

According to the records, however, over the next six days, Stern and his colleague, Designated Agency Ethics Official Christopher M. Runkel, first contacted several other federal organizations, including the Equal Opportunity Employment Commission, the Department of Justice, and the White House Counsel, for advice on how to proceed.

In a second written statement, Anthony detailed a follow-up phone call he made to Trautman on Jan. 25. “I asked her how she would like me to proceed with what she’s told me. Four times she asked me to ‘find the other women.’”

On Jan. 28, Stern suggested that someone in the agency advise Trautman of her rights and how to receive counseling. He then reached out to the White House, which had administrative authority over Weinstein. Whomever Stern spoke with at the White House told him that the National Archives “needed to follow agency policy on fact finding or an investigation” and instructed him to provide that information to the White House counsel.

Almost a week after Anthony’s report of Trautman’s call, Stern, Runkel, and Thomas finally contacted the Office of Inspector General, to meet with Brachfeld.

Stern and Deputy Archivist Debra S. Wall, then Weinstein’s chief of staff, declined to be interviewed; Thomas, now retired, could not be reached for comment. A spokesperson for the Archives, however, noted, among other things, “When informed of the harassment, [National Archives] officials promptly reported it to the White House, the [National Archives] Office of Inspector General, and other appropriate agencies. The OIG and FBI were then responsible for investigating this matter.” Because of the legal sensitivity of the matter, the spokesperson added, “very few NARA officials were informed of the investigation or its findings.”

Contemporaneous notes show that not everyone was pleased with how the allegations were handled. An entry from Brachfeld’s daily log for Jan. 29, 2008, indicates that Stern and Runkel met with him that day, and then adds the following:

<p><em>Gary not learning from the [Sandy] Berger matter once again went external in lieu of coming to the OIG and contacted OGE, WH OA, EEOC, DOJ, etc. Then he came to the OIG. When they began to speak in a cryptic manner about the alleged events I asked for specificity… </em></p>

Brachfeld and his staff immediately brought in the FBI. William Welch II, the chief of the DOJ’s Public Integrity Section, confirmed to the FBI’s Washington Field Office that he would prosecute the case “if sufficient evidence is developed.”

The Office of Inspector General began interviewing National Archives staff. Their findings were exhaustive. When investigators spoke with Sam Anthony on Jan. 30, he told them Weinstein “had not displayed inappropriate behavior in his presence,” but that he had “seen women meet privately with Weinstein in Weinstein’s office.”

He also told them that the day after Weinstein assaulted Trautman, he had been asked to “look into how a GS-12 employee could automatically become a GS-13 for Weinstein.” Anthony noted that “the request was unusual.” He did not take it seriously, and Weinstein did not follow up.

An Archives official would reveal to investigators a more disturbing truth: There were other women. Some within the agency had noticed Weinstein’s inappropriate behavior for at least 16 months before he assaulted Trautman.

The official, whose name was redacted, told investigators that she “first became aware of the possibility of inappropriate behavior” by Weinstein in August 2006.

The official told investigators that, while she had no direct knowledge, there were rumors that Weinstein was “hitting on” a National Archives employee and heard “through the grapevine” that he was “acting inappropriately during his trips.”

The employee then recounted an incident from a year earlier when she and Weinstein had dinner across the street from the Archives Building. While at the bar, Weinstein leaned in to talk to her and put his arm around her shoulders and the chair. “[She] thought it was a friendly gesture but also thought this was a ‘stupid’ action on the part of [her] supervisor. [She] broke away from Weinstein by physically moving [her] body around.”

She also told investigators that another woman told her Weinstein had read her poetry behind closed doors and once hugged her, but that “she did not want this information to go anywhere.”

According to the report, there was talk of “setting-up sexual-harassment training for Weinstein before the call was received from Trautman.” The report also noted that interviewees acknowledged it had been many years since they themselves had received sexual-harassment training at the Archives.

The official told investigators so much information that about halfway through, they informed her she was not required to speak with investigators and had the right to be represented by counsel. The interview continued.

“In the last six months, [she] has noticed an increase in young women being alone with Weinstein, in his office, at the end of the day,” the investigators noted. “[She] has been trying to evaluate what type of women Weinstein has in his office or is inviting out. They seem to be ones that would be impressed and see glamour in being with the head of the agency.”

Within just a few weeks of launching the investigation, the OIG determined the allegations against Weinstein were “substantiated.”

On Feb. 27, 2008, special agents interviewed Weinstein for the first time. Weinstein told them that he wanted to speak with them, but did not wish to proceed without his attorney present.

On March 11, Weinstein’s lawyers told investigators that Trautman had visited Weinstein in his office and “tried to get close to him”—and that Weinstein had felt he was being recorded. They said he denied kissing Trautman.

Investigators did not hear anything for months. Finally, on June 30, Weinstein’s lawyer informed the Public Integrity Section that Weinstein was “considering resigning.” They even set a date for the resignation—Dec. 4.

But Weinstein resisted leaving, offering investigators, through his attorney, a variety of reasons why he should remain, chief among them the need for “continuity” in leadership at the Archives. Weinstein inferred that a deputy of his was under investigation (there is no publicly available information to support this claim) and also said that another individual who was available to assume leadership of the agency “had health concerns.”

Later that summer, Weinstein’s attorneys dropped the push to keep Weinstein on the job. But in an effort to avoid a potential prosecution, they provided the explanation that his medication was to blame for his behavior.

<p><em>During discussions between Weinstein’s defense counsel and the Department of Justice, Public Integrity Section, Weinstein admitted to initiating unwanted harassing behavior toward the victims. In Weinstein’s defense, he had recently been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, and has been taking medicine to counteract the disease’s progression. Weinstein alleges that the medication caused him to become ‘hyper sexual,’ which explained his behavior.</em></p>

Weinstein’s financial backer and close personal friend, Peter Kelly, who said he was unaware of Weinstein’s misconduct until being informed for this article, also claimed that many who are treated with L-DOPA experience hypersexuality. “Well, you know that’s how it is with Parkinson’s patients,” Kelly said. “We went through the same thing with my brother. Thirty years, I know a lot about Parkinson’s and it happens all the time.”

The medication Weinstein was prescribed is not identified in the records. According to the medical literature, about 3.5 percent of patients who are treated with dopamine agonists report impulse-control problems. These can include excessive spending, gambling, and a “marked interest increase in sexual interest, arousal, and behavior.”

However, Timothy W. Fong, a clinical professor of psychiatry at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior at the University of California, Los Angeles, cautioned against holding these medications as solely responsible. “In rare cases,” Fong said, “these medications have been associated with triggering compulsive behaviors. But if you have never gambled before, it is not likely that a dopamine agonist will suddenly turn you into a problem gambler.” As to whether impulse-control problems caused by these drugs can lead to sexual assault, Fong said, “I have never heard of treatment for Parkinson’s disease causing someone to commit criminal sexual misconduct.”

On Dec. 4, 2008, several weeks before Bush’s second term ended, Weinstein announced his resignation, effective in two weeks. He immediately became a visiting professor at the University of Maryland College of Information Studies, from which, 18 months later, he was fired after university officials learned that he had sexually assaulted at least one student there.

A university appointment made sense on the surface. Weinstein’s professional roots, after all, were in academia.

He was a history professor at Smith College when, in 1969, at the age of 32, he married one of his undergraduate students, a senior named Diane Gilbert. Weinstein left Smith in 1981 and spent a short time at Georgetown University while working for the Center for Strategic Studies and the editorial page of The Washington Post. In January 1984, he assumed the presidency of the Robert Maynard Hutchins Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions at the University of California at Santa Barbara. After only eight months on the job, the board abruptly fired him, declining at the time to comment on the reason.

Soon after, Weinstein found a soft landing at Boston University, only to exit four years later. “You know, no one ever knew [why he left],” said Thomas Glick, who was History Department chairman. “One day, Allen was just gone.”

After leaving Boston University, Weinstein and Diane divorced.

By then, Weinstein had established his own think tank, the Center for Democracy. Early and longtime backers included the political consulting firm Black, Manafort, Stone, and Kelly. Two of the four name partners, lobbyist Paul Manafort, and self-described “money guy” Peter Kelly, sat on the center’s board and provided funding.

The center’s work brought Weinstein into contact with leading figures in international affairs, including two-time chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Dick Lugar (R-IN). “I got to know Allen Weinstein because his Center for Democracy was publishing good information,” Lugar said. “When President Reagan asked me to monitor elections in the Philippines, I asked Allen to assist. We subsequently remained close, and I recall fondly our considerable association over the years.”

Lugar said that the first time he ever heard about the allegations of sexual assault involving Weinstein was when he was told of them during an interview for this article. “I’m very sorry to hear that,” he responded.

Having established himself as a prominent voice on foreign affairs, Weinstein continued to rise. In 1986, he was awarded the United Nations Peace Medal for his efforts to “promote peace, dialogue, and free elections in several critical parts of the world.” He was the first American whom Boris Yeltsin’s staff contacted during the attempted Russian coup in 1991. In the 1990s, he chaired election-monitoring delegations to Russia, Nicaragua, and El Salvador.

Allen Weinstein pontificating in his office.

Dirck HalsteadHe also became a lightning rod for controversy, most prominently over his claims that State Department official Alger Hiss was a Soviet spy. While many on both sides of the aisle accepted Weinstein’s conclusion, critics charged that he mischaracterized evidence, misquoted interview subjects, and paid for exclusive access to former Soviet archival records he then refused to share.

In 2004, George W. Bush nominated him to run the Archives, which serves as the protector of the United States’ most important documents, employs a staff of around 3,000 at facilities nationwide (including 13 presidential libraries), and handles tens of thousands of Freedom of Information Act requests each year for some of the nation’s most sensitive materials.

It was a divisive choice, in part because Bush, without consulting outside stakeholders or notifying Congress, had forced out the sitting Archivist (a non-term-limited position) and named Weinstein as his successor. Moreover, the presidential papers of George H.W. Bush, the sitting president’s father, were set to become public soon, and George W. Bush was attempting to reverse the Presidential Records Act—which, among other provisions, allowed outgoing presidents to withhold certain kinds of records for up to 12 years.

Weinstein, who had assured the administration that he would support its view of the PRA, was seen by many as a yes-man.

Initially, his nomination did not clear the Senate, reportedly after an anonymous senator placed a “hold” on it. But in 2005, a few days after Bush’s second inauguration, he resubmitted Weinstein’s name, and the Senate approved Weinstein by voice vote.

At his swearing-in, Weinstein offered a “personal pledge” to “do everything I can to assure for all employees the most attractive working conditions possible in supporting NARA’s uniquely talented band of archival brothers and sisters.”

Allen Weinstein, then heading the National Archives and Records Administration, waiting to testify at a House Oversight Committee and Government Reform

Tom WilliamsFive days after the OIG began its investigation, Maryellen Trautman went to Allen Weinstein’s office carrying a special purse containing audio and video equipment that transmitted the encounter to nearby agents, but was later found to have failed to record. This account is based on a written statement made the following day by the agents, who also interviewed Trautman two days after the visit and included a memorandum of that interview in the record.

After 5 p.m., Trautman entered the office and greeted Weinstein as “Allen.” As Trautman moved around, the device broadcast intermittent static.

Weinstein told her he was collecting things to leave for a dinner in five minutes, and invited her to sit. She remained standing.

She asked Weinstein if he remembered her, and he told her that he did. She told him she was there to give him her résumé, as he had asked her to do.

She asked him if he remembered being at the window when they last met, and he said, “Yes.”

She said she had been confused about their last meeting. Weinstein asked her if she had spoken to anyone else about it and she told him that she was too embarrassed to tell anyone.

He told her that she was an attractive woman. She responded that she was not used to hearing that. She asked if he remembered kissing her cheek.

Weinstein responded that he recalled kissing her cheek.

She asked if he remembered kissing her lips.

Weinstein responded that he recalled kissing her lips. He then told her he wanted another kiss.

She asked if he kissed other women. He said he didn’t make it a practice and that he hoped he wasn’t too forward, but that she was special and attractive and he couldn’t help himself.

But, he told her, it was consensual.

Years later, Trautman recalled that it was at this point she began to think that Weinstein suspected he was being recorded. His entire demeanor changed and his conversation turned businesslike.

He invited her to sit down and brought her over to the area with chairs and a couch. He sat in a chair. She reminded him that she had some difficulty hearing, and sat adjacent to him.

Trautman commented that he didn’t offer her wine as he did at their last meeting. He said he hadn’t opened it yet. She told him her throat was dry. He went to the pantry and returned with a glass of water for her.

She handed him her résumé and he looked it over. He said he could tell she had good qualifications and had been treated poorly in the past.

Trautman said that at their last meeting, he told her he “wanted more.” She asked him what he’d meant. She asked, if she had kissed him would that mean she would have been promoted to a GS-13 position?

He said that he did not like to mix business with pleasure but that he wanted to help her.

He got up and opened the door wider. He said he had to leave to attend his dinner, but that he wanted to chat again. He would call her.

A staff member came into the room.

The agents heard sounds as if Trautman and Weinstein were moving around.

Weinstein walked Trautman out of the office and into the hallway. He told her he hadn’t meant to offend her and would have to apologize for his behavior.

But, he repeated, it was consensual.

Trautman left the office at approximately 5:22 p.m.

Over the course of several weeks in January and February 2008, the OIG discovered at least five other women whom Weinstein sexually assaulted, sexually harassed, or both. Other than Maryellen Trautman’s, the government redacted the names of those who were interviewed.

One woman, who worked for the private foundation that supports the agency, told investigators she understood that if Weinstein gave her a position in the Archives, she would be expected to maintain an intimate relationship with him.

She said that Weinstein made her uncomfortable by touching her without asking her while on a business trip, and inviting her to his office for wine and to read her romantic poetry. According to the OIG investigation, “She said that... on many occasions Weinstein would place his hand on her hand or close to her leg. While seated in his office, she would place a cushion between her and Weinstein to create space.”

The woman said Weinstein would hug her after he walked her out of his office and kiss her on the cheek.

She would arrange to have co-workers interrupt her meetings with him if they lasted more than 15 minutes. Once, he told her he knew she was being “rescued.”

Another woman told investigators that Weinstein appeared to change her work responsibilities without going through her supervisor because, she felt, he had an inappropriate personal interest in her. He once arranged to have her give him a ride to his car. But then he asked her to bring him to her house, and he would call a cab from there. Instead, she drove him to his house. When they arrived, he asked for a kiss. Shocked, she didn’t answer. He leaned over and kissed her on the cheek.

Weinstein repeatedly invited her to have drinks with him, in his office or at a restaurant. She said that she was “very uncomfortable but because Weinstein was the head of the agency it was very difficult for her to tell him she did not want this type of contact.”

Another woman told investigators that Weinstein invited her to his office to read poetry to her while they were alone, with the door closed. He began to ask her out for drinks, dinner, or coffee. Despite refusing, and telling him she “believed that type of meeting would be seen as inappropriate and did not think it was a good idea,” Weinstein “asked her out approximately 15 more times.” She attempted to avoid contact, the report read, “but he would use his secretary’s telephone extension to disguise the origin of the call.” She notified her supervisor about Weinstein’s behavior.

A woman who worked on Weinstein’s direct staff told investigators that on more than one occasion he touched her and made her feel uncomfortable. Once, he hugged her five times within 30 minutes, “front to front with his body touching hers from shoulder to hip.”

She said Weinstein “makes it a practice to read poetry to her and other females at [the National Archives] after working hours with the doors closed.”

She was working the evening Weinstein assaulted Trautman. She “thought that it was very odd that when she knocked on Weinstein’s door… that he did not behave in his usual manner, i.e., to call out and tell her to come into his office. Instead, Weinstein came to the door and opened it himself. She said she went to his door on two occasions during the time Trautman visited and on both occasions Weinstein opened the door.”

An FBI memorandum noted that, “The alleged victims expressed that they endured Weinstein’s harassment because of his position as the Archivist.”

The final Report of Investigation summarized the findings:

<p><em>The OIG substantiated that WEINSTEIN assaulted a [National Archives] female employee when he kissed her without her consent while she visited him in his office after [National Archives] business hours. The OIG substantiated that WEINSTEIN violated Title VII, Civil Rights Act: Sexual Harassment, and[National Archives] policies and procedures when WEINSTEIN created an offensive work atmosphere by having verbal and physical conduct of a sexual nature that exceeded generally accepted standards of office decorum when he invited female employees to his office after hours, touched them without consent, and continuously requested subordinate female employees to meet and socialize with him after hours despite repeated refusals.</em></p>

Before the investigation closed, the White House Counsel’s Office, which at the time was led by Fred F. Fielding, met with Weinstein’s attorneys. Already, the issue of Weinstein’s medication had been raised as a defense for his conduct.

A longtime Washington attorney, Fielding served in the Nixon and Reagan White Houses, and had known Weinstein for more than 20 years. In 1986, they co-wrote the joint statement released by the U.S. delegation that monitored the presidential election in the Philippines. One of Fielding’s first official acts upon returning as White House counsel in 2007 was to meet with Weinstein during the missing Bush email investigation.

The Report of Investigation shows that either Fielding or someone from his office sent a message to the Public Integrity Section, through Weinstein’s attorney, that they should allow Weinstein to submit information to become part of the official file, and should share the OIG draft Report of Investigation with Weinstein’s attorney. The plan was to then have the White House review the report, the records show, “and respond after this process.”

It was an extraordinary suggestion.

“The White House Counsel’s Office interfering in an agency OIG investigation is completely inappropriate, and undermines the independence of the inspector general,” said a former federal inspector general who had no involvement with or knowledge of the case prior to being contacted for this article, and who asked for anonymity to share candid views. “I would never share the draft Report of Investigation with a subject’s counsel, nor allow them to add information to the report. And I would present the report to the prosecutor, not to the White House, even if the subject was the head of a Cabinet or independent agency.”

It is unclear from records and notes if Weinstein’s team ultimately saw the draft. But the opportunity to do so underscored what the former federal IG called the “political sensitivity” of the case.

In early August, soon after Fielding’s office intervened with investigators, Public Integrity Chief Welch declined to move forward on the case, due to “insufficient evidence.”

Fielding, now a partner at the law firm Morgan, Lewis & Bockius, did not respond to repeated requests for an interview.

By that point, Weinstein had already offered to resign. But it would be four more months before he did.

Experts were baffled. “This case was more thoroughly investigated and vetted than almost any other sexual assault and harassment case I’ve heard of in more than 30 years,” said Carol E. Tracy, of the Women’s Law Project. “The response should have been at least an immediate resignation. It took entirely too long to get him out of that position.”

When asked why the case ended without prosecution, Brachfeld said, “I presented the Department of Justice with a good, tight case. What they decided to do with it after that was up to them.”

Welch declined to comment for this article. But experts dispute the notion that Weinstein’s resignation was an acceptable resolution to the substantiated allegations. “You can’t just allow an offender to move on down the road and think the problem will be solved,” said John Clune, a former criminal prosecutor and current plaintiff’s attorney specializing in campus rape cases and Title IX matters. “Sexual predators have a higher risk to reoffend if they don’t take responsibility for what they did.”

And that’s exactly what happened.

In January 2009, the iSchool at the University of Maryland—which has close, longstanding ties with the Archives—announced Weinstein’s appointment with great fanfare. In a statement at the time, then-President C.D. Mote, Jr., said: “The university is privileged and excited to have Professor Allen Weinstein joining our faculty. Allen’s breadth of experiences and remarkable vision are great assets to our campus.”

Representatives for Mote, who is now president of the National Academy of Engineering, said that he was not available for comment.

According to Trautman, the iSchool was told about Weinstein’s behavior in advance of his hiring.

Soon after Weinstein left the Archives, a young Archives employee who alleged being assaulted by Weinstein told Trautman that she had contacted officials at the University of Maryland in order to warn them about what he did to her. Trautman does not recall her name.

Whether the university took any action in response to the warning is unclear. Weinstein taught there for another 18 months. Two University of Maryland employees—one of whom had direct knowledge of the process that resulted in his ouster from the school—were granted anonymity to give accounts of what they know.

The first university employee said that in the spring of 2010, Weinstein sexually assaulted a graduate student. “He asked the student to bring materials to work on to his home,” the employee said. “After she arrived, he began speaking in a sexually suggestive manner. Weinstein then grabbed her and kissed her. She later worried she might be partially responsible, but only because she had agreed to bring the work materials to him. She was horrified and needed to tell someone, but didn’t want anything to come of it.”

The second university employee said, “The student told me that Weinstein grabbed her, kissed her, and stuck his tongue down her throat. She was seriously considering leaving the program after that.” It is unclear whether the employees were talking about two separate students or the same individual.

The first employee said that about two weeks after the student reported the assault, the University of Maryland fired Weinstein following a brief, secretive legal process.

When interviewed in February 2016, then-interim dean of the iSchool, Brian Butler, said that while he didn’t have firsthand knowledge, he understood Weinstein had left the university for health reasons. In a subsequent email, Butler wrote, “The goal of the appointment was for him to organize and lead events and teach seminars. He did some of this during the 2009-2010 year... However, upon review, it was mutually agreed that continuing that appointment was not the best fit with his interests or the needs of the college’s programs, so the appointment ended.”

The University of Maryland declined repeated requests for interviews with President Wallace Loh and other officials for this article, but university spokesperson Katie Lawson wrote in an email, “Allen Weinstein was terminated from this university in 2010. Due to the confidential nature of personnel records, we cannot provide further detail.”

Allen Weinstein died of pneumonia in a Gaithersburg, Maryland, nursing home on June 18, 2015. His successor, David Ferriero—who, a National Archives source confirmed, knew the real reason Weinstein had resigned—warmly memorialized him on the Archives’ website, writing, “[We] will forever remember with gratitude his dedication to the mission and employees of the National Archives.”

Weinstein’s family and friends held his well-attended memorial service on a hot July afternoon on the gently sloping lawn in front of President Lincoln’s Cottage, on the grounds of the Armed Forces Retirement Home in Washington, D.C. Former Sen. Lugar gave a eulogy. Peter Kelly spoke about his old friend, and sang, “Danny Boy.” Timothy Naftali, whom Weinstein had named as the first federal director of the Richard Nixon Presidential Library, also delivered a eulogy.

“I am appalled by these revelations and my heart goes out to Allen’s victims,” Naftali said, upon learning the details of Weinstein’s misconduct during an interview for this article. “The portrait that is emerging is incompatible with the man, friend, and boss that I thought I knew.”

Weinstein’s official portrait, unveiled in a small ceremony shortly after he resigned, hangs in the east stairwell of the National Archives Building, not far from the Archivist’s office.

It was in February 2016, when first contacted for this article, that Trautman decided to speak publicly. “I knew then there had to be other women, and I had to stop it,” she said. “He’s gone, but this happens every day to women in the federal government. I hope by talking about it openly now I can help stop that, too.”

Later, Trautman wrote in an email, “Thank you for the call today—I felt like the Flor de la Mar unearthed from the depth. Forgotten and ignored in retirement as I was when employed by the National Archives. I felt that I was as forgotten as that ship.”

Anthony Clark is a freelance writer and former senior congressional staffer and speechwriter. Previously, he has written about the politics of federal presidential libraries, which are administered by the National Archives. This article does not necessarily reflect his employer’s views.

The records referenced in this article were released as the result of FOIA and Privacy Act requests, and a lawsuit, filed pro-bono on behalf of Ms. Trautman and Mr. Clark by Bradley Moss and Mark Zaid, of the law office of Mark S. Zaid.