Not all notable architects are demanding divas or money-sucking leeches.

Some, like Shigeru Ban, use their trained eye and elite status to aid humanitarian efforts in lieu of status-seeking trophy projects.

And he could be the man who re-shapes Nepal.

The Japanese architect recently announced he would be building emergency shelters to aid the displaced victims after two major earthquakes left more than 8,500 dead and tens of thousands homeless.

It’s not the first time he’s come to the rescue. Ban has given relief to Japan, Rwanda, India, Sri Lanka, and numerous other countries through the world, by using unconventional materials like cardboard and paper tubes to create temporary homes, churches, and even performances halls as cities work to stabilize.

These structures, along with mesmerizing museums and high-priced homes, contributed to his selection as the 2014 Pritzker Prize laureate—architecture’s highest honor.

It forced the architectural world to take Ban’s unexpected use of paper seriously.

“Through excellent design, in response to pressing challenges, Shigeru Ban has expanded the role of the profession; he has made a place at the table for architects to participate in the dialogue with governments and public agencies, philanthropists, and the affected communities,” the Pritzker jury stated during their announcement. “His sense of responsibility and positive action to create architecture of quality to serve society’s needs, combined with his original approach to these humanitarian challenges, make this year’s winner an exemplary professional.”

In 1994, Ban’s first project proposal—a series of shelter tents in Rwanda—quickly spawned a trend for the eco-friendly architect.

When displaced citizens began selling the metal poles supplied by the United Nations and using local trees instead, he proposed the use of thick paper tubes secured by plastic connectors. They were cheap and efficient and prevented any further critical deforestation of the area.

At $50 a pop, they also became one of the “cheapest collection” pieces at the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, Germany.

The Swiss furniture company collects and produces the works of some of the world’s most famous—and most expensive—designers. Frank Gehry, who built The Daily Beast’s home office, and Renzo Piano, who designed the new Whitney Museum, are also featured on site.

Most likely, these types of structures—or his less private “Paper Partition System”—will come in the first wave of relief to Nepal, followed by more advanced designs like his complex “Paper Log Houses,” which were first constructed in Japan in 1995.

A 6.8 magnitude earthquake that left the city of Kobe—then home to 1.5 million—with $100 billion worth of damage.

Paper tubes and local resources were used to create sizeable log cabin-like structures atop beer crates and sandbags. Being both cheap and quick to assemble, the design allowed more ambitious community structures, such as a Paper Church, to be constructed--and that’s the aim for Nepal, according to Ban’s relief organization, Voluntary Architects’ Network (VAN).

“In a transitional phase after a few months, we plan to supply temporary houses using local materials which are available in Nepal,” VAN stated on their website.

While locals work to rebuild their own homes, the team will also construct stronger, more culturally appropriate buildings for the community while aiding those who are financially unable to provide for themselves.

Some of Ban’s most glorious designs were temporary-to-permanent structures made in the wake of tragedy.

“Cardboard Cathedral” is his most dramatic.

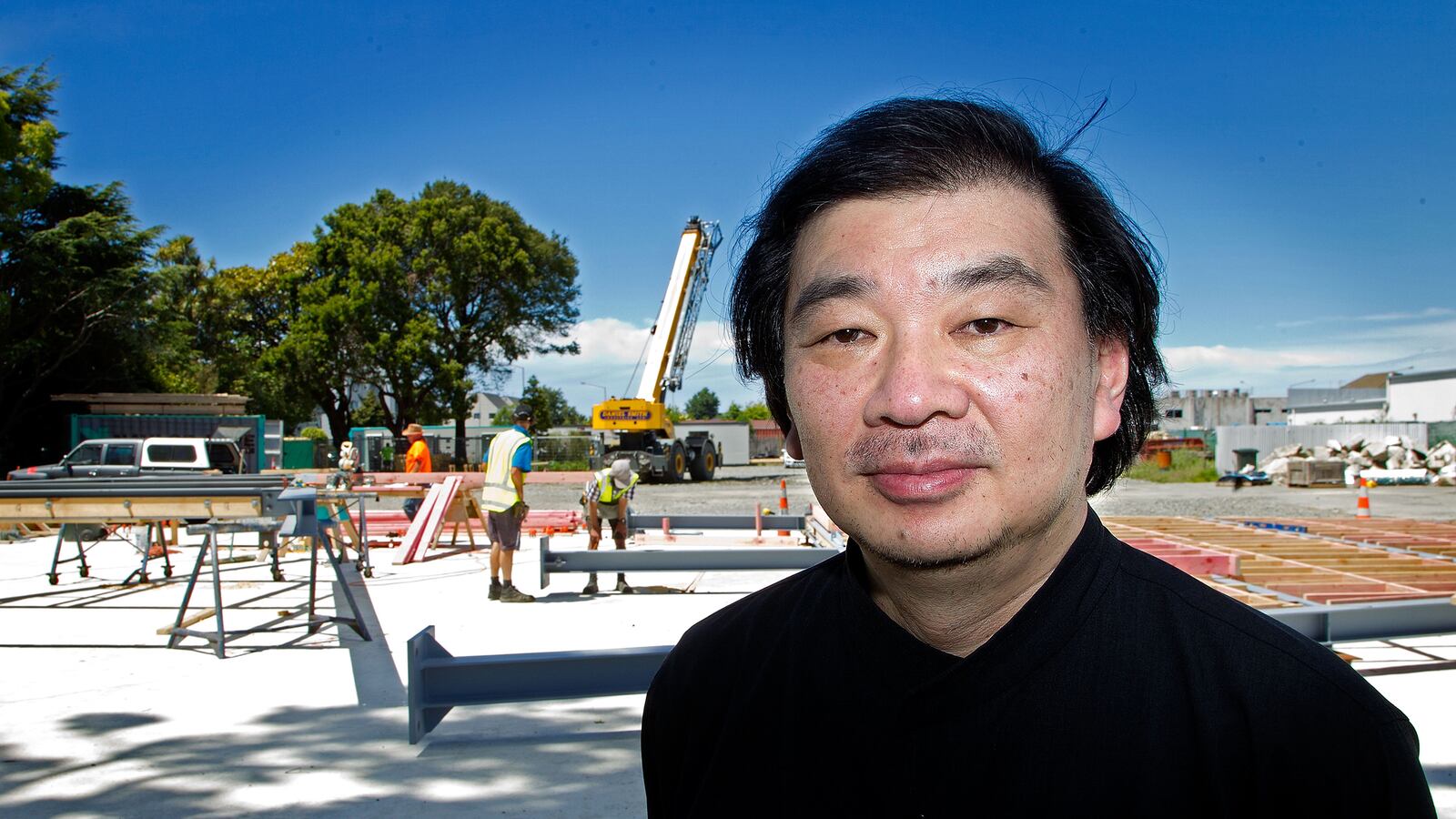

The structure, erected after a 6.3 magnitude earthquake devastated Christchurch, New Zealand, in 2013, used Ban’s cardboard blueprint to create a massive, A-shaped cathedral.

Multiple translucent triangles of different colors decorated the entire front of the structure, resembling a contemporary version of a tradition stained-glass motif.

For many of the city’s citizens, it’s considered the most important building in recent decades. “Internationally it is the most recognized building in the country,” Andrew Barrie, professor of architecture at Auckland University, told The Guardian shortly after it opened.

Ban has also designed a paper dome church in Taiwan, a temporary elementary school in China, and a paper concert hall in Italy.

Ban will face an extremely challenging physical context within which to work in Nepal.

The cultural loss within the country and the surrounding area, which is home to seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites, was devastating.

One of those historical sites, Swayambhunath—or the Monkey Temple—is a Buddhist complex that probably suffered some of the worst damage. As one of the oldest and most sacred pilgrimage sites for both Buddhist and Hindus, those sifting through the rubble are making sure to handle every brick with care.

They hope to preserve as many of the relics as possible even though they know it will be almost impossible to rebuild the original complex.

Architecturally admired Patan Durbar Square is another World Heritage Site devastated by destruction. Founded in the third century as an ancient royal palace, it was almost completely leveled as temples collapsed into piles of wood planks and jagged bricks.

UNESCO-sponsored experts are working to collect all historically significant items from all of the structures, which have relatively disappeared. They are working to protect them from looters and keep them culturally preserved.

While it’s uncertain what Ban’s work could mean for Nepal, his reputation means we can expect, at least, a temporary reshaping of the landmarks and a potentially new architectural landscape.