Perhaps The British Museum’s latest exhibition, Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art should come with a warning: “Don’t try this at home.”

After all, in 1861 an anonymous source observed: “a foolish couple copy the Shunga spraining a wrist.” For this exhibition—which offers a crash course in the ceaseless and inventive intertwining of limbs in the most beautiful way possible—the museum has imposed an age limit of 16 to enter.

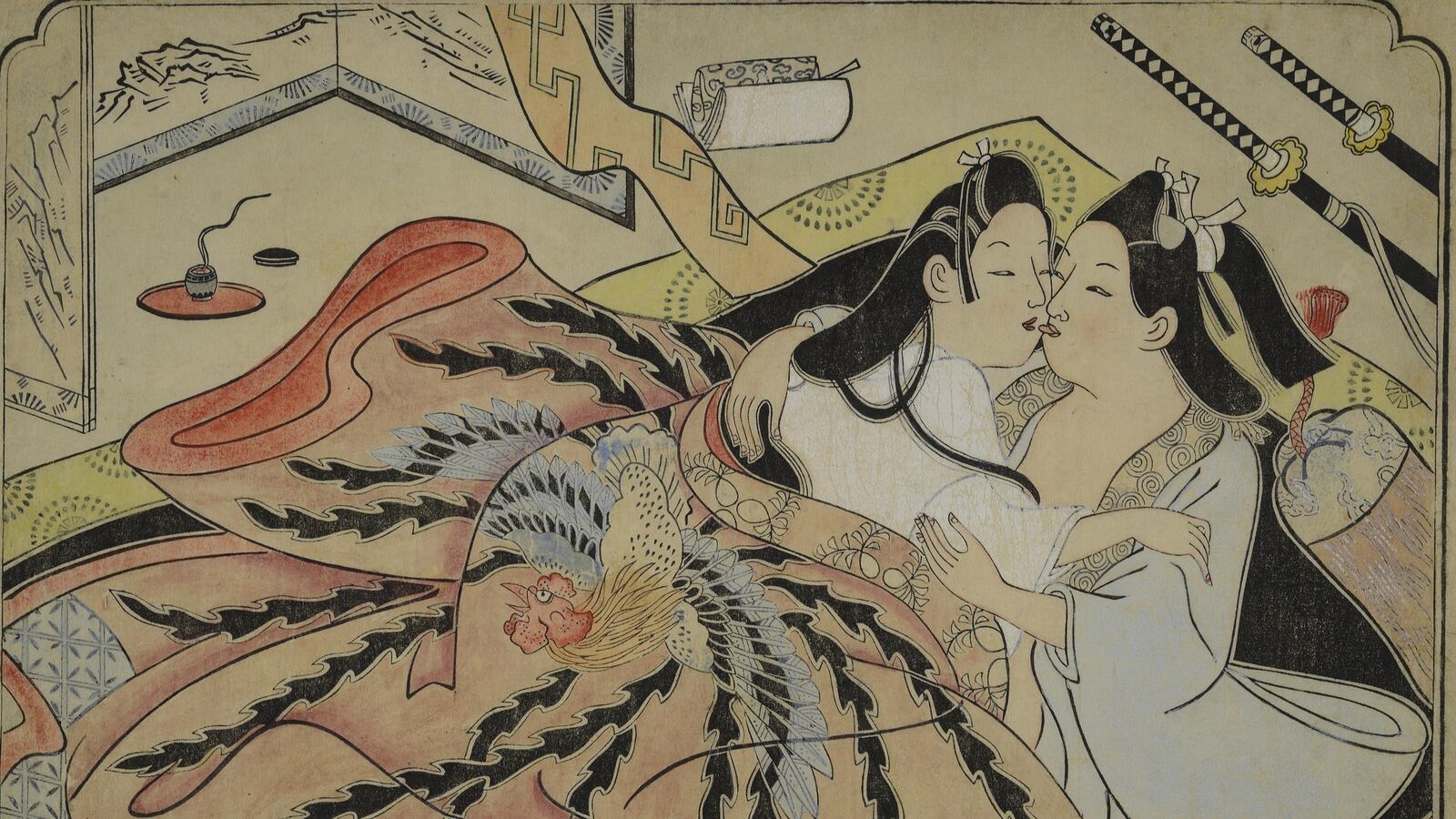

Shunga are beautifully crafted erotic paintings, woodblock prints, and books; they are rendered with powerful outlines and brought to life with colorful pigments. Translated loosely as ‘spring pictures’ or ‘pillow pictures,’ Shunga were produced in Japan between 1600 and 1900, partly as a form of sexual education. They’re eerily beautiful and also wickedly funny: Tsukioka Settei’s Shunga parody of an educational book for women, Great Pleasures for Women and their Treasure Boxes (c. 1755), shows a couple making love while taking a break from making noodles.

They are startling too: it’s not everyday that one sees a pair of octopuses taking their pleasure with a naked woman, as in Katsushika Hokusai’s Pine Seedlings on the First Rat Day (1814). Like the candid eroticism of their images of sex, and the frankly amorous looks exchanged between their depicted lovers, these artists were not bashful when it came to branding: Kawanabe Kyõsai’s seal, for example, takes the form of a vagina. The geisha who plucks at her shamisen while straddling her partner in Kitagawa Utamaro’s Picture Book: The Laughing Drinker (1803), is perched in a position that’s precarious to say the least.

As Timothy Clark, head of the Japanese Section at The British Museum and curator of the exhibition says, “Birds do it, bees do it, we may live to see machines do it…certainly now everyone in the country knows that octopuses do it!”

Shunga is a celebration of sexual pleasure. Though some of the poke-out-your-eye-with-a-penis positions seem a little perilous, the practitioners of Shunga are surely satisfied. “If I don’t do it even for half a day, I lose my appetite,” says a man in the fourth month of Katsukawa Shunchõ’s Erotic Illustrations for the Twelve Months (c. 1788)—as he has sex for the ninth time that day.

But are Shunga realistic enough to be educational? The exaggerated size of the genitals of the promiscuous participants certainly wouldn’t suggest so. The Album of Flowers and Moon (1836) with its bizarrely innocent title displays an amusing penis-measuring scene; the first half of Abbot Toba’s scroll, more appropriately titled Pictures of Contests (1400s), shows a phallic contest in which court officials measure the penis sizes of naked men. As one of Toba’s disciples commented, “If it were depicted the actual size there would be nothing of interest.” Shunga are eerily beautiful—but they’re also grotesque: the second half of Toba’s scroll tells the story of a merry ‘fart battle.’

So, why weren’t Shunga accepted with playful goodwill in the West? According to Clarke, in early modern Europe, eroticism was relegated to genres of mythology painting and the nude, while in Japan, lovemaking was thought to derive from the Japanese gods of creation. As he puts it: “Cosmic sex formed Japan!”

Shunga showcase sex between different classes, ages, and occupations: they promote sex between loving married couples, daring young lovers, and guilty cheating spouses. At the exhibition, you’ll see mature Buddhist priests engaged in sexual intercourse with their adolescent trainees, an imperial princess making passionate love to her warrior bodyguard in the palace grounds, a salesman being set upon by six lusty women, and a client interrupting a geisha’s performance to claim her as his lover.

And that’s not all you’ll see. Shunga’s imaginative couplings know no bounds: They involve crossing boundaries between species. There’s the peeping frog in Suzuki Harunobu’s Woman Stepping into a Bath (late 1760s), and the pair of mating cats being gawked at by the couple making love in Utagawa Kunisada’s Deep Feelings of Birds and Flowers, Genji of the East (c 1837).

As Neil MacGregor, director of The British Museum, says, “The Japanese paint the pleasures of sex like nobody else.” Shunga is the solution to the “lack of archaeological material” and the “little material traces” that tell us how different cultures performed sex, and whether they enjoyed it.

And, somehow, Shunga are surprisingly discreet. Although these images showcase overt sexual encounters, their participants cling onto their clothes. In fact, clothing cleverly emphasises the sexiness of the act. Kitagawa Utamaro conveys the intimacy of a couple’s lovemaking in a scene from Poem of the Pillow (1788) by providing a glimpse of their entwined legs through the man’s silk jacket; in Needlework (1794-5), he inserts a subtle sense of eroticism into an otherwise everyday scene by dressing his models in loosely worn clothes and offsetting the flash of a white leg against a bright red undergarment. Artists skilfully modulate the patterns on their models’s robes to suggest the beautiful curving bodies beneath; they use fabrics to adorn and frame the body.

A combination of art and sex is at the heart of Shunga, and any exhibition that seeks to explore the relationship between the two is bound to cause a stir. Clark describes Shunga as “a kind of love letter to sex” (though he’s not sure his colleagues would agree with him.) After all, Japan’s answer to cheating on the husband with the postman was cheating on him with the book lender who distributed Shunga directly to people’s homes. A love letter indeed.

Shunga: sex and pleasure in Japanese art will be on display at The British Museu from 3 October 2013 until 5 January 2014.