Many sportswriters are suggesting the Los Angeles Clippers’ players and coaching staff go on strike and not participate in the playoff series against the Golden State Warriors in order to protest team owner Donald Sterling’s racist remarks published for the world to hear this weekend. Instead, the Clippers showed their disdain for their owner by wearing their warm up shirts inside out before Sunday’s game.

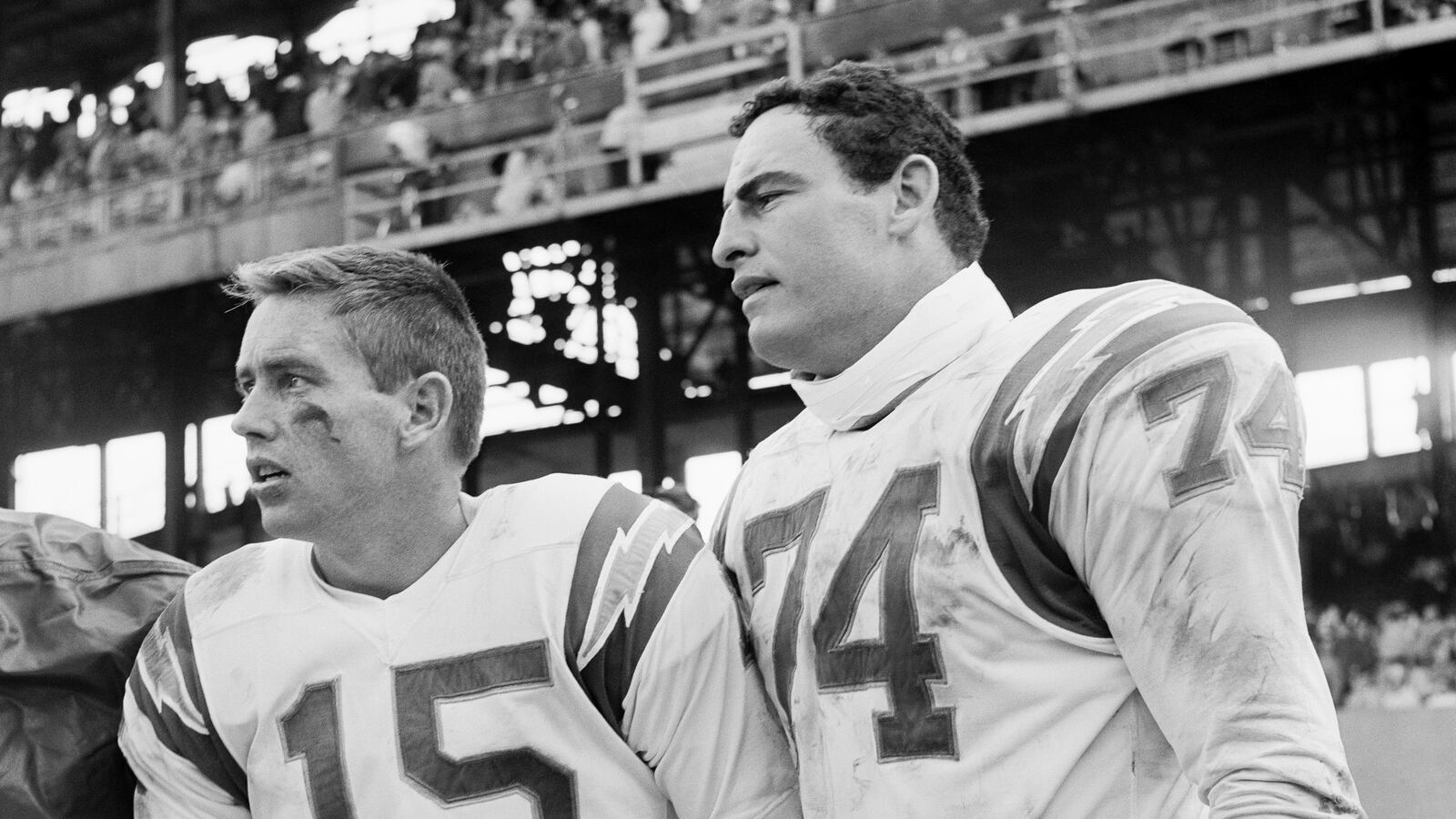

It is easy for others to suggest a boycott, but most of those advocates have never been in Ron Mix's position. In December 1964, Mix was selected for the American Football League All-Star team in a game that was to be played on January 15, 1965 in New Orleans.

Except the game was never played. Mix and his fellow players refused to participate.

The game was moved from New Orleans to Houston at the last minute because 22 African-American players didn’t like being refused service from taxicab drivers, hotel employees, and restaurants who obeyed Jim Crow.

Mix sees a fool in Donald Sterling, not Jim Crow.

“Donald Sterling, candidly, he sounded like a pathetic senile old man, but that doesn’t make it less despicable,” said Mix. “If I was to design a boycott, I would ask the fans to boycott, the empty seat would show the players there is someone who supports their cause and have a financial impact.”

Players had no alternative but to strike in 1965, Mix said.

“We were aware that New Orleans was hosting the game to demonstrate to the American Football League and the National Football League they [New Orleans] could support a football franchise. The last thing we wanted to do was assisted them in demonstrating they could support a franchise. … A boycott was the only alternative for the players."

Mix was treated well in New Orleans, but his African-American teammates weren’t. New Orleans leaders said the city was going to welcome the AFL All-Stars, which included 22 black players, with open arms. Segregation and Jim Crow were just ending, and the city desperately wanted a professional team. The American Football League was the only league at the time to truly embrace the African-American athlete as an equal on the field with white players. Major League Baseball struggled with integration, even through the 1960s. And the NFL’s Washington Redskins did not employ a black player until 1962.

“One of the things we [the AFL] needed was the unity of the white and black players for our new league,” said Abner Haynes, a former Kansas City Chiefs running back. Haynes had been a civil rights pioneer as one of the first two African-Americans to play college football in Texas in 1956.

“When the white players, Jack Kemp, Jerry Mays, who was our [Kansas City] defensive leader, and four or five other guys heard about what was happening, their character showed and my teammates were looking after me.”

The idea of a boycott of New Orleans didn’t take shape until the players met at the Roosevelt Hotel and started sharing stories. Neither Haynes nor Daniels was able to hail a cab at the airport to take them down to the city. They waited for about two hours before someone finally picked them up and took them to the hotel. Once they got there, things didn’t get much better.

“They had a woman operating the elevator and she said, ‘You monkeys come on in and get to the back.’ Finally we had about 10 or 12 guys in my room, we were talking sensibly. We were going to stay together. This was just another test,” he said.

The thought of a boycott of the game came up, and the discussion quickly grew serious, with Buffalo’s Cookie Gilchrest being one of the most vocal leaders.

“We were disrespected as men,” Haynes remembered. “We were not here because of color; we were here because of talent. Why should we go out there and put our lives on the line for people who don’t appreciate us? We were not appreciated here. Everyone agreed, you should not put your life on the line in that type of situation.”

The players acted alone and took a stand. They got support from their white teammates, including Jack Kemp, the Buffalo quarterback who headed the American Football League Players Association. Kemp, Mix, and the other white players put their careers on the line, as did the African-American players. They could have all been fired for their actions.

“We had no leverage,” Haynes said. “We weren’t playing for money, but we were playing for progress. Football players took the lead. Places like Atlanta, New Orleans, [and] Miami were death holes. Dave Grayson couldn’t get a drink at the bar. Our white teammates [in New Orleans] were there for us.”

Haynes did not know at the time that Houston Oilers owner Bud Adams was in contact with some of the players and offered an alternative site for the game: Houston.

“It was amazing the league moved the game. Stuff like that didn’t happen,” Haynes said.

Haynes did say he thought all the players were “kind of marked,” but none of them were blackballed.

The court of public opinion has begun to come down on Sterling as he has lost some marketing partners, but the Clippers coaches and players are keeping their next option close to the vest. NBA Commissioner Adam Silver will make some sort of an announcement a few hours prior to the Clippers next playoff game, after that the players will decide how they plan to handle the Sterling racist and sexists remarks. The players probably despise Sterling but they are under contract to play. The public may have more of a say on Sterling’s future if they follow the marketing partners lead and bail on the octogenarian who has stained the NBA with his mouth.