Just off the I-10 in Grosse Tête, Louisiana, behind the bars of a 40-by-80-foot enclosure, lives a 550-pound Siberian tiger named Tony. Alongside 18-wheelers, gas and diesel pumps, a 24-hour Cajun restaurant, and a gift shop, 14-year-old Tony leads a mellow life as the Tiger Truck Stop’s main roadside attraction. But while Tony lounges and visitors gawk, signs posted around the stop by its owner, Michael Sandlin, decry “the evils of animal rights.”

“The problem is that the people behind this fight, the animal rights organizations, it is their agenda to obtain total animal liberation,” Sandlin tells me. “They are, in my opinion, participating in domestic terrorism here in the United States. It’s their agenda to give animals equal rights and the problem with that is that if animals have rights, you cannot own them anymore.” He tells me about the absurdity of the ASPCA, the Humane Society of the United States, and PETA. (“I personally like hamburgers and fried chicken, I like to have an occasional steak, and Tony the tiger absolutely depends on [slaughtered meat.]”) He warns that unless we stand up to these organizations and stop them and their “extremism,” they will continue to cost animal industries and the American people millions of dollars in legal fees.

“I think it’s time that we start throwing some of these people in jail,” he surmises.

But Sandlin’s grudge against animal rights organizations has less to do with their anti-slaughter principles (or those commercials featuring sad puppies where “some chick comes and sings ‘In the Arms of an Angel,’” as Sandlin describes them), and more to do with Tony. The Tiger Truck Stop’s feline mascot is at the center of a years-long litigation battle between the state of Louisiana, Sandlin’s truck stop, and the Animal Legal Defense Fund. Though Louisiana outlawed private possession of big cats in 2006 and the state’s 1st Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Sandlin’s permit for Tony was invalid in 2012, Sandlin refused to give up. He sought out the help of Republican state Senator Rick Ward III and, with his help, a bill making an exception for Tony was drafted, passed by the legislature and signed into law by Governor Bobby Jindal on Tuesday. The precedent this new law (Act 697) sets is alarming, according to its opponents.

“When you allow a private individual to co-opt a public institution to pass laws that favor them and only them, that’s really the height of political corruption,” says Matthew Liebman, lawyer for the Animal Legal Defense Fund. The ALDF, along withformer state Rep. Warren Triche Jr. (the original proposer of Louisiana’s big cat ban) are challenging the new law’s constitutionality and suing the state, Sandlin, and the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries to revoke Sandlin’s exhibitor license and get Tony relocated to a sanctuary in Colorado.

“I think at the most basic level, tigers just don’t belong in cages in parking lots, just a short distance from the highway, a short distance from diesel pumps and idling 18-wheelers,” Liebman continues. “They’ve tried to make the focus on his habitat, the square footage, whether there’s grass, whether there’s air conditioning, and all of that is largely beside the point because you still have a tiger in a cage in a truck stop … When you set that side-by-side with the offer that the cat sanctuary in Colorado has offered, it’s really no comparison.”

While the convoluted legal battle to decide his fate drags on, said tiger in a cage has blissfully continued chewing on tire swings, napping, and, occasionally, when it’s hot, eating popsicles. After thirteen and a half years, after all, this is all he knows.

***

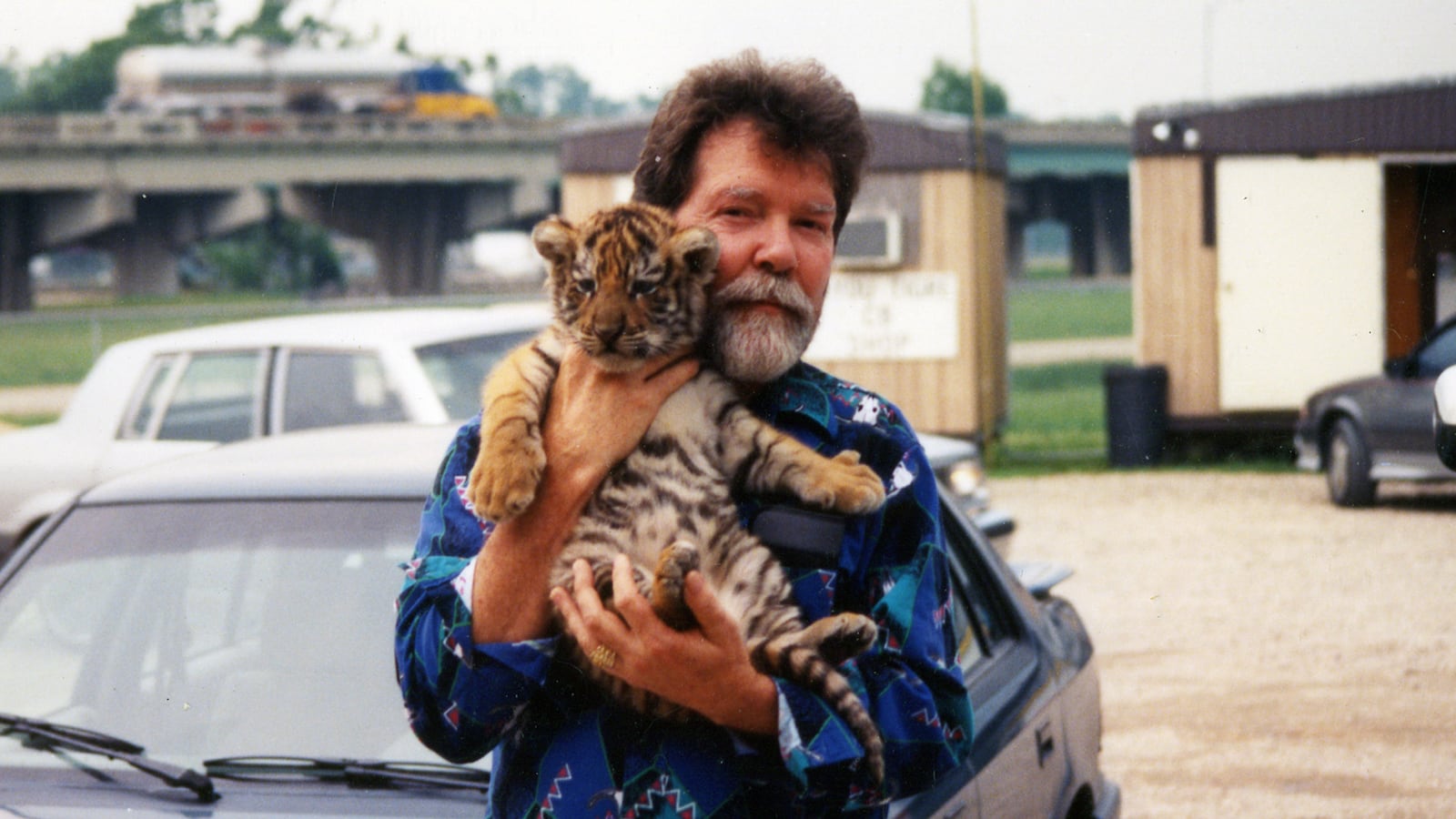

Tony the tiger was six months old when he came under Michael Sandlin’s care from a breeder in Texas. At the time, Tony was the youngest of four tigers exhibited at the truck stop: there was a white tigress named Salena, who became Tony’s mate, another named Rainbow, and a male tiger named Toby. Thirteen cubs were eventually born at the truck stop, though two were stillborn and another died at 10 months old (“They weren’t able to determine the cause of death,” Sandlin says.) The rest were sold to traveling animal acts in Florida, traded with other exotic big cat breeders, or given away. While Toby and Rainbow were eventually retired to a sanctuary, Tiger Haven, in Tennessee, Salena passed away of pancreatic cancer when she was three and a half.

Tony is the Tiger Truck Stop’s last cat standing, making him, of course, Sandlin’s bread and butter. The 2006 big cat ban prohibits Sandlin from acquiring any more tigers; Tony is only allowed to stay at the truck stop under the newly signed law because he has been continuously exhibited since before 2006. Though Sandlin says he and Senator Ward drafted the new law to apply as broadly as possible to other big cat owners with Class C exhibitor licenses from the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Department, a spokesman for the department confirmed that the new law actually only applies to Tony, as the other privately owned exotic cats were relocated to sanctuaries after the 2006 ban went into effect. (This forms the crux of Liebman’s and the ALDF’s unconstitutionality argument, as “when the legislature passes a law, it should have general applicability and not confer special favors on one person.”)

But how Sandlin, 51-year-old owner of a single truck stop, convinced an entire state legislature to pass a bill that goes directly against what that same legislature voted unanimously to ban eight years prior is, on the surface, baffling. Senator Ward, the sponsor of Act 697, did not return a request for comment but Sandlin, when discussing the bill, becomes passionate about not only Tony’s health and safety, but personal freedoms and the rights of small businesses.

Sandlin was born into the truck stop business; his father and grandfather built what was “the world’s largest truck stop” in Oklahoma City in the early ‘60s and owned a chain of truck stops in Texas called Tiger Energy. It was his brother, a Leo who always liked big cats, who first suggested getting real tigers as mascots. Sandlin’s father purchased the first two in Texas, Toby and Rainbow, but business dried up and the family eventually lost all their Texas locations. In 1987, with only $1000 to his name, Sandlin packed up the tigers, moved to Grosse Tete, Louisiana and took over what is now Tiger Truck Stop.

Today, the stop employs around 35 people, including several of Sandlin’s family members. Two people currently help clean Tony’s cage and feed him (he eats 10-20 pounds of horse and beef muscle meat every day)—though always under Sandlin’s direct supervision, he says. Tiger-themed video poker games abound at the truck stop, as well as tiger stuffed animals and T-shirts that read, “Animal activists taste like chicken,” available at the gift shop. Without Tony, the truck stop wouldn’t make much sense.

Not that that’s the only reason Tony must stay, Sandlin says. He maintains that Tony “enjoys” the people who come to see him and likes to lie on top of the enclosure and “watch all the happenings in the truck stop.”

“That’s sort of what bothered me the most when they say they want to remove him and send him to a private sanctuary is that a lot of the sanctuaries I’ve been to are preaching the gospel that these are wild animals and less human contact is better,” Sandlin says. “When you have these animals, most of which were hand-raised pets and accustomed to being petted or sweet-talked to, and [they are] either rehomed or taken from owners who loved and cared for them and all of a sudden they’re placed in these sanctuaries and they’re isolated and never petted again, I think that’s bad. It’s my opinion that if Tony was relocated to one of these sanctuaries, he would probably grieve himself to death.”

Sandlin’s concerns for Tony go beyond potential heartbreak, however. He describes the process of sedation that Tony would have to undergo to be moved to Colorado and why, at Tony’s age, it’s “even more dangerous” to attempt.

“I just happen to know that all the animals seized by the Department of Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries were dead within two months of being taken from their home,” he says. “There was no way that I was gonna stand by and let them come in and take Tony the tiger and have that happen to him.”

That last statistic, however, is a point of hot contention between both sides of the battle for Tony. Liebman calls it a “lie” that was frequently “parroted” by legislators on the floor of the state House and Senate. And Pat Craig, executive director of Colorado’s Wild Animal Sanctuary, the facility that has offered to take Tony in, also disputes it. “We have moved over 30 tigers in 34 years that were over the age of 14 and have never lost one due to anything associated with moving them,” Craig wrote in an email. “All of the tigers were much happier once they arrived here and began to realize the freedom and socialization they can have.” While listing the amenities that Tony would enjoy at the sanctuary, he includes a “much better diet, 20-acre habitats to roam freely and play with other tigers (yes, they actually like to be together and enjoy having friends), full time veterinary care, full time enrichment staff, and all the animals end up changing dramatically because they actually get to get out and exercise and have fun with each other.” He also adds that tigers typically live up to 23 years, “so [Tony’s] not old at all.”

For now, Tony’s not going anywhere. The Animal Legal Defense Fund is bracing for another years-long battle to “free” Tony (“Save Tony” is the slogan reserved for those who want Tony at the truck stop), a battle Sandlin equates to “fighting the American people.” His anti-animal activist stance doesn’t mean he supports the abuse of animals (he once took a hunter safety course that taught clean kills to cause the least amount of suffering possible) but he can’t see their efforts as anything but “nuts.”

“If you look at PETA’s website, it’ll say right up at the top, ‘Animals are not ours to eat, to wear, to use for entertainment, or to abuse in any other way,’” he says. “My comment would be, since when?”