There is no room for argument: Showtime’s provocative and gut-wrenching psychological thriller Homeland is the best new show of the season.

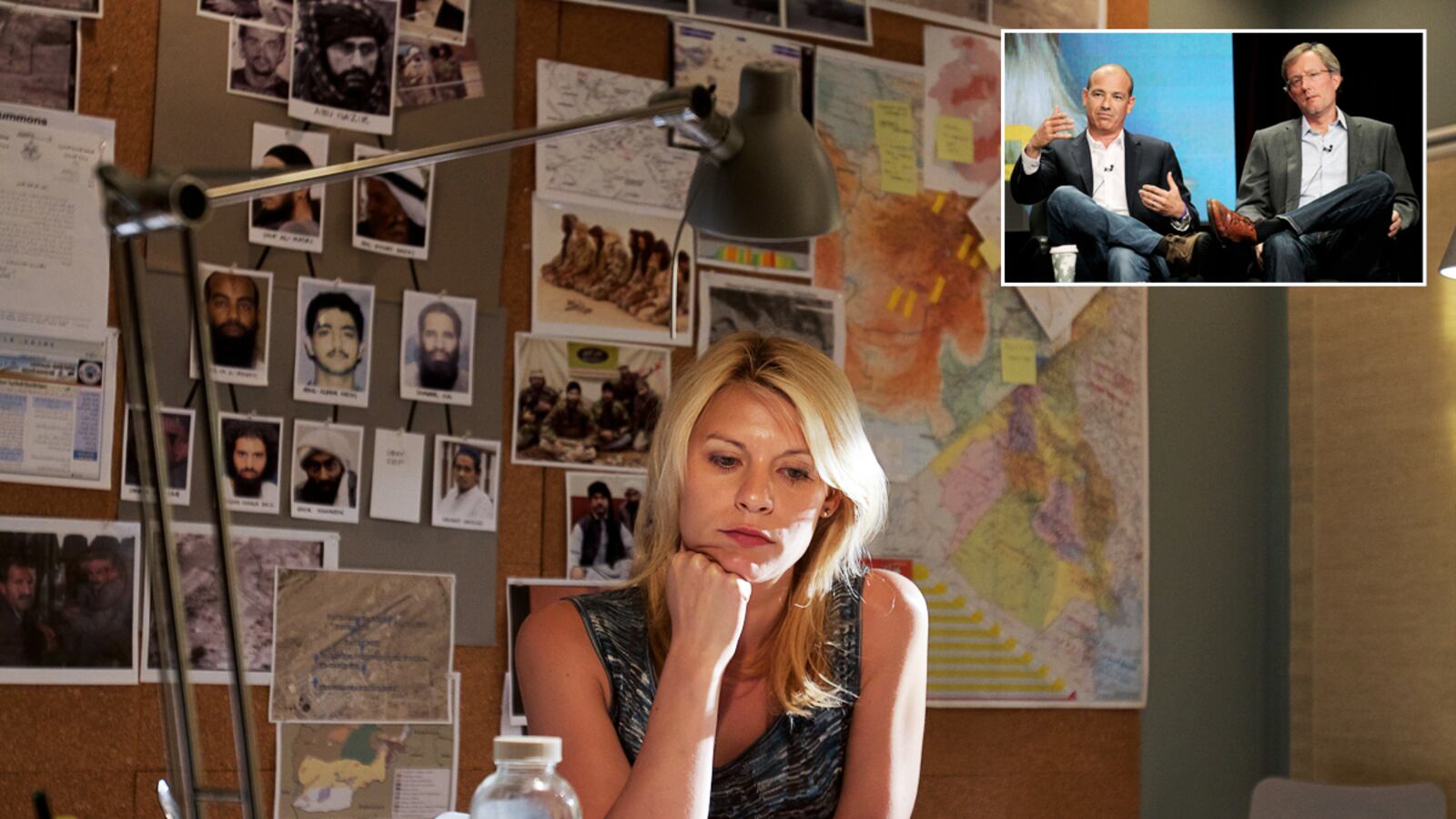

Revolving around two very unreliable narrators engaged in a series of riveting mind games, Homeland explores an America 10 years after 9/11, surveying the damage done to both the national psyche and the central protagonists. Claire Danes plays Carrie Mathison, a CIA operative with both a mental illness and a troubling sense of personal guilt that she missed crucial intelligence prior to the Sept. 11 attacks; Damian Lewis (Life) plays soldier Nicholas Brody, a prisoner of war who returns home to a family that long thought him dead, and who may or may not have been turned into an enemy of the state during his eight-year captivity in Iraq.

The ratings for Homeland (Sundays at 10 p.m.), which aired its seventh episode (out of 12) this week, have sharply increased since the show launched in early October; if you look at its average audience on all platforms (4.1 million total viewers), Homeland becomes Showtime’s most successful freshman show ever. Loosely based on the Israeli series Prisoners of War, Homeland has already been renewed for a second season, amid nearly universal critical acclaim. Unlike the source material, a family drama focusing on two POWs returning home after 17 years, Showtime’s version balances familial drama with a provocative psychological thriller, according to co-creator/executive producer Howard Gordon (24).

“Theirs is really a Rip Van Winkle story, a big and sometimes tragic, sometimes moving, story about these two returning POWs,” he said. “Ours is really a story about heroism and about the ‘war on terror,’ in quotes, because the war on terror is such a huge umbrella and under it includes our own wars in Iraq and Afghanistan [and] the war at home in terms of how we’re surveilling perceived threats and what we’re doing about them.”

The issue of surveillance is especially prominent within Homeland, which has Carrie watching Brody’s every move, even as the eyes of her superiors—particularly David Harewood’s sharp-edged David Estes, a former lover of Carrie’s, and Mandy Patinkin’s Saul Berenson, her grizzled mentor—are monitoring her as well. Add to that the idea that the audience is in fact watching her watching him, and there’s an intentionally uncomfortable sense of voyeurism, one that adds to the deep patina of paranoia that hovers uneasily over the entire piece.

“One of the ideas that we’re trying to explore is the idea of the surveillance state,” said showrunner Alex Gansa. “Someone’s got a GPS location on me; there are cameras in every mall and on street corners. You go to Times Square and chances are somebody’s watching you. The theme of voyeurism was very much at the center in our minds as we began to tell this story.”

It’s not the first time that television has sought to mine the conflict in the Middle East for story material. 24, FX’s short-lived Over There, the most recent season of Damages, and others have used the ongoing war on terror as a backdrop for character-centric drama. But Homeland arrives at a particular time, 10 years after the towers fell and just a few months after the death of Osama bin Laden, who seems echoed in the shadowy character of Abu Nazir (Navid Negahban), Brody’s captor.

“We were tremendously fortunate, in a way, with the synchronicity of the 10th anniversary of the towers coming down and then this collective sigh of relief that the country breathed after Osama bin Laden’s death,” Gansa said. “Whether that’s a justified sigh of relief or not, that’s open to debate. But there was such a sense that a victory had been achieved after a long period of time. The war-on-terror fatigue that has taken place between 9/11 and the death of bin Laden was mitigated somewhat by his death. That has allowed people to look at this area again with a fresh impetus of objectivity.”

Additionally, Homeland’s larger themes may be symbolic of 24’s legacy, but it isn’t a continuation of Fox’s global franchise, on which both Gordon and Gansa worked. Kiefer Sutherland’s Jack Bauer was largely an instrument of American vengeance, designed to combat the revelation of our innate vulnerability.

“Jack Bauer was very much an immediate response to the World Trade Center,” said Gansa. “It was a muscular, American response to that event. Ten years later, and the country has suffered in many ways, financially and psychologically. A soldier commits suicide every 80 minutes in America now. This is more of a psychological toll of the last 10 years of the war on terror, and the show reflects that. 24 was almost an action thriller … it was wish fulfillment, and this is more about trying to explore where the country is, where we are as a nation as we face these problems: keeping ourselves safe, being true to what America is, and how those things work in conflict and in concert with each other.”

To that end, the show has kept Brody’s presumed loyalties deliberately vague and depicted the new faces of extremism, whether that’s the dangerous Al Qaeda sleeper agent that Carrie suspects Brody to be or the blonde rich girl, American terrorist Aileen Morgan (Marin Ireland), caught up in a plot to take down her own country. In an act intended to reveal our own insecurities, producers depicted the ex-POW Brody as an Islamic convert, a fact revealed in the second episode when he engaged in ritualistic prayer in his garage, far away from the eyes of his wife, Jessica (Morena Baccarin). In the most recent episode, the audience’s perception of Brody’s conversion pivoted sharply when he sincerely explained to Danes’s Carrie that he had converted to survive years of imprisonment and torture, connecting with the spirituality at hand. (The King James Bible, he said, was nowhere to be found.)

“We wanted to, as much as possible, decouple the association between terrorism and Islam,” said Gordon. “When you see [Brody] praying, you realize that he has converted. It’s really about the audience bringing their own prejudices and their own assumptions to that fact. The idea of the so-called blue-eyed Islamist is one of the great fears of law-enforcement agencies, people who have been turned, whether in prisons or a misguided affinity for certain causes, or—in [Aileen’s] case—an overbearing father. We tried to imbue that with some psychological reality.”

Likewise, Gansa said that Lewis has been in fairly regular conversation with an imam in North Carolina in order to accurately depict Islamic rituals and to imbue Brody’s choice of doctrine as just that: a choice. “We don’t view it as a forced conversion; we view it as a conversion of necessity,” said Gansa. “That was a man who was beaten, tortured, isolated, reaching out to find some spiritual meaning in a world that makes no sense to him anymore, and what was available was this faith, which saved him and kept him alive for those years. It wasn’t a stepping-stone toward any terrorist behavior. It was a way of maintaining his sanity.”

And, said Gansa, a way for Brody to find some semblance of inner peace.

It’s a given that in any cat-and-mouse chase, eventually cat catches mouse or mouse escapes, so it raises the question: just how long can Homeland keep the Brody plot going organically? Time’s James Poniewozik recently questioned whether Homeland had a second season in it (Showtime’s executives clearly believes it does), but the central tension—whether Brody has or hasn’t been turned—will one day need to come to a head.

“Even after we went to pilot, there was a sense of ‘How long can you keep the Brody story going?’ and is the question of ‘Is he or is he not a terrorist?’ and ‘Has he or has he not been turned?’—is that enough to sustain even a season?” said Gansa. “As we got into the story room and started discussing it, it has expanded and bloomed in a way that clearly Brody is going to exist at least through the first two seasons.

“Beyond that, you have a franchise with Saul and Carrie and the CIA and their battle against terrorists,” he continued. “I think the series has legs. How long the Brody character exists in that narrative, I don’t know. But certainly for two seasons.”

Gordon agreed. “This is a show about the CIA,” he said. “In the end, there’s a CIA agent or several CIA agents, and that’s a very durable engine.”

In the meantime, Homeland has managed to attract the attention of viewers and critics alike, who revel in the serpentine twistiness of the plot and the ambiguity of the motivations of both Brody and Carrie, two deeply damaged individuals who seem to find a sense of something simpatico between them, an understanding and an attraction that goes beyond their unknown (and perhaps unknowable) objectives. The show delves into their home lives to paint a portrait of the way that war changes us, and that, as with Odysseus, coming home isn’t necessarily coming back to the life you left behind.

But, to borrow a parlance from Gansa and Gordon’s 24, there is an overwhelming sense of a ticking clock in the background, something that will only build as the tension mounts, and there’s every indication that Gansa and Gordon and their writing staff have cooked up a shocking season-finale cliffhanger that will make viewers insanely anxious for the second season.

“If we don’t,” said Gordon, “we haven’t done our job.”